By Erin Tiernan — Erin@concordbridge.org

An aging wastewater treatment facility on the MCI-Concord prison property is essential to development there and at other sites — but officials worry it could saddle the town with ballooning infrastructure costs.

Deputy Town Manager Megan Zammuto said Concord is in the “early days” of reviewing a proposal to buy the facility from the state.

“The town has a serious wastewater capacity issue, which is the driver behind the whole discussion,” Zammuto told The Bridge.

Gov. Maura Healey’s administration plans to sell the prison to a residential developer amid an ongoing housing shortage driving up the cost of living in the Bay State. Town officials said the property’s wastewater treatment plant is crucial to making that a reality because Concord’s facility is already at its limit.

Mark Howell, the Select Board’s clerk and liaison to the town advisory board overseeing redevelopment planning, said that building options depend on a “fixed amount of capacity” available for wastewater treatment, drinking water, and electricity.

“Once we begin to understand how much of that capacity we have, we can know how much development can go inside,” Howell said.

Making it Concord’s problem?

MCI-Concord Advisory Board members, however, were skeptical of a deal that could put the town on the hook for infrastructure costs and liability.

“When we talk about whether we’re on the same team here, I think we’ve just got to be honest that they want more housing and whether it’s our problem to pay for the infrastructure,” board member Elizabeth Akehurst-Moore said. “I’m not sure that’s on their mind, so we have got to look out for our own interest as much as possible here.”

The 40-year-old facility needs about $25 million of investment in the next five to 10 years “to restore it and make it a viable treatment facility for the next 20, 30 years for this current capacity,” Concord Public Works Director Alan Cathcart said at an early September meeting. Expansion would cost taxpayers even more.

Town officials have contracted with environmental engineering and design firm Weston & Sampson to conduct a technical review of the existing infrastructure and future needs. Zammuto said the findings in this report would drive the negotiation process with the state over whether to purchase the wastewater treatment facility and what the terms would look like if the town moves forward.

Ultimately, such a purchase would require Town Meeting approval.

What’s in the deal

The deal, set in motion by the same legislation that shuttered the 146-year-old prison in July, gives Concord the right of first refusal over the state-run wastewater treatment facility. The legislation lays out a timeline for the negotiations.

The state Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance formerly offered the facility to the town on August 26. The offer letter expires on February 24. Before the town makes its decision, Zammuto said, an exhaustive audit of the facility’s condition and Concord’s needs will take place.

“We plan to schedule a meeting with DCAMM later this month to begin to discuss the offer, the technical details and condition of the plant, and the timeline for further discussion,” she said.

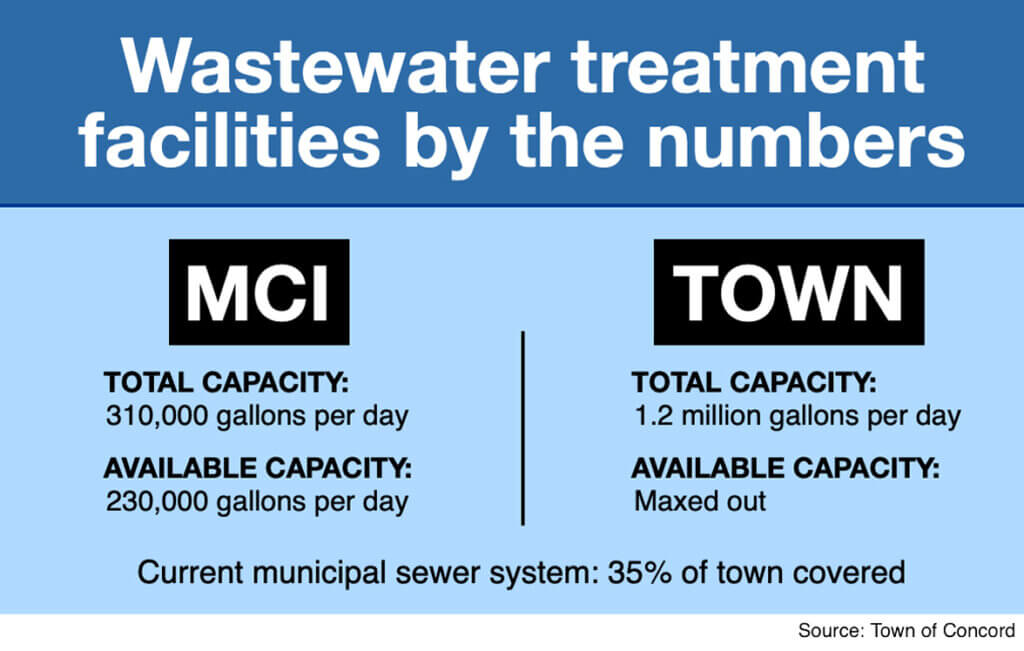

The 40-year-old facility is permitted to treat 310,000 gallons of wastewater per day. It primarily served the prison, but about 80,000 gallons of its daily capacity is still being used by the state police barracks, a Massachusetts Department of Transportation facility, and the minimum-security Northeastern Correctional Center facility, where about 200 inmates reside.

Crunching the numbers

The remaining 230,000 gallons of daily capacity are crucial to furthering discussion about the size and scope of development to come on the 51-acre prison property, Cathcart said.

“The town is at its allowance allocation at our wastewater treatment plant, so we need additional capacity,” Cathcart said. A planned 201-unit apartment development on Baker Avenue will put the town at its limit in terms of managing wastewater, he said. Developers were able to push through permitting for NOVO Riverside Commons under the state’s 40B affordable housing law, as it includes 51 designated affordable apartments.

Without more wastewater management ability, the town risks a development moratorium at a time when new state policies would aggressively expand access to affordable housing, Cathcart said. It would complicate Concord’s ability to meet new MBTA zoning regulations and put the town at risk of losing some state funding.

“We’re not just sitting waiting for a problem; we’re proactively trying to manage the fact that we believe we’re at effective capacity,” Cathcart said. “We don’t want a moratorium.”