By Margaret Carroll-Bergman — Correspondent

One mark at a time, Kimberly Toney is building a history of Native Americans in the Northeastern Woodlands.

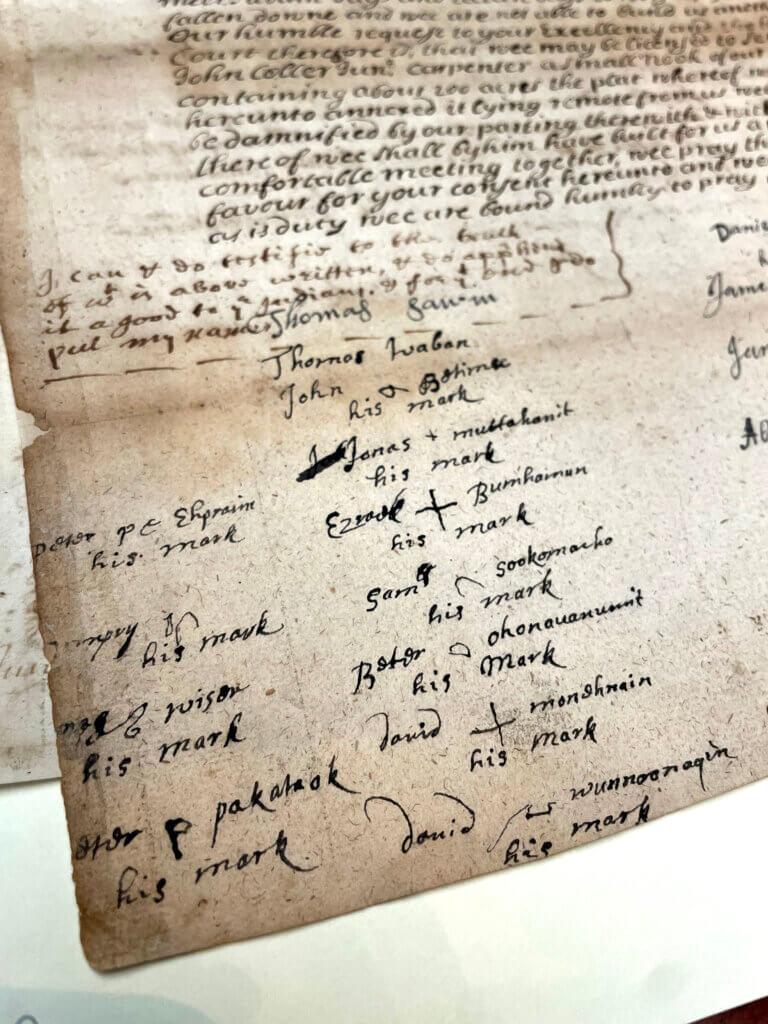

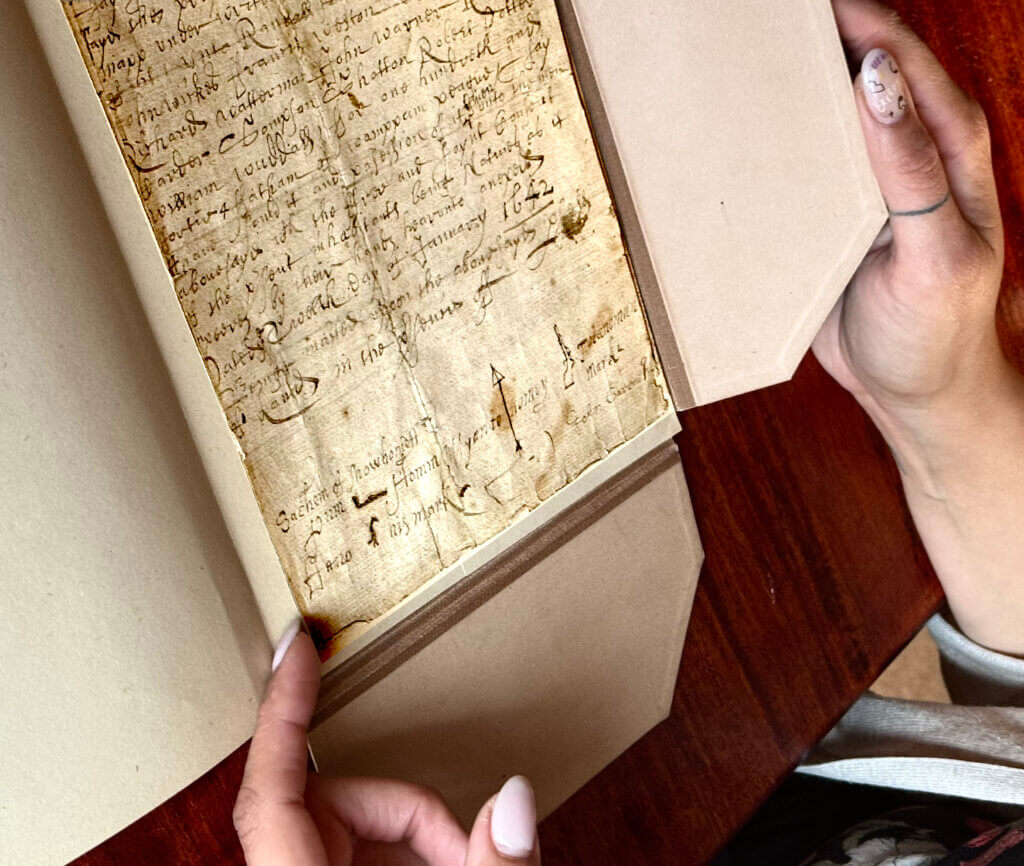

Toney is a member of the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmuc, and her study of 17th- and 18th-century land deeds — especially the marks or pictographs of the Native people who signed the documents — reveals the identities of some of these forgotten men and women.

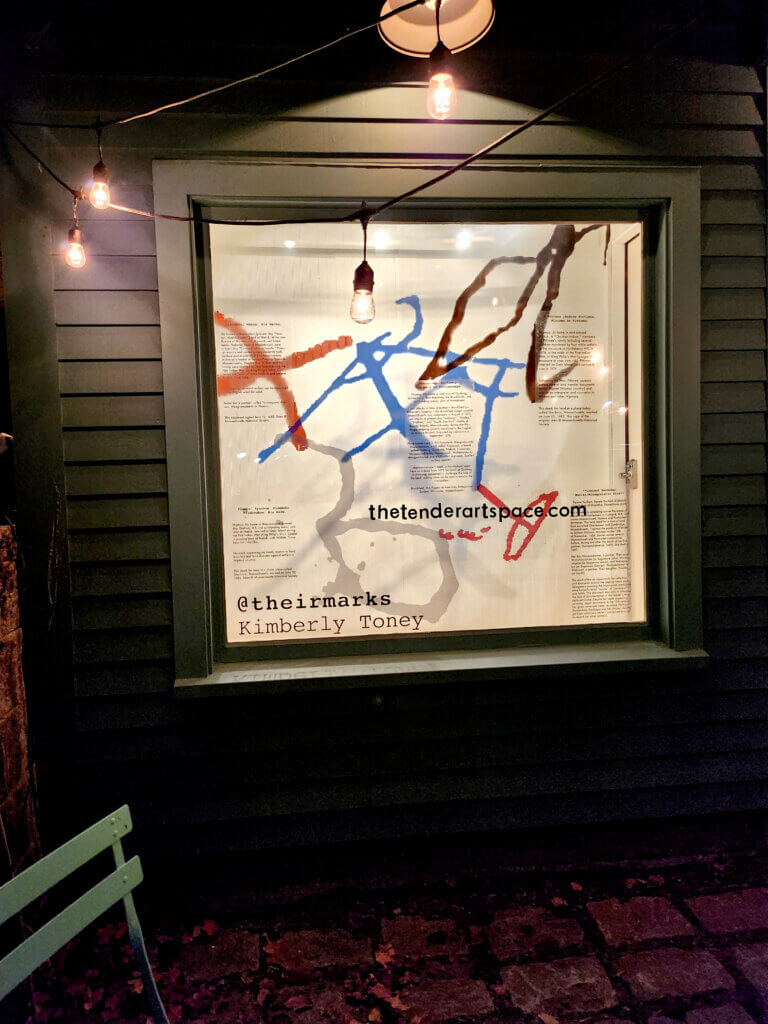

“Their Marks,” an installation at The Tender art space in West Concord, celebrates National Native American Heritage Month by highlighting some of those signatures and the people who left those marks.

The show developed out of Toney’s social justice public art project on Instagram at @theirmarks.

Toney, coordinating curator for Native American and Indigenous Collections at the John Hay Library and John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, says that during the 17th and 18th centuries, there were varying degrees of literacy in the Native communities.

Often, people would sign with a mark. Some pictographs are quite stylized; others might be a simple “X.” Neither the early settlers or the Native Americans were fluent in each other’s language or culture.

Toney’s research dispels many myths associated with how the Europeans acquired land from the Indigenous people.

“People easily assume that Native people ceased to exist on the landscape at a particular point in time. They want to believe there were not many Native people living here and land was free for the taking,” Toney says.

“But there is actually a very robust paper trail of dispossession, of forced assimilation, that’s happening between Natives and settlers coming here, and people appear by names in the documents who talk about who they are related to,” she says.

“It’s really exciting in terms of reconnecting and reinvigorating the lives of these people.”

Signature art

“The art is coming from the pictographs that were created by Nipmuc or Wampanoag or Narragansett or other folks in the 17th or 18th centuries,” said Toney.

“I do a little bit of writing about who that person was, where their homelands were, what the documents can tell us about the circumstance of the land deed — anything I can ascertain about the kinship or relationships of that person or people,” Toney says.

Katherine Spencer, curator of The Tender, invited Toney to show her work after following “Their Marks” on Toney’s social media feed.

“Each month we offer the space to an artist. It’s where people can bring their voice to the public,” Spencer says of the “micro” gallery. “Each November, I try to show an Indigenous artist. Kim’s work humanizes Native Americans. I love that her work revealed these drawings — art from Indigenous people.”

One pictograph depicts a thunderbird and belongs to Mattawammppe, who led attacks against colonizers in 1675. His mark was found on a deed from 1673 for lands at Quabog, the area of present-day New Braintree and surrounds.

Another mark, a scripted letter “A” found on a 1682 deed for Sherburne, Massachusetts, belongs to Andrew Pittimee, a “Christian Indian.” Members of Pittimee’s family, including several children, were killed by four Englishmen during the massacre of Hurtleberry Hill in 1676.

Reclaiming a language

Toney is also concerned with reclaiming the language of the Indigenous peoples, especially in the places renamed by European settlers.

It’s her hope that people might see a word on a sign that looks like a Native word and be able to read and understand its meaning.

“There are real and deep histories of Native presence on the landscape, and there is a way we can move past romanticizing the idea of Indigenous histories or connections between Indigenous people and settlers,” Toney says. “We still exist, and … there is so much more we can know.”

“Their Marks” is on view at The Tender, 45½ Commonwealth Avenue, through November 30 and online at thetenderartspace.com.