By Luke McCrory — Correspondent

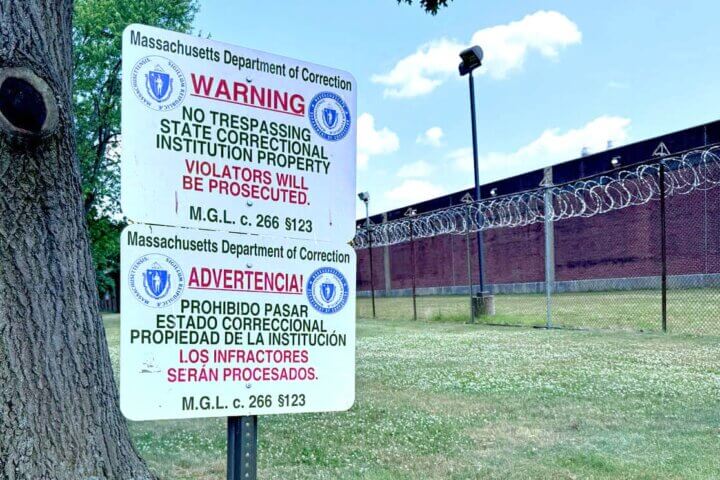

For more than 20 years, inmates and guards haven’t been the only ones behind the walls of MCI-Concord.

NEADS, a Princeton-based non-profit, has used the Concord prison to help prepare their dogs to serve people with disabilities. But the impending closure of the prison could be “devastating” for some of the outside dog raisers who work with the group, a raiser said.

“It broke apart the Concord raisers,” said volunteer Colleen Palmer.

‘Think of a place, we take them there’

Rick and Cynthia Ressijac and their black lab puppy, Hattie, visited their granddaughter in Laurel Jackson’s second-grade class at Thoreau this month — two miles from the prison where dogs like Hattie might have been working with inmates next year.

The students met Hattie one-on-one, marveling at her obedience to her owner and learning about her training.

“Think of a place, we take them there,” Rick explained.

“The movies, the mall, restaurants, hospitals, the commuter rail, the subway, a basketball game. They went everywhere. So all these dogs have to learn all these things because it’s so important that [when] they get matched, it’s ‘been there, done that.’”

Photo by Luke McCrory

The Ressijacs live in Ayer and have been raisers for NEADS since 2022. NEADS started operations in 1976 and has held slots available for eight to 12 dogs at MCI-Concord since 2002.

After dogs are trained for two years, NEADS pairs them with someone in need — a person with hearing loss or a physical disability; a child with autism or developmental disabilities; or a veteran with physical disabilities, hearing loss, or PTSD, among other conditions.

Once full-time raisers and their dogs complete the first year of training, the animals spend another year in NEADS’ Prison Pup program, learning and living alongside incarcerated men. Since 2002, NEADS has operated that program at MCI-Concord prison and the nearby minimum-security Northeast Correctional Center.

While raisers and prisoners do not interact, Rick said he saw the program in action when he worked at the federal prison in Devens.

“These inmates did incredible jobs with these dogs on training and handling… They’re getting training from NEADS all the time, but they take this to heart — it’s not just ‘I have a dog to hang out with,’” Rick said. “It’s incredible to watch these inmates work with these puppies and play with them.”

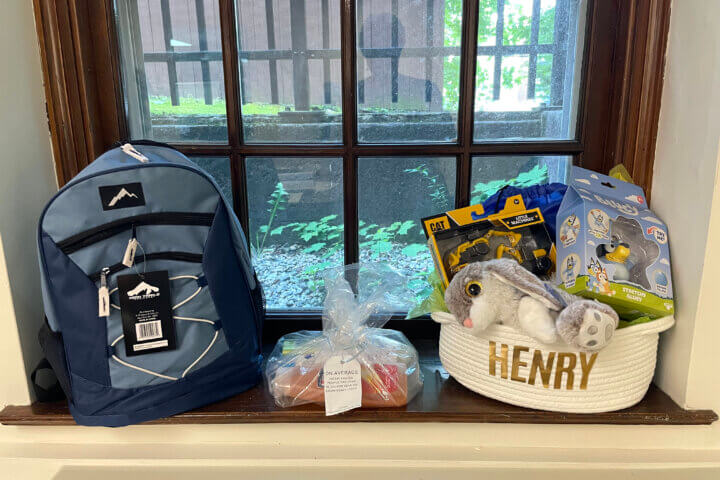

At Thoreau, Rick brought along “Rescue and Jessica: A Life-Changing Friend,” a children’s book “autographed” by every pup he trained in the past — Hazel, Bobby, Ricky, Mystic, Michael and Dolly. The couple last trained Dolly to work alongside MCI-Concord inmates. It is not yet clear where Hattie will now go next.

For the raisers, “While the training is hard, we can still have a dog,” Cynthia Ressijac said. “And we’re very happy to relinquish the dog when it’s time for them to go to their person because you know that you’re doing a really good thing.”

Her husband agrees. “You know you’re not abandoning the dog because they’re going off to a wonderful place. You know that it’s finite, and you know the purpose of it. Then you meet a few clients, and it really drives the purpose home,” Rick added.

“They tell you how much it changed their lives; they’re very grateful to us,” he said. “We don’t feel like we need that gratitude, but they truly appreciate it. It’s life-changing for them.”

Photo by Luke McCrory

‘Just not doable’

The Ressijacs, as full-time raisers, say they will not be affected by the MCI-Concord closure as much as weekend raisers.

“The closure is a definite impact because if you’re a weekend raiser in this area, let’s say if you live north of Concord, it’s 30 miles and one hour further south to get to Norfolk to continue with your pup,” he said. “It’s not theoretically the end of the line for raisers with this program. It’s just going to make it more difficult.”

Rick Ressijac said his family will stay involved with NEADS, and his daughter, Concordian Lauren Howard, is running in the Asics Falmouth Road Race this summer to raise funds for its work.

He said it would be more difficult for Concord-area residents to participate after the prison’s closure but that those who could would remain devoted to the program.

“It’s a big consideration,” he said. “It shows the dedication of these raisers that they’re going to continue to drive that additional distance and continue to work with the dog.”

But Palmer, currently raising her fifteenth dog for NEADS, calls the prison closure “devastating.”

Instead of taking care of her dog all week like Ressijac, Palmer picks up her pup, Cinder, at the prison on Fridays and trains him until Sunday, when she drops him back at the prison. As a Wakefield native, she relied on Concord’s relative proximity to continue her work as a NEADS raiser.

“Now that the Concord prison is gone, it’s a blow to NEADS as well because a lot of us can’t travel any further,” Palmer said.

“Concord was as close as we could get because to travel to Norfolk every single Friday and Sunday [is] just not doable. We couldn’t possibly commit that kind of time.”

With plans to live out of state for part of the year, Palmer says she intends to “still be involved as a mentor or perhaps a council member. But as far as having a puppy every weekend, unfortunately, it’s not meant to be.”

While her time as a NEADS raiser may be over with the shuttering of MCI-Concord, Palmer still hopes for the best for the program.

“It’s remarkable. It is a daily miracle what these dogs can do,” she said. “You never know what specialty they’re going to have. It’s magic.”

Dan Atkinson contributed reporting.