By Laurie O’Neill — Correspondent

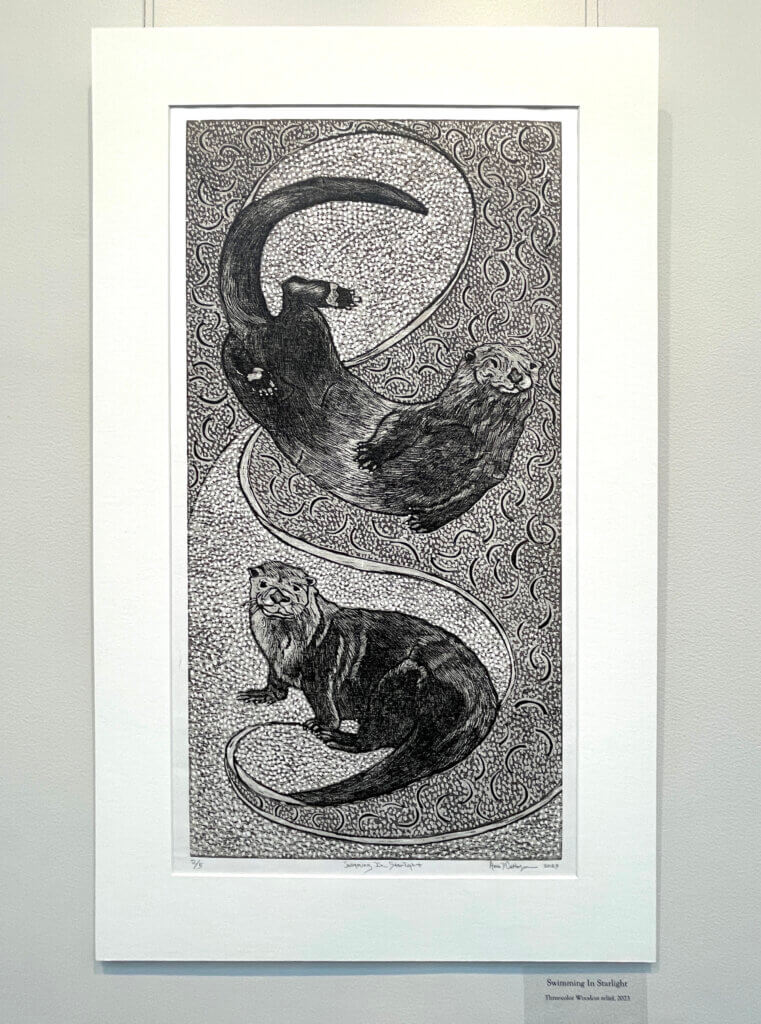

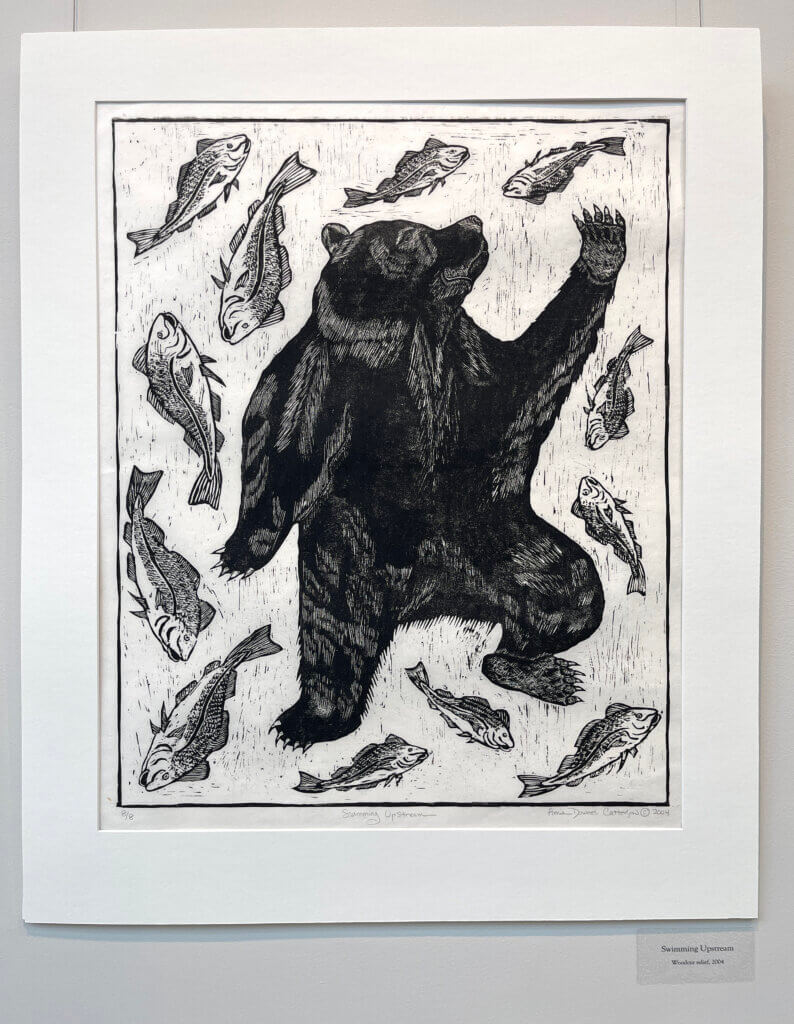

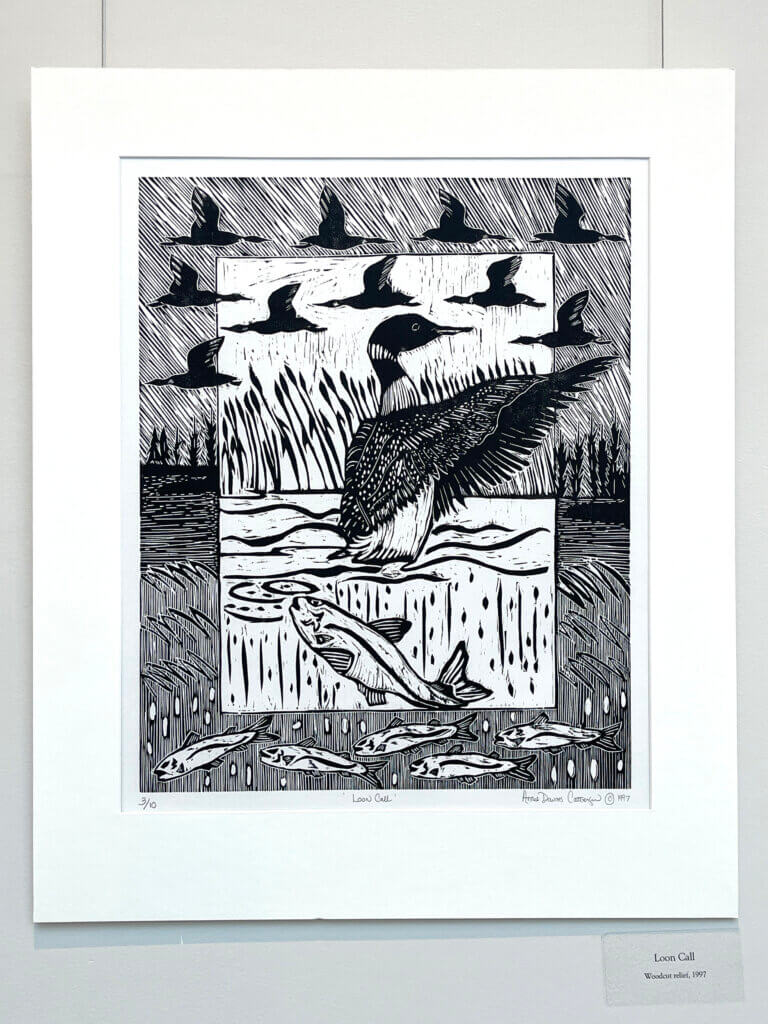

Annie Downes Catterson’s woodcut relief prints, mostly of animal totems — otters and coyotes, bears and birds — convey “whatever a viewer brings to them,” she says.

Catterson, however, doesn’t often ponder “how people respond to my work one way or the other. I try not to think of my audience,” she says.

Instead, the prints she has created for many years, some of them as illustrations for books, “I do for myself,” Catterson says.

Soft-spoken and thoughtful, she doesn’t mean to sound egotistical. “What I make is an aesthetic choice based on an internal narrative,” she says. “Viewers can take away what they wish.”

Catterson is the Main Library’s Munroe Artist of the Month in June, and her exhibit is titled “Swimming in Starlight and Other Stories.” It reflects her keen interest in Native American legends and indigenous art forms. Over the years, she has transcribed Cree Indian legends from the “meticulous” ethnographic notes, myths, and legends her father, P.G. Downes, collected in the 1930s.

A generational fascination

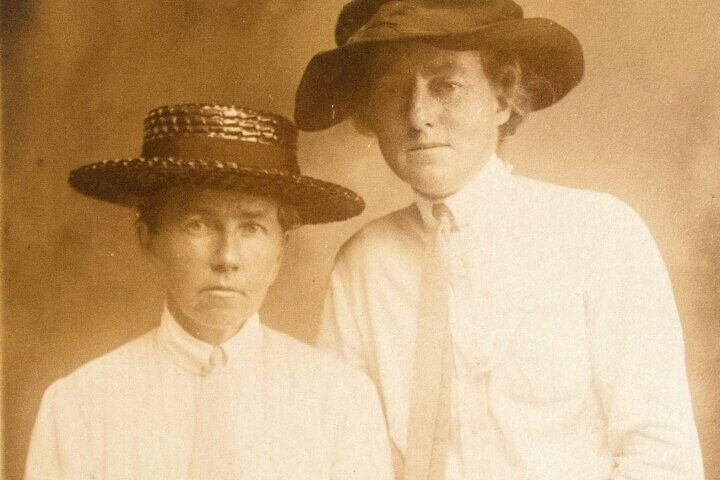

A Harvard graduate who taught at Belmont Hill School for many years, Downes was an ethnologist, cartographer, and naturalist. He traveled by canoe to explore the Great Barren Lands in Canada, where he learned the ways of the Cree and Dene people and acquired some of their language.

Catterson’s affinity for the natural world comes from her father and from her childhood in the Conantum section of Concord, where she spent endless hours investigating the woods and wetlands, fields, and rivers that were her backyard. In the early 1970s, she lived on a farm in Ohio.

Having earned a BFA at Massachusetts College of Art, Catterson received an MFA in printmaking from Ohio State University, where she had “a wonderful folklore teacher who really encouraged me,” she says. In 1982, she enrolled at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, where she lived on a Salish Indian reservation.

While there, she notes, “I found a comfortable affinity for the northwestern Canadian coastal region and renewed inspiration for my art.”

After earning an MEd from the University of Illinois at Chicago, Catterson began a career in education that included two years of teaching visual art at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, and 28 years at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools as an instructor in Studio Art.

Post-retirement, Catterson moved back to her family home, one of the original mid-century modern houses in Conantum, where she continues to create her prints. The artist also shares a workspace in Maynard.

A passion for printing

Woodcut relief printing is time-consuming and messy, Catterson says. In the process knives and gouges are used to carve an intricate design into the surface of a block of wood, leaving the printing parts level with the surface. Then the artist rolls ink onto the block and makes an impression, or print, of the design.

Catterson has a side passion: competitive dog training with her flat-coated retriever. It’s challenging but offers her “the social connections of being in the dog training world.”

She has illustrated four books of Cree Indian legends that she transcribed from her father’s notes. One of them, “The Story of Chakapas,” tells the tale of a mighty hunter who, after trapping all living creatures, proves his prowess by ensnaring the moon.

Though she works in several media, Catterson has focused predominantly on woodcut relief printing. She describes her artmaking practice as “having some kind of evocative personal narrative that I feel I have to get out. I need to be inspired, to feel a sense of urgency to create,” she says.

At once compelling and tender, the black and white or tri-color woodcut prints “comprise my ongoing exploration of the totemic qualities” of her animal subjects, Catterson says. Each piece evolves as she works: “I don’t pre-plan an image because once I start carving, it can change.”

Catterson produces about four prints a year. Each takes about three to four months to complete, and she can only concentrate on one task at a time. She is hesitant to speak about a work in progress, not wanting to “jinx it.”

One piece, which she kept talking about with an artist friend, she first tried as a print. She went through “a lot of wood,” then a monoprint, and then a drawing. “Every single one failed,” she says.

But many more succeeded. Viewers can see some of them in the “Swimming in Starlight and Other Stories” exhibit that runs through June 30 in the Munroe Gallery upstairs at the Main Library at 129 Main Street.