Their time was up: Concord’s three surviving tercentenary markers were pulled up Thursday morning.

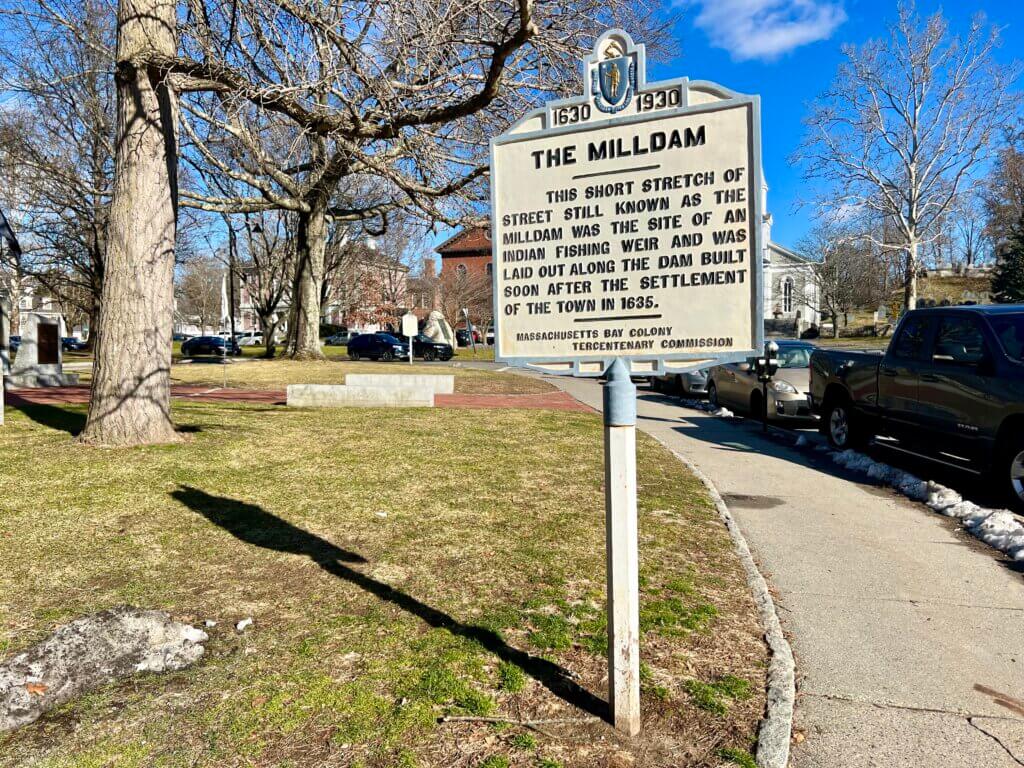

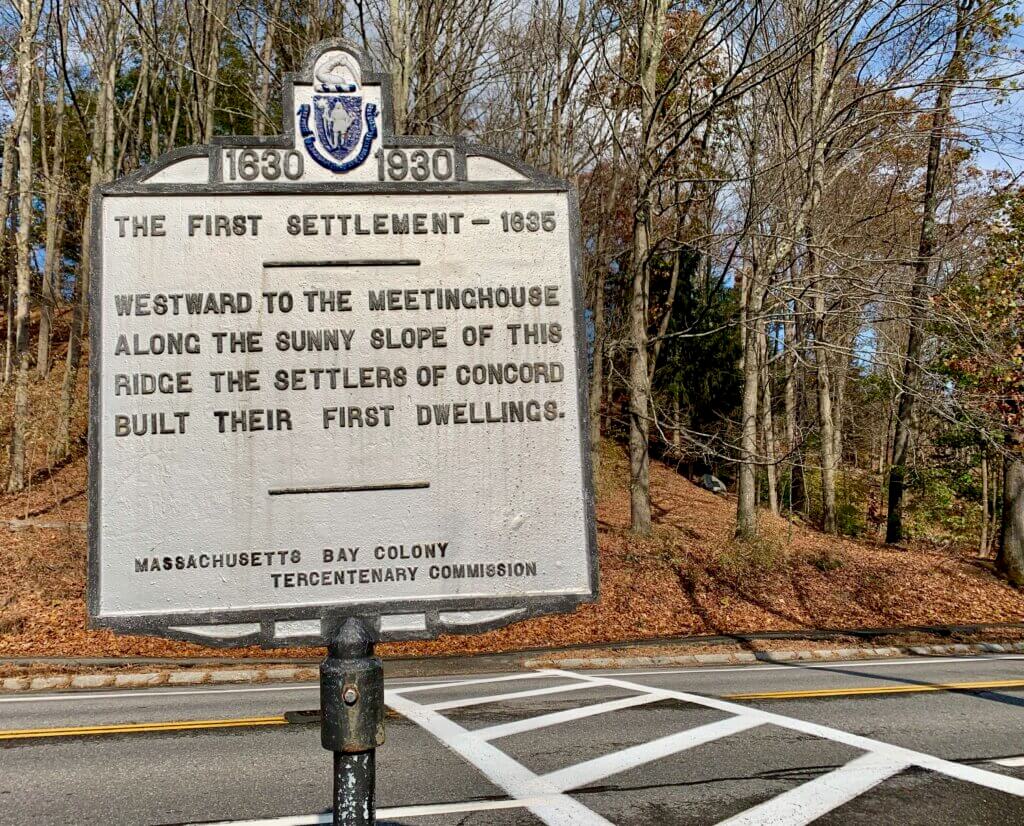

Two of the signs — “The Milldam” and “Jethro’s Tree” — were removed from Concord Center. The other, “The First Settlement,” was pulled out of its spot on Lexington Road near Orchard House.

The markers were pulled after DEI and the Historical Commission identified them as “problematic and antithetical to the inclusive goals of the Town of Concord,” said town Communications Manager Donna McIntosh in an email.

On the recommendation of the Select Board, the chairs of those commissions have “been invited to begin a conversation to discuss the interpretation and messaging on these sites, as well as a plan for the actual signs, which are period pieces,” she said.

The Select Board voted 4-1 in November to remove the signs “for maintenance” after members of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and Historical Commissions lobbied for them to go. Those members, including DEI Co-Chair Joe Palumbo and the Historical Commission’s Nancy Fresella-Lee, had called the signs historically inaccurate and offensive to Indigenous people.

Palumbo greeted the removal news with enthusiasm Thursday.

“Working together, we can continue to create ways to learn about the more complicated yet complete understanding of our past,” he said.

“Places like Concord can be at the forefront of sharing that history with the public and with ourselves. There is more to our story than is often told.,” Palumbo continued. “Telling more honest stories of the past creates an honest understanding of the present.”

The controversial-of-late signs were first placed in Concord in 1930 to mark the 300th — or tercentenary — anniversary of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s founding.

Palumbo and Fresella-Lee had argued to the Select Board that the signs were both anachronistic and inappropriate.

The markers inappropriately use the term “Indian” — rather than a specific tribal name — to describe Indigenous people who lived here thousands of years prior to the incorporation of Concord as a town by white settlers in 1635, Palumbo said.

Fresella-Lee also argued that some of the information on the signs distorts or misstates the history they purport to teach, such as the true identity of Jethro, the location of the tree and a fishing weir near today’s Concord Center, and whether Native people in fact knowingly and willingly sold white colonists the land on which they lived.

Additionally, Fresella-Lee objected to the signs’ use of the Commonwealth seal, which has been questioned and reviewed for its visual depiction of a Native man. (The seal and the Commonwealth motto were reviewed last year by a state commission which disbanded without making any specific recommendations.)

Last fall, Select Board member Mark Howell, who is also liaison to the DEI Commission, had urged his colleagues to at first cover the signs to bring a halt to the “ongoing harm” he said they presented to visitors.

Howell pushed for consulting with DEI and Historical to review options including pulling out the markers entirely, replacing them with something more “accurate” and “relevant” or incorporating them into an educational exhibit of some kind.

Only Chair Henry Dane voted against covering the signs, saying the Board should not move precipitously on artifacts that had been there nearly a century, but should consult with Indigenous scholars first.

Howell subsequently spoke to the Historic Districts Commission, which is distinct from the Historical Commission, about covering the signs.

Several members suggested they could simply be removed if the Select Board chose, including “for maintenance,” and also that people who might find the signs offensive should be included in the discussion.

“I don’t think anybody’s going to miss them,” HDC member Dennis Fiori said of the markers at a November meeting.

“I think that the citizens rarely look at these things. They’re kind of there for tourists.”

Fresella-Lee headed to the Center Thursday afternoon to check out the scene for herself. She said Concord was “setting a much-needed precedent” by removing the markers, and that the move would be “noticed and discussed” by other towns that have signs from the same program.

“The ones in Concord contain much information that is known to be inaccurate, and in some ways offensive — especially towards Native Americans. More importantly, they obscure more significant history than they reveal,” said Fresella-Lee, who wrote an extensive report on the history of the signs.

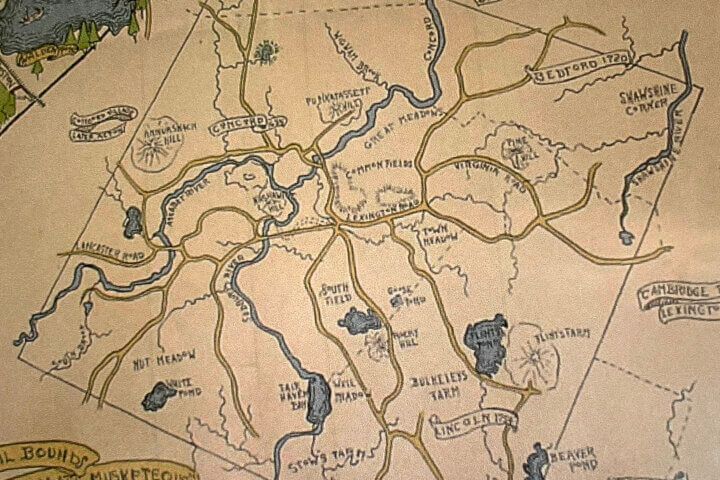

“Many people are now thinking about how to tell the stories of Musketaquid and the founding of the colonial town in an historically truthful and meaningful way,” she said. “I’m hoping we can have an educational, informed public conversation about the important issues these markers raise soon.”

Since the discussion arose, some people have expressed support for the signs — including in letters to The Concord Bridge — as themselves part of Concord’s landscape and history. Others have said the town could find more precise, appropriate and comprehensive ways to acknowledge its heritage.

Across the street from where the Milldam and Jethro’s Tree markers used to stand, Helen Denisevich got to her family’s Main Street restaurant, named for her grandmother, Helen, at about 7:30 a.m. on the Thursday morning the signs were pulled down.

She was not happy… to say the least.

“This is my grandparents’ restaurant since 1936. We as kids — and I’m 70 — would see those signs forever. And they pulled them out this morning, and I was pissed. I was gonna go over and yell at ’em,” she said.

“And I’m not the only one. I talked to other customers that came [in] here today, and they said the same thing,” Denisevich said, pausing behind the counter after the lunchtime rush.

“You know what really got me? When they took them, picked them up and threw them in the truck, slammed up the thing and left.”

Denisevich said she simply didn’t see anything offensive about the nearly century-old markers.

“I think there was no need for them to take it out,” she fumed. “It’s not going to prove a damn thing.”

A Helen’s patron, Brenda Delsener, suggested the uprooted signs could be preserved in a museum.

“Maybe cultures have changed. I think that you should still mark the passing of that transition,” she said. “I understand the thought process behind it, and it’s one of those things like, ‘How come we didn’t think of that before?’ But still, there is a certain sentimentality to just the presence of the history.”

The Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentenary Commission put out a total of 275 cast-iron markers in 1930 to commemorate the anniversary across the Commonwealth. Marking spots of historical interest, they were deliberately made to be clearly legible from a moving car as automobile travel became more popular.

Nearly 100 years later, some of those markers remain while others have found their way into storage or have even reportedly been spotted at junkyards.

The call to take out the signs “was a hasty and ill-considered decision, but the removal is not the end of the matter,” the Select Board’s Dane said Sunday.

“The deputy town manager is working on convening a meeting of interested parties to see where we go from here. This is what should have happened before, not after, the signs were removed.”