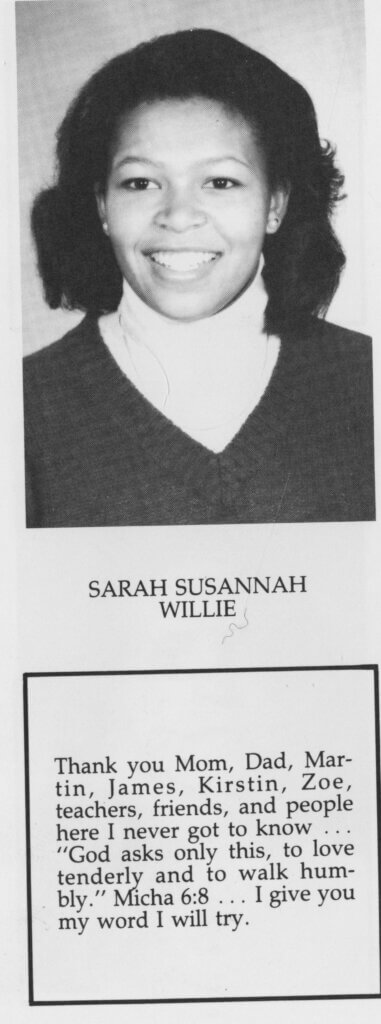

When one young Concord woman began her journey to a career, pursuing social justice was a priority. Her path led her to the president’s seat at Smith as the second Black woman to occupy that chair at Northampton’s elite women’s college.

When Sarah Willie-LeBreton moved to town as a grade-school child, along with her Black father, white mother, and two brothers, the family knew the public schools were excellent.

“Concord was a wonderful place to grow up, but more homogeneous than I might have wished,” the 1982 Concord-Carlisle High School graduate said.

She remains close to her fifth-grade teacher from Thoreau, Judith Sallett, who left teaching to become an attorney. “I discovered she was a Smithie and she was able to come to the inauguration” at Smith in October 2023, Willie-LeBreton said.

Not being the only students of color was important for the family too. Concord ticked off that box. The town was part of METCO, a Boston-based program that brings inner-city children to schools in participating suburbs.

Willie-LeBreton’s father, who graduated from Morehouse College with Martin Luther King Jr., inspired and guided her through her school years and her career, she said.

Charles Willie was a court-appointed school desegregation master who worked to desegregate Boston public schools in the 1970s. The Harvard University professor preached the sermon during a 1974 Episcopal Church service when 11 women were ordained, years before the church formally allowed the practice.

When a dad like that wants his daughter to be on the front lines of social justice, that’s what happens, Willie-LeBreton said.

As a child, she experienced his warriorship for civil rights first-hand.

In 1972, a local CCHS graduate came back to school and assaulted a METCO student. A melee ensued, involving 300 or more students and staff. As a result, the METCO students’ parents voted to leave the high school.

Willie went to local school committee meetings to learn more about the problem and then lobbied for CC to apologize. He succeeded, and the Boston students returned, his daughter said.

His involvement in civil rights came at an expense. He received death threats through the mail both at home and work, Willie-Breton said. The family stopped traveling to Philadelphia due to bomb threats.

“It was an intense time,” she said.

“Watching that kind of courage in action said we could do things differently.”

So, she has.

Willie-LeBreton was active in leadership in her high school years. She was president of the student government.

“I felt very supported and challenged and encouraged by my public-school teachers in Concord,” she said.

The sociologist has suggestions to encourage students.

She urged parents and educators to nurture the curiosity of young people. “That curiosity will ultimately save us,” she said.

Making advances requires being strategic together, but using handheld devices to seek answers means students are less likely to interact with parents and peers.

Putting those phones away will encourage interactions with strangers, whether nodding to people while walking the bike path and smiling, chatting, and assisting others while out in public.

Willie-LeBreton also had a reminder for our communities: “The gains of any liberation movement are fragile, and our democracy is fragile.”