By Laurie O’Neill — Correspondent

This is a story about the founder of the Concord Art Centre, now called the Concord Art Association.

It’s also a story of the early 20th-century bond between two Concordians, one a golf champion and the other a much-admired artist.

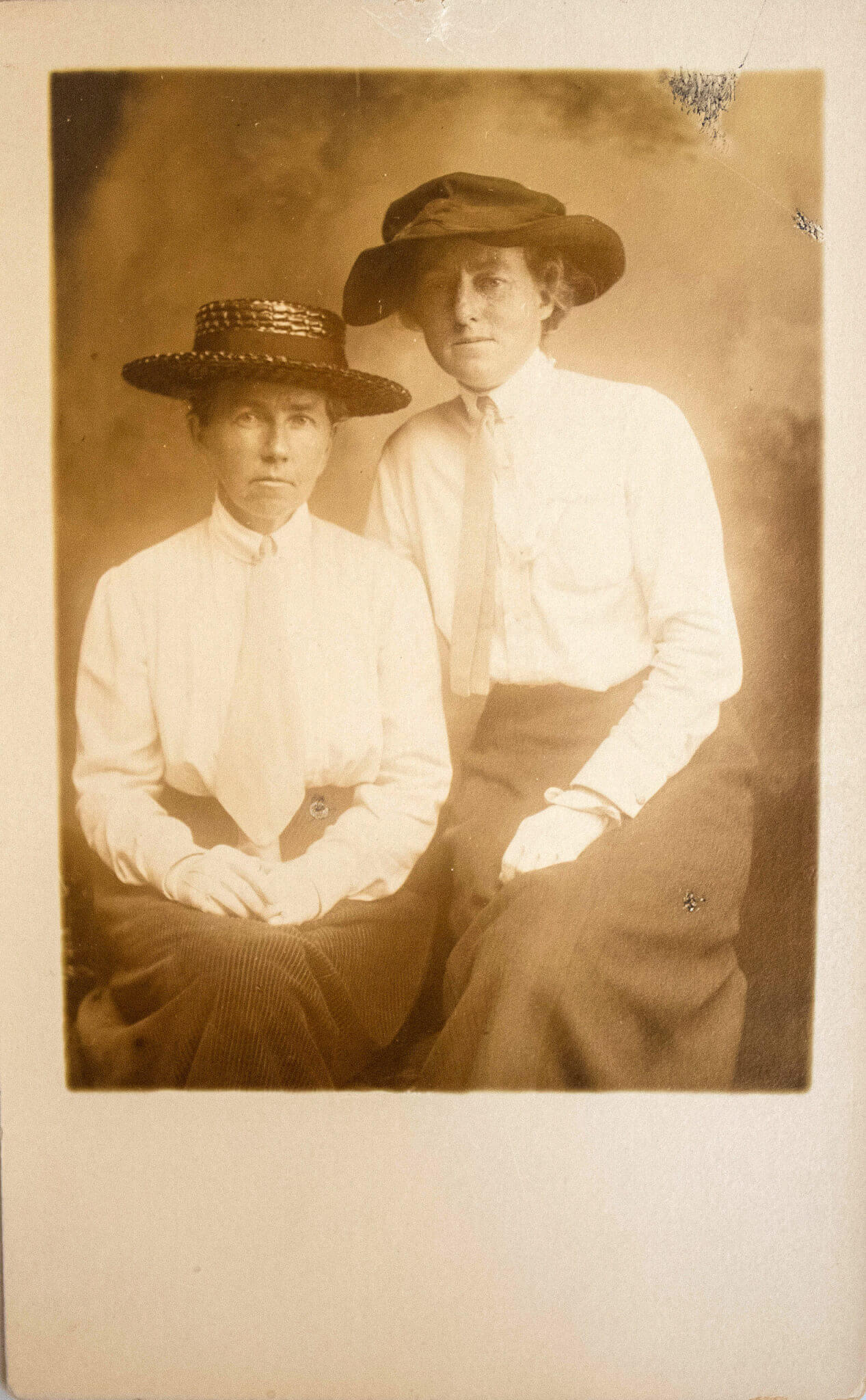

Grace Keyes and Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts were faithful companions for 27 years. They traveled the world, provided aid for soldiers fighting in World War I, and lived extraordinary lives.

They’re the subject of a June CAA exhibit titled “A Boston Marriage.” Sepia-toned photos and Roberts’ paintings offer visitors a glimpse into their life in Concord and beyond.

The women had an unconventional partnership for its time. The name for such an arrangement, “A Boston Marriage,” is associated with Henry James’ 1886 novel “The Bostonians,” even though James did not use the term. The novel dealt with the cohabitation of wealthy women, independent of male financial support.

Defying expectations

Roberts was the daughter of a Philadelphia steel baron father and a New York society mother. Keyes, a member of a Revolutionary War-era Concord family, was famous in her own right. A championship golfer at the Concord Country Club and throughout Massachusetts, she was also a founding member and a president of the Women’s Golf Association of Boston.

In 1900, the women met in New Hampshire, where Roberts was vacationing, and became instant friends. They purchased a farmhouse, which no longer stands, on Estabrook Road, not far from the Old North Bridge.

Roberts’ family had assumed that she would make her entrance into society, marry a wealthy man, and set up a traditional household. But longing to be an artist, she defied those expectations. At 15, she studied art in Philadelphia and later pursued her passion for painting in Paris and Rome.

Keyes was “a good organizer who could make things happen,” says Kate James, the CAA’s executive director. Keyes assisted Roberts, who worked in a studio behind their home, by planning the latter’s exhibits here and abroad and maintaining records of the sales of her work.

The women were known for their generosity and altruism, particularly during WWI. Roberts wanted to volunteer with the Red Cross, but her health issues would not permit it.

Instead, she created a series of ten paintings of Concord women who knitted mufflers, socks, and gloves and repaired clothing to donate to Belgian refugees in England.

Roberts sold each of the works for $1,000 and used the money to buy an ambulance and hire a driver to ferry wounded soldiers from Paris train stations to hospitals.

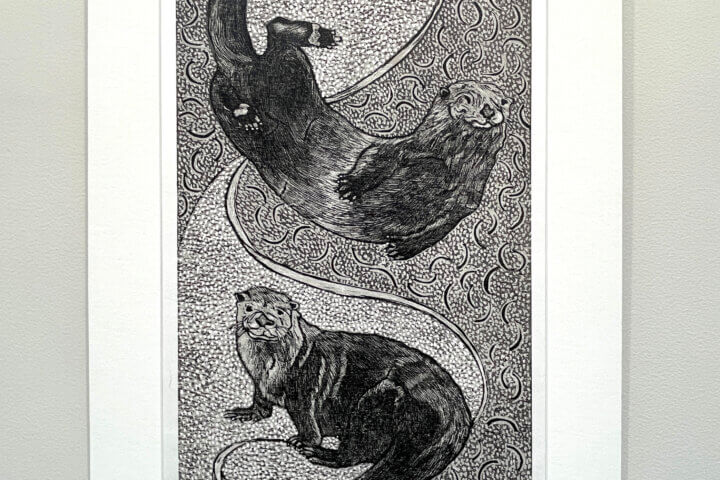

CAA permanent collection

Founding an arts center

Roberts had begun to install exhibits in locations around the town center in about 1915 to raise money for the war effort, support her fellow artists, and bring art and artists to Concord.

In 1922, she founded the Concord Art Centre and incorporated it as the Concord Art Association. Keyes was on the first board of directors, and Daniel Chester French, whose Minute Man statue stands at the Old North Bridge, was its president.

Roberts’ success as an artist allowed her to purchase the 1752 John Ball House at 37 Lexington Road and engage one of Massachusetts’ first professionally trained female architects, Lois Lilley Howe, to renovate the building. It became the Concord Art Centre.

The Centre displayed the work of Roberts’ contemporaries, including John Singer Sargent, Childe Hassam, Claude Monet, and Mary Cassatt, and it drew 5,000 visitors in its first summer. The CAA has occupied the building ever since.

Roberts’ 1919 oil “Concord (May),” which is in the CAA’s collection, is in the current exhibit and depicts a bucolic scene of the victory garden at her and Keyes’ home. “Memories of Antietam,” a painting for which Roberts is said to have sought Sargent’s assistance, spans an entire wall in the Town House. Another of her works, “On the Concord River,” is in The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

Roberts is said to have often commented, “I can paint as well as any man.”

“An incredible life”

CAA staff members, including Assistant Director Natalie Reiser and Director of Programs and Education Natalie Fondriest, went through old photo albums and other memorabilia to find images for the exhibit.

Keyes and Roberts “gave so much to Concord,” James says. “They had a loving home and an incredible life.”

The women were adventurous and fun-loving. They doted on their Pekinese named Chumwee, traveled widely, and once took a steamship down the Nile River with friends. They enjoyed spending time in Annisquam, a Gloucester waterfront village that figures in some of Roberts’ paintings.

But their time together would come to a tragic end.

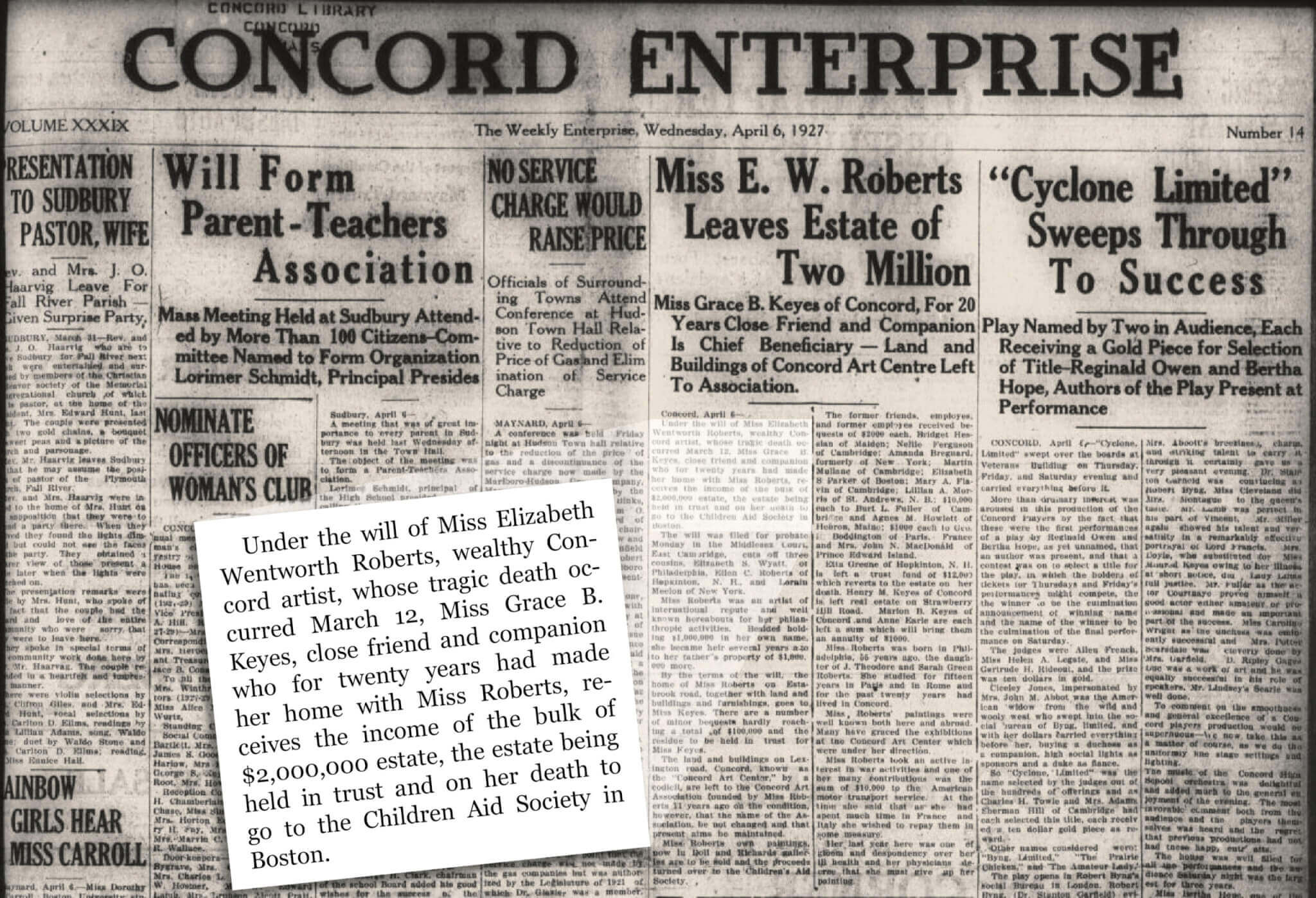

Following an illness, Roberts underwent surgery, after which her doctors advised her to stop painting. Suffering from persistent depression that was termed “melancholia” at the time, she took her own life in 1927. She was 55.

Roberts bequeathed her estate of $2 million — roughly equivalent to $36 million today — in a trust for Keyes and made sure the latter would have everything she needed for the rest of her life. She left the Centre to the CAA. After Keyes died in 1950, the estate passed to the Boston Children’s Aid Society.

Keyes’ nephew, Jonathan (Jay) Keyes, still resides in town.

James acknowledges that because the exhibit takes place during Pride Month, people may want to put a label on the women’s partnership. “History has not done that, and neither should we,” she says.

Pride Month is held to show support for the LBGTQ+ community, but it can also serve as an opportunity to accept and celebrate unconventionality in general, James says.

“There are all kinds of families,” she notes. “I hope people can open their minds to that.”

“A Boston Marriage” runs through June 30 at the CAA, 37 Lexington Road. Hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-4:30 p.m. and Sunday, 12-4 p.m. Admission is free.