Everyone knows the story of how Paul Revere rode through the night, broadcasting the alarm throughout Middlesex that the British were headed out to capture the colonists’ stores of weapons and ammunition.

Not so fast.

Not letting facts stand in the way, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow told a great and inspiring tale in Paul Revere’s Ride, creating an American hero in his poem published in 1860, on the cusp of the Civil War.

Revere played an important part in the American Revolution, but a bit different than Longfellow’s version.

In the beloved poem, as the moon rose on April 18, 1775, Revere rowed himself across the water from Boston to Charlestown, “Ready to ride and spread the alarm/Through every Middlesex village and farm, /For the country-folk to be up and to arm.”

In reality, Revere never made it to Concord, much less to all the far-flung towns in Middlesex that fateful night. He didn’t row himself either; two of his friends did.

And he wasn’t on a mission to notify the entire county. Tasked by Dr. John Warren, a prominent American leader who died during the Battle of Bunker Hill in June later that year, Revere and William Dawes, set out to separately to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock that British soldiers were headed their way to arrest them.

The two leading patriots were holed up in the Rev. Jonas Clarke’s house in Lexington, where Hancock lived for a time as a child. When Revere arrived around midnight with letters from Warren, Orderly Sargeant William Munroe initially refused to let the noisy rider in.

Accounts vary on how Revere gained admission, but he did. Munroe said once Revere identified himself, he was good to go. Other accounts say one or more of the home’s inhabitants called out to let him in.

Dawes arrived a bit later and two riders stayed for a bit, eating and drinking, before heading out to Concord.

Partway to their destination, they were joined by Dr. Samuel Prescott, a Concord physician who had been out visiting his girlfriend. Soon, a British patrol saw them. Revere was captured and questioned, the British took his horse and later released the patriot to walk back to Lexington. The other two escaped.

Which brings us to the question of how, if our legendary midnight rider was in Lexington most of the night, did the rest of Middlesex learn about the soldiers that were headed to Concord to confiscate ammunition and weaponry?

The Massachusetts patriots were an experienced and, thanks in part to Revere, organized bunch.

“Revere played a key part of constructing a network of people who would go all out,” said Concord historian and author Robert Gross, professor emeritus at UConn.

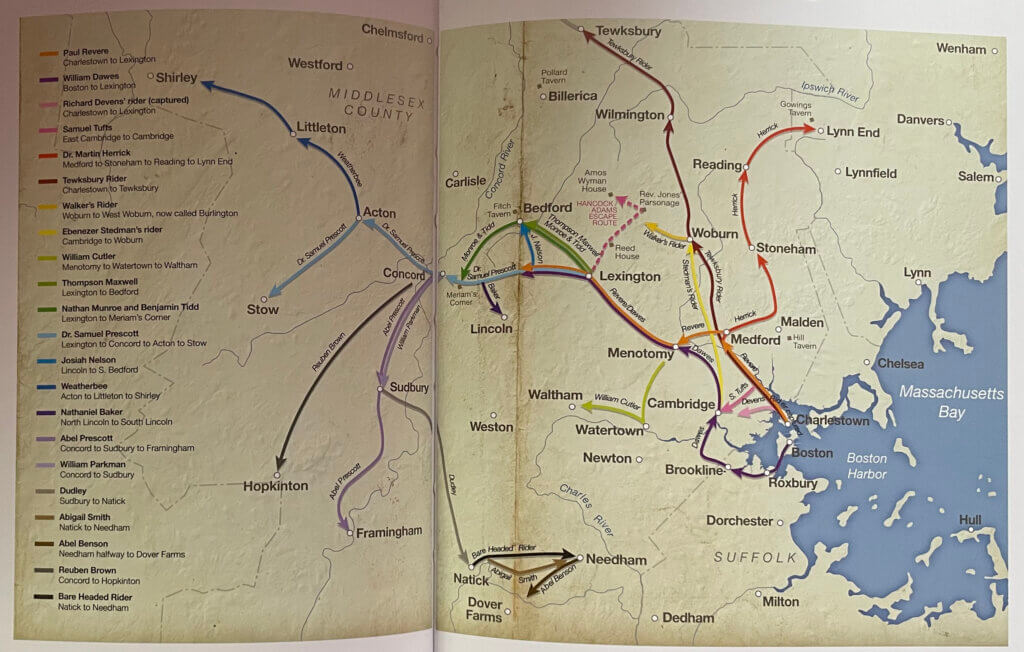

The 18th century communal network created by Revere notified the towns that the British regulars were marching out, he said. The network relied on men would ride to the next town, where another resident would carry the alarm further along. Longfellow’s Revere was an amalgamation of these local riders.

“Revere had a genius for collective action in the cause of freedom,” historian and author David Hackett Fischer wrote in a New York Times op-ed on April 18, 1994.

Signals, such as the lanterns hung in Boston’s Old North Church, played a part in sending information to far-flung parts of New England.

The colony’s alarm system was so organized, said California author Jeff Lantos, that on April 18, 1775, towns in New Hampshire knew the British were on the move even before Revere left Charlestown.

Lantos spent many summers in the Concord area researching his children’s book, “Why Longfellow Lied: The Truth About Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride,” Gross said. The map Lantos made for the book, which shows the names of riders who spread the alarm in 1775, hangs in the office at the Gross home.

In 1775, after the three riders heading from Lexington to Concord were intercepted by the British, Prescott, who was not captured, continued on to alarm Concord and other towns.

He was not the only rider to carry the alarm to Lexington’s western neighbor.

Earlier that evening, Nathan Munroe and Benjamin Tidd rode to Bedford and “to the great road at Merriam’s Corner — so called,” at the request of Lexington’s militia leader, Captain John Parker, according to Munroe’s 1824 deposition, notifying the inhabitants throughout the town.

Riders, including Prescott, left Concord to alarm other towns, spreading the word further west and south.

When they returned to Lexington, Munroe and Tidd found the bell ringing and the militia company gathering on the green, preparing for the arrival of the British, who started firing at the militiamen around 5 a.m.

Thanks to the alarm system, when the redcoats got to Concord on April 19, 1775, militias from Acton, Bedford, Lincoln and Westford, as well as Concord men, began to muster at 6 a.m., well before the 9:30 a.m. bloodshed at the North Bridge.

Around noon the British began their retreat back to Boston, hounded by Americans along the route. The battle ended around 7:30 p.m., when the British crossed Charlestown Neck, back into Boston.

Over the course of the day, an estimated 93 Americans were killed, wounded, and missing or captured. The British had 300 such casualties.

Americans were trained soldiers asked to pay for their own defense

Undoubtably, the sight of well-equipped soldiers carrying long guns put fear into the hearts of their opponents that spring morning in Concord and Lexington.

But the colonists were no strangers to military actions. Life in the New World meant that every person had a hand in keeping society safe.

Since 1628 in Salem, towns in the Bay Colony had established militias. In 1630, all adult males were required to possess guns, according to military historian Robert K. Wright.

Some colonists, including Revere and George Washington, were military veterans, having fought for the British on American and Canadian soil during the French and Indian War between 1754 and 1763.

Paying for that war become one of the causes of the American Revolution. The British Empire attempted to tax colonists to raise the money. Colonists refused to pay these taxes, first imposed in 1765, saying they had no representation in the British Parliament.

Throughout the colonies, with the word spread through newspapers and letters, residents passed resolutions refusing to pay the taxes.

Britain continued to attempt to tax goods, including tea, a favorite beverage. In 1773, Revere, along with 50 other colonists wearing “Indian garb,” dumped a boatload of tea owned by the East India Company from a ship into the harbor during the Boston Tea Party to protest new taxes.

On the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party in December 2023, a Boston Globe columnist called the action a property crime.

Another Globe article said the action was civil disobedience and inspired abolitionists, suffragists and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Sarah Palin falls for the legend

In 2011, Sarah Palin, a one-time candidate for vice president on the Republican ticket, told a story about Paul Revere warning the British which factcheck.org called not entirely wrong, but badly twisted.

The Alaskan politician provided comedians with a wealth of material when she called Revere “he who warned the British that they weren’t going to be taking away our arms, by ringing those bells.”

On April 18 and 19, 1775, Revere rang no bells and was not held long by the British who intercepted him between Lexington and Concord and took his borrowed horse.

Wikipedia, the free online, crowdsourced encyclopedia, fell prey to Palin supporters who attempted to rewrite this history, citing “well-sourced” authorities, including Palin herself, to prove she was right.

At the time, the New York Times said Palin’s implication that Revere was defending gun rights was “very much in the tradition of the telling of the Midnight Ride, which has long been used as an exercise in mythmaking.”

Impressing Lafayette

In 1824 and 1825, the only living American general from the Revolutionary War, the Marquis de Lafayette, came to the United States from his homeland in France to tour the country.

He toured 24 states and, of course, Concord and Lexington were on his itinerary.

This visit during the 50th anniversary of the American Revolution was the cause of a rivalry between Lexington and Concord, said historian Robert Gross. Lexington wanted to prove the “shot heard ‘round the world” really happened in their town. Concord was eager to prove they were the first to shoot at the British troops.

Lexington began their anniversary battle by taking depositions from the Revolutionary War soldiers who still lived. Nathan Munroe, who rode to Bedford and Merriam’s Corner, was one of those men. His account is included in the Munroe family genealogy, loaned to The Concord Bridge by a family member.

The depositions were gathered in “History of the Battle of Lexington, on the morning of the 19th April, 1775,” by Elias Phinney and quickly published in 1825.

Concord was not far behind in claiming primacy. Ezra Ripley wrote “A history of the fight at Concord, on the 19th of April, 1775” which was published in 1827.

In 2025, for the 250th anniversary, towns are working together to seek funding from the state for the celebration, which is expected to bring over 100,000 visitors.

Forgotten Revere

Thanks to Longfellow’s poem, Paul Revere is honored as a leading patriot. However, he was by no means an untarnished hero.

In 1779, as a colonel in the Massachusetts militia, the silversmith, dentist, artist and businessman was in an expedition sent to Castine, Maine, which had been seized by the British. The British beat back the American flotilla, sending patriots fleeing up the Penobscot River after burning their own flotilla.

Maine was a part of Massachusetts until 1820.

A brigadier general accused Revere of disobeying his orders.

After arriving back in Boston, Revere was placed under house arrest and investigated. The investigating committee came to no conclusions.

Two years later he was cleared by a court-martial, held at his request to clear his name.