Concord is looking deeper at making a nearly century-old part of its history a thing of the past.

The Select Board voted 3-1 this month to cloak three cast-iron markers that commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony after members of the town’s Historical and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Commissions called the signs offensive to Indigenous people.

They also argued that the markers aren’t just derogatory — they also promote fantasy over fact.

“These signs are offensive to the over 15,000 indigenous residents of our state and are perpetuating lies to the nearly one million visitors the town experiences each year,” DEI Commission Co-Chair and local tour guide Joe Palumbo — who pressed the board to vote on the signs — wrote in a short essay entitled, “Concord, We Have Work to Do.”

Palumbo said like many New England towns, Concord long put forward a “false mythology of a warm and peaceful transition from the original Indigenous people to the new English arrivals in the early 1600s.”

Taking down the signs, he says, would be a first step in the “long process of reconciliation and atonement for the unceded lands now known as Concord.”

A briefing Palumbo prepared for the Select Board highlighted issues with the trio of signs:

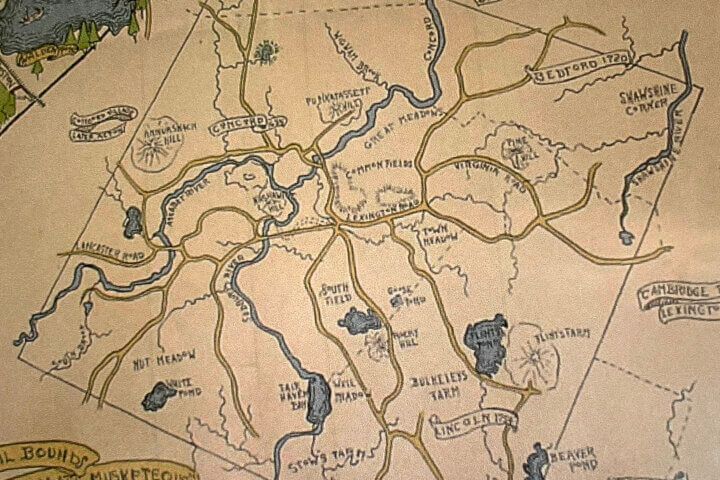

- The Jethro’s Tree sign marks the location of an oak “beneath which Major Simon Willard and his associates bought from the Indians the ‘6 myles of land square,’” but Palumbo says there’s “no evidence that the local indigenous peoples ever [willingly] sold the land” — and also that the location of the tree is “unverified and disputed.”

- The Milldam sign claims to mark “the site of an Indian fishing weir,” but Palumbo says “local [archeological] experts believe it was unlikely to have existed here.”

- And like the Milldam marker, he writes, the First Settlement sign “ignores the thousands of years of previous indigenous settlement” before the colonists arrived.

Two of the three signs, which were presented to Concord in 1930 as part of a commonwealth-wide program, refer to “Indians.” The term is still in use, including by branches of the federal government, but some consider it anachronistic and inaccurate. Per the Smithsonian, just for one resource, “Native American has been widely used but is falling out of favor with some groups, and the terms American Indian or Indigenous American are preferred by many Native people.”

We “are aware of the tribal groups who lived in Musketaquid” — the area later incorporated as Concord — including the Nipmuc and Massachusett, Palumbo said. “Any historically accurate signage should refer to them by name.”

The signs, located in Monument Square and near Orchard House, also bear the Massachusetts seal, which is currently under review by a state commission with attention to “those features that may be unwittingly harmful to or misunderstood by the citizens.” As town Historical Commission member Nancy Fresella-Lee told the Select Board, the seal depicts “a severed arm wielding a sword over the head of the Native American man standing at peace.”

“Even if you don’t know anything about the signs,” said Fresella-Lee, who’s drafting on an extensive report on the markers, a “child [can] look at that and say, ‘Why is someone wielding a [sword] over [a] stereotyped Native American?”

Palumbo also said the Visitors Center received an October complaint from a person who was visiting or working in Concord and found the signs offensive. That complaint moved up the chain to the Town Manager’s office and then over to DEI, he said, which is how it ended up before the Select Board.

On a motion from Board member Mark Howell, he, Terri Ackerman, and Clerk Mary Hartman voted in favor of covering the signs. Chair Henry Dane voted against, saying he wanted further study before making a precipitous move. Member Linda Escobedo was not present for the November 6 vote.

Howell, the Board’s liaison to the DEI Commission, said what ultimately happens to the signs “is a bigger question,” but since there’s reason to believe they’re causing offense, it was better to cover them “rather than let the harm continue to exist while we try to decide what to do.”

The board asked the DEI and Historical Commissions to work on a proposal for the markers. That could include removal, replacement, or incorporation into an educational exhibit.

Now, the issue goes to the Historic Districts Commission, which Deputy Town Manager Megan Zammuto said has purview over “sign modification.” At press time, HDC was scheduled to broach the question at its November 16 virtual public meeting, with Howell on the agenda as a presenter.

The commission’s job is to “promote the educational, cultural, economic and general welfare of the public through the preservation and protection of buildings, places and districts of historic or literary significance.”

HDC Chair Luis Berrizbeitia said the group would first take up the issue informally and then formally consider it at its December 21 meeting.

The marker matter is complex in that “some people say that they are historic because they have been [there about] 90 years… Some people say that the inconsistencies with history that these signs have are also part of our history,” Berrizbeitia said. “Other people say that it’s shameful and that it has to be changed.”

However, “there’s an entirely parallel issue,” he noted: “Obviously, there are very strong emotional perceptions about these signs, and they may become a matter of public policy for the Select Board. And if that’s the case, the Select Board doesn’t have to ask the Historic Districts Commission anything,” he said.

“If the Select Board wants to take [the signs down] tomorrow morning, they can do it [without] breaking any law,” according to Berrizbeitia. “They could say that they’re taking them out for maintenance.”