On June 17, 1976, on the fourth anniversary of the Watergate break-in, seven students at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School re-enacted the operation by bungling a break-in at the principal’s office.

I was one of them.

I remember it as if it was almost 50 years ago (i.e., I’m having difficulty remembering it), but I recently contacted Dan Harper, one of my fellow teenage plumbers, and he reminded me about aspects of the operation. Apparently we brought a small box of dead insects (i.e., “bugs”) and dumped them on the principal’s desk. We did this ostentatiously in order to get caught, on the understanding that if we failed to be foiled in our mission, we would have blundered the successful re-enactment of a bungled operation.

That’s the kind of historically accurate nerds we were.

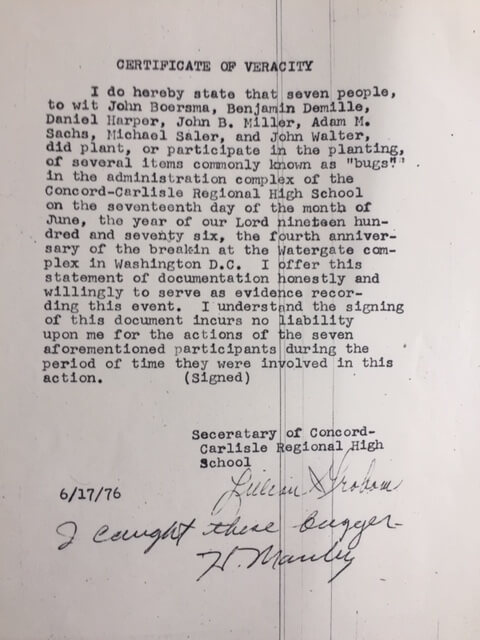

It was the principal’s secretary who was roped into nabbing us, and we had her sign an affidavit to attest to our botched crime. Dan recently sent me a copy of the document. It shows that the vice-principal Mr. Manley signed as well, adding, “I caught the buggers” (nice pun).

Looking back on it, U.S. history nerds had some good material to work with in those days, the recent historical events being mostly benign, with the Vietnam War over and the assassination of President Kennedy 13 years (a seeming lifetime, so to speak) in the past.

The Watergate break-in was so comical it spawned at least two comedies (the delightful film Dick and the current HBO series White House Plumbers), as well as the superb “paranoid thriller” All the President’s Men, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

Those Washington Post reporters were true heroes in our minds, and the ending — the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974 — was highly satisfying to us. The Redford/Hoffman film had come out just three months before our re-enactment, and it was still fresh in our minds (we’d all seen it).

U.S. history was then not a contentious subject to be taught in high school. I remember immigration presented as a positive influence on the nation, and the Civil War, slavery and Reconstruction taught without recrimination or controversy. The one time I took my history teacher to task was when I thought he was being too easy on the so-called “robber barons” of the late 19th century (the Vanderbilts, Fricks, Astors and Carnegies), and he conceded the point. This didn’t stop me from becoming interested in this wealthy crowd; I wrote a paper about one of the Vanderbilts and made a point of getting my parents to take me to the millionaires’ “cottages” in Newport, Rhode Island.

There was a lot of interesting local history, Concord being the birthplace of the American Revolution (we all enjoyed the Patriot’s Day parade on April 19th — celebrated on that day and not the nearest Monday, as happens now), and the town’s famous 19th-century writers and thinkers, such as Emerson, Alcott and Thoreau.

But you didn’t have to live in Concord to enjoy U.S. history without controversy. President Gerald Ford was seen as a good-natured bumbler no one had actually voted for, and he was regularly satirized by Chevy Chase on Saturday Night Live. Jimmy Carter and his colorful Georgia family were entertaining enough to be gently joshed by Garry Trudeau in his comic strip Doonesbury, which was de rigueur reading.

After Nixon and the Vietnam War we were lucky to enjoy such a peaceful period that the biggest environmental concern seemed to be litter (according to the TV ad with the crying Indian — as he was then identified, though he turned out to be an Italian-American actor) and the greatest economic concern seemed to be inflation. President Ford memorably wore a badge that read “WIN,” which stood for “Whip Inflation Now,” though wags pointed out that if you wore it upside-down it said “NIW,” which stood for “No Immediate Miracles.”

A Carter campaign leaflet from 1976 features the opening quote, “Our whole system depends on trust. The only way I know to be trusted is to be trustworthy. To be open, direct and honest. It’s as simple as that.” He managed to offer this without vilifying anyone by name or claiming victimhood on his behalf or anyone else’s. He didn’t allege that the other party “hated America.”

I worry what kind of historical re-enactments the current crop of high school history nerds could engage in, without resorting to staging a would-be Trump rally on the school’s football field or orchestrating a lockdown to echo a school shooting. Could they announce an airborne toxic event to commemorate the anniversary of Covid, or ignite a riot to re-enact the January 6th Capitol attack? None of these sounds particularly fun.

The Watergate scandal strikes us almost impossibly quaint now, though it was significant enough at the time. All the “-gates” that followed have signaled the corruption of politics, but in 1976 it inspired an amusing would-be break-in at a high school principal’s office. We could only wish for such a benign theatrical event today.

J.B. Miller is an American writer living in England, and is the author of My Life in Action Painting and The Satanic Nurses and Other Literary Parodies.