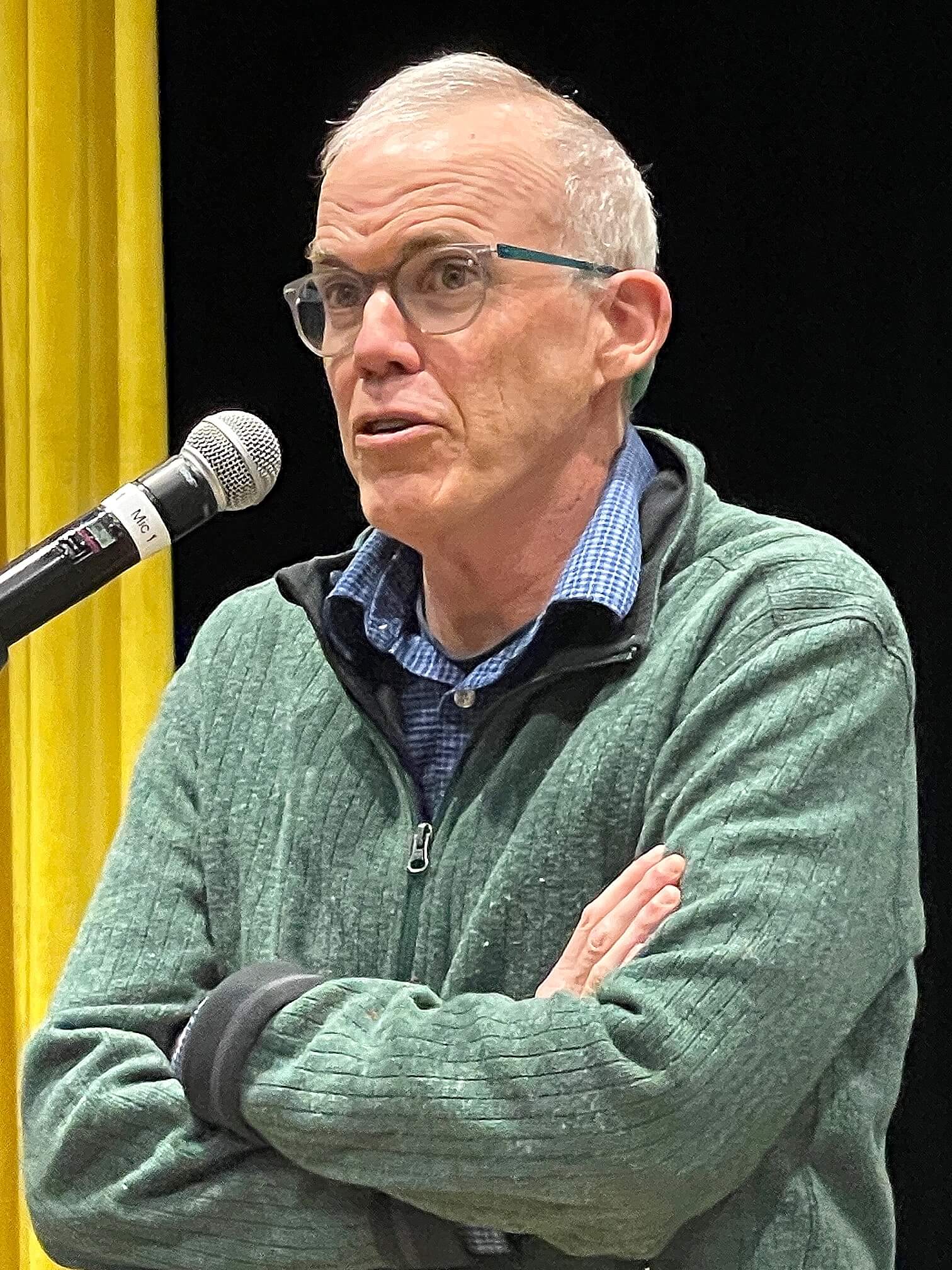

Bill McKibben urges his audience to “get out of your comfort zone”

To a packed auditorium at Concord-Carlisle High School on April 2 and to hundreds more on Zoom, author, environmentalist, and activist Bill McKibben rolled out a rousing argument meant to get people, both young and older, engaged in the fight against climate change.

First Parish in Concord’s social action community and Concord Public Schools, among a number of organizations, hosted McKibben for a talk billed as Climate Change, Migration, and Racism. The event was a memorial lecture for Peter Nichol, a beloved local educator and environmentalist who passed away last year.

McKibben recalled growing up in Lexington, where in 1971 he observed two events that to him reflected the change from group responsibility to self-interest. The first was an anti-war protest by Vietnam Vets, led by John Kerry in a march from Concord to Lexington. After the group was refused permission to bivouac on the green, the vets were joined by several hundred townspeople. All were arrested, including McKibben’s “mild-mannered” father. “It was a sign to my ten-year-old brain that we were still engaged in the project of trying to build a great country together.”

The second was a proposal for an affordable housing complex by the Suburban Responsibility Commission, which wanted a less economically segregated town. “Everyone signed off on it, but townspeople demanded a referendum, and in the privacy of the voting booth, they defeated the margin two to one,” said McKibben. “This is what racism looks like in suburbia.”

These events were “hallmarks of two possible ways to look at the world: America as a group project and privatized ideas of property values.” He noted that his family home, purchased for $30,000, recently sold for $1 million, was immediately razed, and was replaced by “a house that looks like a cross between a junior high school and a medium security prison.”

McKibben, who has received several awards including the Gandhi Peace Prize, lives in Vermont and is the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College. He has been at the forefront of climate activism for decades and has written twenty books beginning with “The End of Nature” in 1989, considered to be the first book about climate change for a general audience. His latest is “The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened.”

McKibben helped found the organization 350.org, the first global grassroots climate campaign, and played a leading role in launching opposition to big oil pipeline projects including Keystone XL and the fossil fuel divestment campaign, which is said to be the biggest anti-corporate campaign in history, with endowments worth more than $40 trillion from divesting in oil, gas, and coal.

His message has evolved by necessity since his first call to arms about climate change. “It is too late to stop global warming,” McKibben said early in his remarks. “It wasn’t too late in 1989. If we’d worked with resolve then, we’d be in a different place. I guess I didn’t write a good enough book,” he added with a smile. “But we can deal with the hand we’ve been dealt. “We have cards to play.”

Those cards include the fact that solar and wind power prices have dropped dramatically. “The cheapest way to get the energy we need,” he said, “is to point a piece of glass at the sun.” Emissions, he reminded the audience, “need to be cut in half by 2030 to meet the targets we set in Paris.”

Another card is that young people, led by such activists as Greta Thunberg, are dedicating themselves to the issue. They helped launch the Sunrise Movement, which brought us the Green New Deal, he said. Still another is that the older generation, who worked so hard decades ago on issues including reproductive rights, voting rights, and Civil Rights, which are being steadily dismantled, is reengaging.

McKibben has been dedicating his time to a new organization, Third Act, aimed at engaging activists over the age of 60. Unless we make changes, “we’re poised to leave behind us a world with melting poles and a country where people invade the Capitol and kill police officers in order to stop the counting of votes,” he said.

Last month, a Third Act event called Day of Action brought hundreds of demonstrators to four banks across the country that are the biggest lenders, at the collective tune of $1 trillion between 2016 and 2021, to the fossil fuel industry: Chase, Bank of America, Citibank and Wells Fargo. It was the largest climate action ever undertaken by older people, he said. “We leaned into the ‘We’re old’ thing,” McKibben said. “We closed them down by sitting in rocking chairs.” At one event demonstrators carried a banner reading Fossils Against Fossil Fuel.

Giving more attention to the issue is critical. News of the indictment of Donald Trump, he said, shouldn’t have overshadowed a report earlier that day in a preeminent scientific journal about how melting ice is slowing deep-ocean currents, which take nutrients out of the depths and cycles them, moving heat in and out of the ocean. This could be catastrophic to the seas being able to support life.

Melting sea ice and shifting rainfall and temperature patterns around the globe are wreaking havoc, McKibben said, and prompting mass migrations. Parts of Pakistan, for example, got 800 percent of their annual rainfall in three weeks last fall and the disaster displaced 33 million people. “There’s not a place in the world that can cope with that.” The UN estimates “that we could see 1 to 3 billion climate refugees” after weather catastrophes, he said, “which can discombobulate the politics of the area.” Pakistan, he noted, has 180 million people but contributes “well less than one percent” of all of the carbon in the atmosphere.

“One too many people tell me that it’s up to the next generation to solve this,” McKibben said, “but that’s both ignoble and highly impractical.” Young people, “for all of their energy, idealism, and intelligence, don’t have the structural power to get everything done by themselves in the time that it needs to be done. They need backup. Who has that structural power? People with hairlines like mine,” he said, adding that “70 million of us are over the age of 60, and there might be a couple of them in this room,” which drew appreciative laughter.

Of Concord, he said, “It’s a comfortable place, as good as it gets on Planet Earth. But you need to get out of your comfort zone.”

Young people “don’t need to be the cannon fodder here; an arrest record may not be the best thing for their resume. But one of the blessings of being older,” he said, “is that after a certain point, what the hell are they going to do to you?” Of having been to jail a few times, McKibben said, “It isn’t the end of the world; the end of the world is the end of the world.”

McKibben said he wasn’t advocating getting arrested, and that there are many other ways to make a difference. “Do it in the right spirit,” he urged. “You can be a huge part of the work that needs doing.” He cited a Third Act project called Senior to Senior, whereby older people wrote letters to high school seniors, urging them to register to vote. “Only 10 percent of high school seniors vote in their first election,” McKibben noted. “And letter writing is a kind of superpower possessed by those of us of a certain age.”

Answering an audience question about what policies Massachusetts should adopt, McKibben said that any new fossil fuel infrastructure should be stopped and old infrastructure should be retrofitted. He referred to the hangar expansion proposal for private luxury jets at Hanscom Field this way: “It’s the single most ludicrous idea I’ve ever heard. They ought to rename it Carbon Dioxide Field. Find a way,” he added, “to knock that down fast.”