By Laurie O’Neill — Laurie@concordbridge.org

It has all the makings of a hit movie: danger, defiance, secrecy, suspense, and the triumph of an underdog.

But it’s the real-life story of the Wright Tavern, Concord’s oldest commercial structure and arguably one of its most historically significant buildings.

Built in 1747, the iconic reddish-brown Tavern did not only bear witness to the events of April 1775 from its central location between the meetinghouse, now First Parish, and what was once the training grounds for the militia and is now a road.

It also served the Patriot cause.

‘Fifteen minutes of fame’

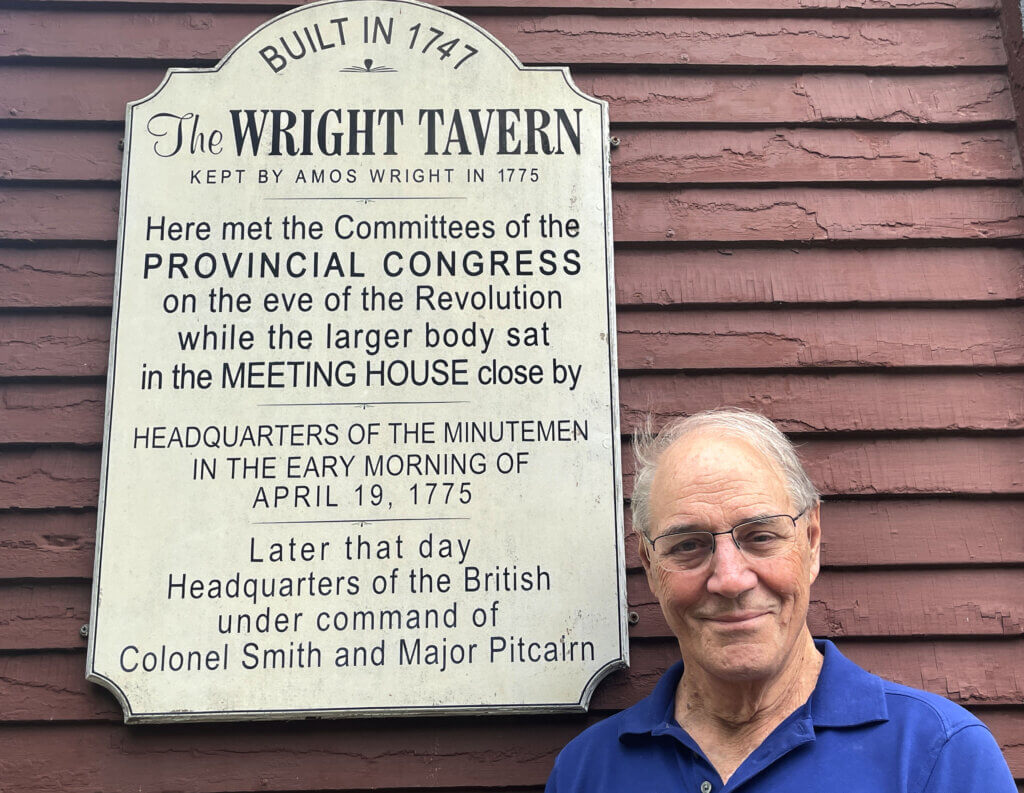

Tom Wilson, who leads the Wright Tavern Legacy Trust, collected numerous stories about the building in a book titled “Concord’s Wright Tavern: At the Crossroads of the American Revolution,” which comes out this month.

All book proceeds will go to the Trust, which is working to reopen the building that has been closed to the general public for nearly four decades, open only for guided tours, meetings, and events.

In the book, he traces the building’s history, noting that it wasn’t always a tavern and inn. It was at times a stable, a manufactory of cheap goods such as hair balm, a tinsmith, a bakery, and a seller of illegal liquor, among other businesses.

And he corrects a common misconception. Amos Wright was never the proprietor. He worked at the Tavern only briefly but at the most dramatic time in its history: the beginning of the American Revolution. “It was his fifteen minutes of fame,” local historian Robert A. Gross says of Wright in a foreword to Wilson’s book.

Townspeople began to call the place Wright’s Tavern, and the name stuck, especially after an 1835 book on Concord history by Lamuel Shattuck referred to it that way.

Secret meetings

The Tavern played a significant and dramatic role in the months preceding the battle with the British.

In October 1774, some 286 delegates of the First Massachusetts Provincial Congress, led by John Hancock, met in secret in the meetinghouse and the Tavern. They devised a plan for Massachusetts to separate from British rule and set in motion the eventual battle for independence.

On April 19, 1775, some 150 Minute Men and local militia members assembled at the Tavern at 5 a.m. after being warned that the British were approaching. Dr. Samuel Prescott had ridden in from Lexington — Paul Revere was captured along the way and William Dawes turned back — and Concord’s courthouse bell was pealing an alarm.

At 8 a.m., once the Patriots had left, the British Redcoats, commanded by Colonel Francis Smith and Major John Pitcairn, occupied the building. The two forces clashed at the North Bridge — and the rest is history.

While the men were preparing for battle, the women did their part, hiding precious items such as silverware — and defying the British. Reportedly, Lydia Taylor was serving in the Tavern when the Redcoats burst in. With horror, she realized that four musket balls were lying in plain sight, and she slipped them into her pocket.

When the bill came due, Mrs. Taylor accidentally handed over the musket balls instead of coins. “Madam, what do you intend to do with those?” asked a British officer. Though frightened, she boldly declared, “Sir, I would use them in a firelock if I had one.”

A year-round gathering place

In 1885 two local men, Reuben Rice and Rockwood Hoar, grew concerned about the future of the building, fearing that it could become “a disreputable drinking establishment,” says Wilson. They purchased the Tavern and turned it over to the Society of the adjacent First Parish, which owns it to this day.

It became a restaurant and an inn, and First Parish has worked to preserve and maintain the structure, which in 1961 was designated a National Historic Landmark. Largely untouched since the Tavern was built are the first floor’s taproom and meeting areas, with their low ceilings and slanting, wide-board floors. There, Hancock, Samuel Adams, and other notable figures of the day changed the course of history.

The Tavern was leased to the Concord Museum for a few years, and the building has housed professional offices. After a task force debated possible uses for the Tavern, the Legacy Trust was formed in 2021. The non-profit 501(c)(3) organization is rehabilitating the structure with the intention of opening it to the public as a year-round gathering place, a center for exploring democracy, and an immersive learning museum.

The Trust envisions the Tavern as continuing to offer meeting space and guided tours, performances and exhibits, and, if it can obtain the appropriate approvals, light fare and typical Colonial ale and rum drinks.

Funding from sources including the Concord Preservation Act has paid for about $400,000 in structural repairs to the building, especially its foundation. “It’s really solid now,” Wilson says. But more money must be raised to continue the work.

Much still must be done for it to reopen within a hoped-for couple of years, Wilson says, adding, “We have miles to go before we sleep.” But the Trust is determined, he says, to have the Wright Tavern “take its rightful place in the stories of Concord’s history and the founding of our country.”