The Select Board has ordered three controversial historical signs temporarily “removed for maintenance” while the town decides their ultimate fate.

The board voted 4-1 to pull the three Tercentary markers — two in Concord Center and one on Lexington Road — after members of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and Historical Commissions argued that the signs were offensive to Indigenous people as well as historically inaccurate.

As he did with the vote earlier this month to simply cover the signs, Select Board Chair Henry Dane voted against the removal. Dane said he opposed a rush to act on the signs before further investigation.

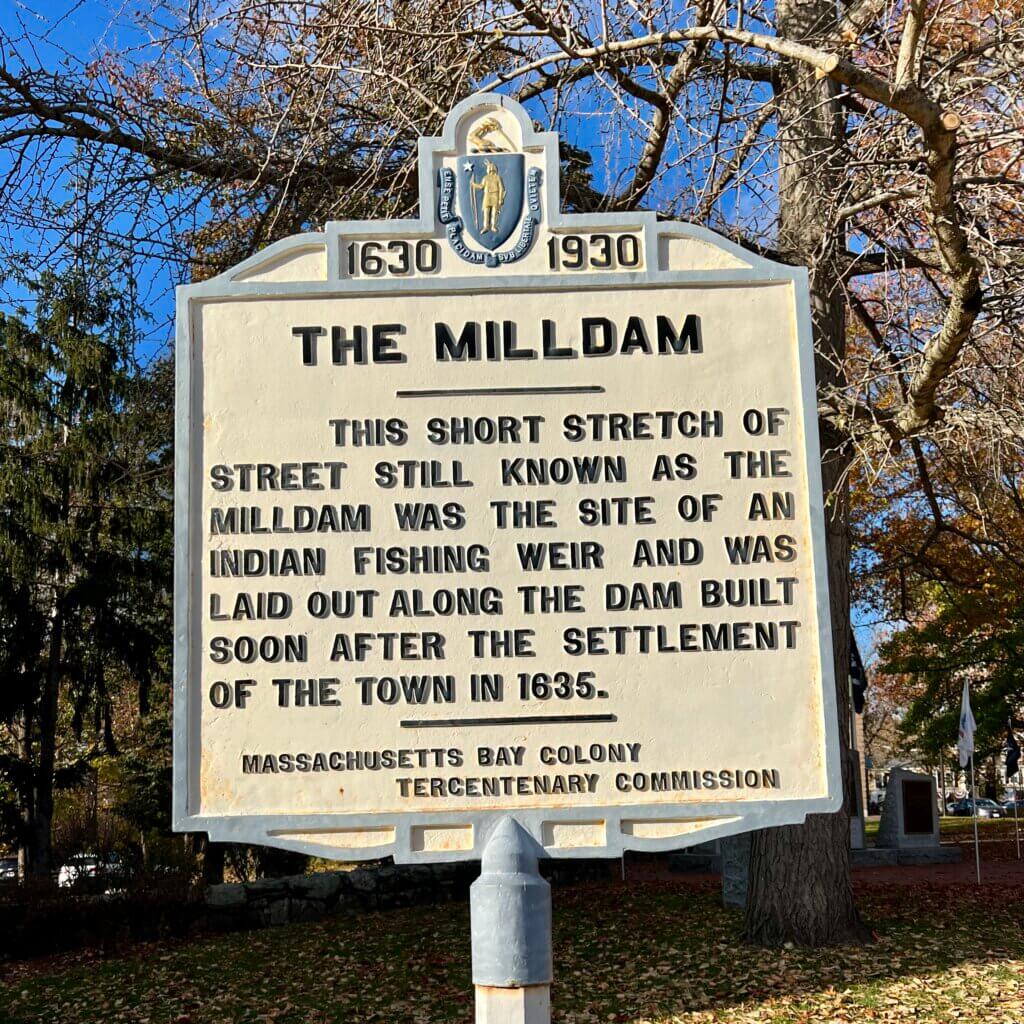

The cast-iron signs date back to 1930, the 300th anniversary of the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The Historic District Commission last week heard from Select Board member Mark Howell, who had urged his colleagues to act on the signs to stop the “ongoing harm” they cause. Howell, also the board’s liaison to the DEI Commission, told HDC it would cost about $400 to put simple covers over the signs — with or without a message on them explaining why they’re under wraps.

The HDC’s Tim Whitney asked Howell if the Select Board just voting to take down the signs hadn’t been an option. Howell said when he wrote his motion to veil the signs, he was “trying to take a light touch and not presume the outcome.” Compared to uprooting the markers, he said, cloaking them seemed like a “lesser action” that would get them out of sight while their fate is decided.

“I could see having them quote-unquote, temporarily covered — maybe with a small message saying that these are being reconsidered,” Whitney said during the informal talk at which the HDC took no action. “I read [the signs], and they just seem to be needing to be covered up. That’s just the tone of those things, if they’re really out of date.”

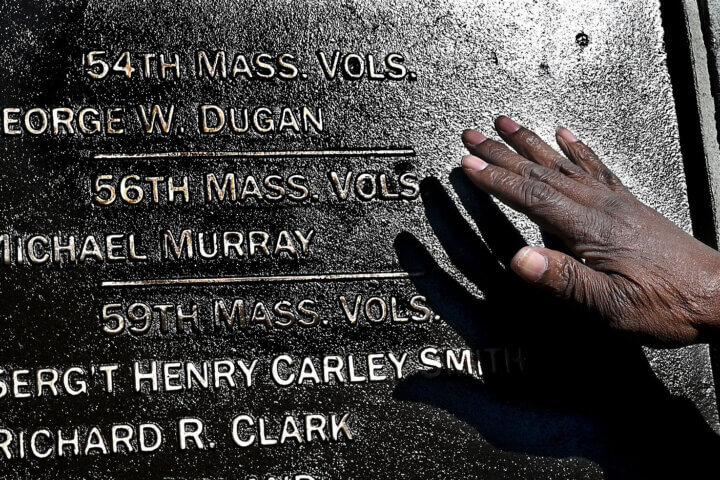

The three signs — “The Milldam,” “Jethro’s Tree” and “First Settlement” — use the term “Indian” to describe indigenous people who settled the area thousands of years before its incorporation as Concord in 1635. That’s offensive, says DEI Co-Chair Joe Palumbo, and scholars of Native history dispute that tribal representatives willingly sold colonists the “six myles of land square” that became the modern-day town.

Other “facts” on the signs are also under question, he and the Historical Commission’s Nancy Fresella-Lee told the Select Board ahead of its November 6 vote.

HDC member Dennis Fiori said he’d “go back to the Select Board and ask them just to remove it — to remove all of them. I don’t think anybody’s going to miss them. I think that the citizens rarely look at these things. They’re kind of there for tourists.”

He also advocated for digital or print guides to historic Concord sites rather than more markers: “I don’t think we want to cover the town with a lot of plaques and signs everywhere — particularly when [there are] complex stories, as this one is, with conflicting narratives and the mythic quality of it.”

And HDC member Walter Clay said his first thought “was that those who suffered the greatest offense from something like this should probably have the greatest voice in how to redress or address the situation.”

Speaking last at the November 16 meeting, HDC Chair Luis Berrrizbetia said the tercentenary markers are “irrelevant” from a historical standpoint.

When a new group of people comes to a place that’s already settled, first there’s “contact, then there’s a process of confrontation, [and] then there’s a process of cooperation,” Berrizbeitia said. “The 1930 signs are trying to idealize these difficult steps, and they are assuming [cooperation] was something that was done willingly and happily — and certainly history shows that that certainly was not the case.”

That said, the markers are a historical reference that embody “a particular view that existed in 1930,” he said, and for that reason, “I’m not certain that there’s an absolute virtue of just erasing the whole thing.”

Berrizbeitia urged that “our Native citizens be involved in this process, so at least we have a palpable perception of how offensive these signs may be.”

He added that “from a standpoint of procedure, it may have been a little premature for the Select Board — although I entirely agree with the primary purpose — to say, ‘Let’s just cover the signs.’” Any Select Board move to cover the signs “without a certificate of appropriateness by [HDC] will be a breach of our protocol and will create problems in the matter of town governance.”

Speaking at Monday’s Select Board meeting, DEI Commission Co-Chair Joe Palumbo said members of the Native community had been clear in the past on the offensive nature of such markers, and would continue to be consulted.

At the same time, he said, “It is not their burden to come to Concord and teach us to do what is right.”

Historical Commission member Nancy Fresella-Lee, who’s writing an extensive report on the markers, said she made contacts with scholars and tribal leaders at a recent conference at Harvard Radcliffe Institute on indigenous issues and is waiting to hear back from them as a follow up.

Howell said after the HDC hearing that the DEI and Historical Commissions will work on proposals for what to do with the signs, such as removing them, replacing them or working them into an educational exhibit. Based on the HDC meeting, he said, it wasn’t entirely clear whether his board could go ahead and just pull the signs rather than cover them temporarily.

Concord isn’t alone in grappling with the telling of its colonial and indigenous history.

A state commission that spent years looking at an update to the Massachusetts seal and motto just wound down without making any specific recommendations. Meanwhile, the legislature is considering bills that would prohibit Commonwealth public schools from using Native American-themed sports mascots, nicknames and logos.