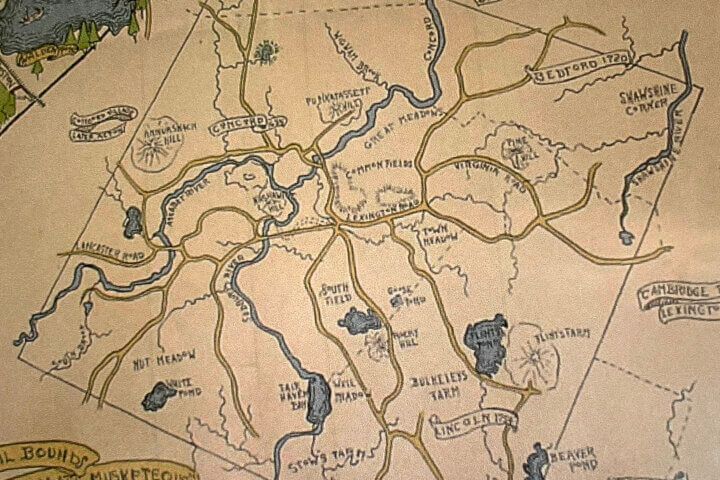

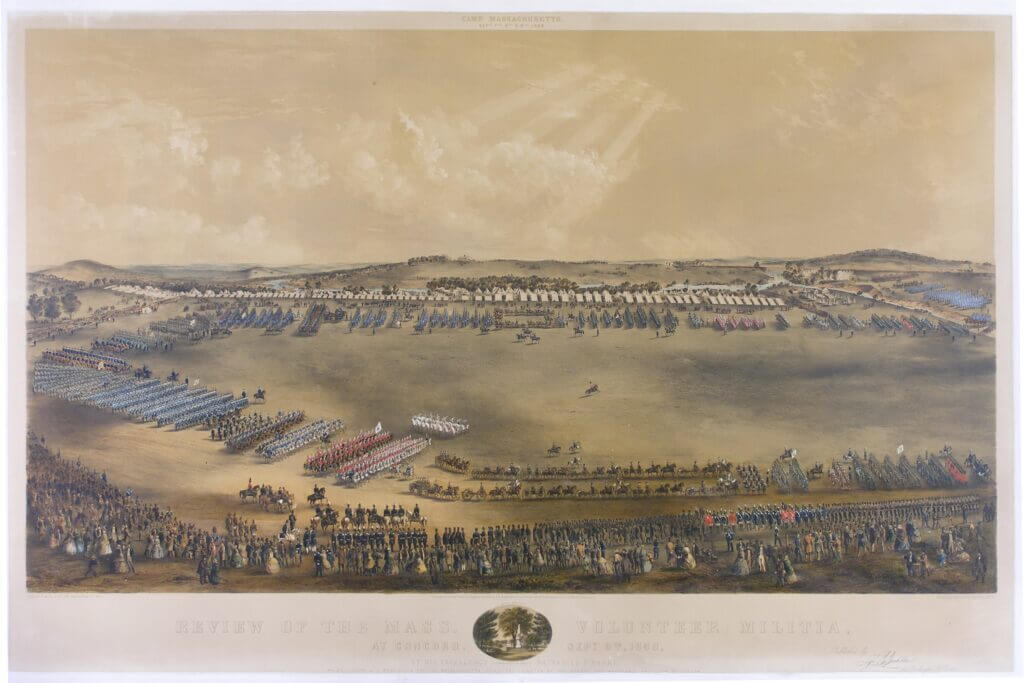

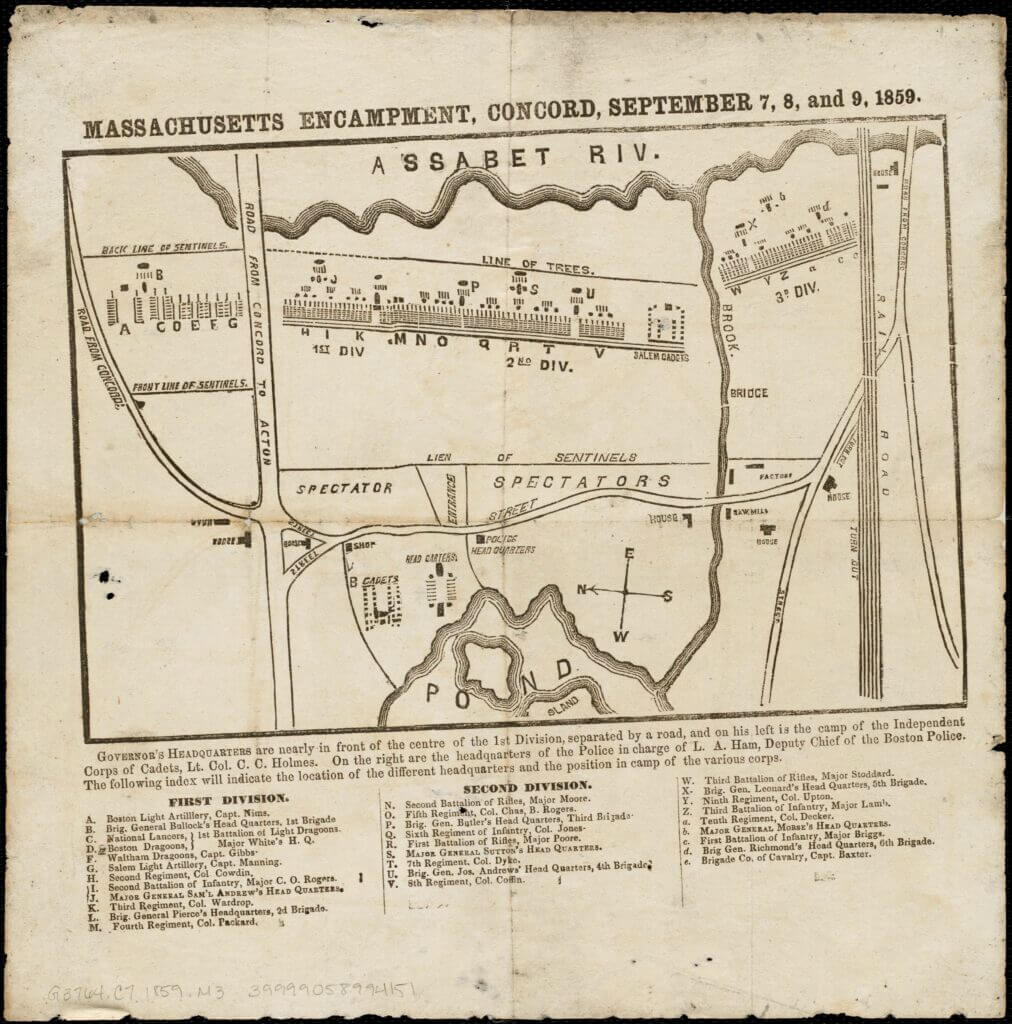

More than 5,000 men, with their guns and drums, horses and carts, and tents and food, set up camp at the confluence of the Assabet River and Nashoba Brook, along present-day Commonwealth Avenue, during the last days of summer in 1859.

Camp Massachusetts, comprised of all the “Volunteer Militia of the State,” claimed to be the first gathering in the country of all the troops from one state. Like any good, days-long fair, the military pageantry drew crowds of visitors.

Despite the music and festive crowds, the encampment was serious business. The Mexican-American War had ended 11 years earlier. The American Indian Wars were ongoing.

The country’s military would soon face a new challenge. Civil War was coming. Abolitionists called for an end to slavery. Southern slave-holding states disagreed. The country was coming apart.

Patriots joined militias in their own towns, training throughout the year, similar to our National Guard. Each Massachusetts militiaman agreed to a five-year enlistment. The U.S. Army would rely on these men to fill the ranks if the country went to war with itself.

Camp Massachusetts offered a chance for the men not only to drill, but to celebrate and honor the contributions made in Concord during the American Revolution, which started more than 80 years earlier.

Massachusetts officials were determined that the 19-century militia men would be good visitors. Intoxicating beverages were strictly prohibited, as were visitors during specific hours. Even then, except for the last day, visitors needed a pass.

Sentinels manned the borders. Local police were all part of the successful plan to keep things peaceable in Concord.

Logistics were key for organizing camp. Breakfast was peas on a trencher. For dinner, roast beef. Supper victuals were not specified.

Any man who did not remain in camp when required would not be paid. The men followed a strict schedule for waking, sleeping and even to dismantle their tents at the end of the gathering.

The Fitchburg Railroad made getting to Concord and back home for harvest possible. The tracks were alongside the southern part of the campgrounds.

Companies from Fitchburg, Leominster and Ashburnham set up closest to the tracks. Others had a longer walk to their assigned tenting grounds.

Over the course of three days, there was plenty of time for Concordians and up to 100,000 others to see the militias at work.

One day, all the troops marched into Concord center and back to camp, a seven-mile journey. They stopped by turns at the battlefield monument, cheering and listening to the bands play patriotic songs like “Yankee Doodle” and “Hail Columbia.”

The Revolutionary War monument was just two decades old. The bridge itself was long gone although the roadway remained.

The encampment caught the notice of the southern states, the soon to be enemies of the north, rather than peaceful fellow citizens.

The Charleston Mercury, in South Carolina, reprinted a report from the New York Journal of Commerce on its front page.

The northern reporter praised the Concord gathering of warriors:

“The most of the same 6000 troops were composed of infantry, and beautiful was the spectacle of their bayonets shining beneath the rays of the sun. But most striking were the clouds of dust rising one after the other. We could easily conceive them to be the smoke of battle as they deal death to the enemy.”

Less than two years later, the first shots of the civil war sounded just outside Charleston, at Fort Sumter, which began construction during the War of 1812 to protect the port.

The Adjutant-General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts prepared a glowing report of the encampment in the annual report for 1859. Most of the information in this article was taken from the report.