Last year, one person died of an opioid overdose in Concord.

The year before, Concord Police responded to five opioid overdoses.

Naloxone, marketed as Narcan, can pull an overdosing person back from the brink. It’s now available free at the town offices at 141 Keyes Road and will soon be at Concord libraries.

Concord’s public health nurse, Moira Carter, notes that the rate of opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts grew 3% on average from 2015 to 2022, per state data released in December that showed more than 2,300 such deaths in 2022.

With opioid drug deaths in the news, mainly thanks to fatalities associated with fentanyl, a synthetic that’s up to 50 times more powerful than heroin, “I think much of the community is very aware [of] those significant numbers and that rise in [opioid] use and in fatal overdose deaths,” Carter said.

Concord Police Department Captain Brian Goldman said in his estimation, for the town, “I wouldn’t say it’s a huge problem or a little problem. I think it’s a problem that affects everyone everywhere on some level…

“The movement here in Concord is to make Narcan [available as] a proactive step,” Goldman said. “I think it’s fair to say we don’t have the same issues [that] Boston has … to try and say we don’t have it at all isn’t accurate either.”

Distributing a livesaver

In an overdose, opioids, which affect the brain and spinal cord to reduce the perception of pain, can slow breathing to the point of death. Naloxone can stop the effects of opioids such as morphine, codeine, heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, fentanyl and methadone.

“Even before I came on board as public health nurse in the fall, [Health Director] Melanie Dineen became aware of the community naloxone program and initiated that process of Concord being a participant in that program,” Carter said.

In the fall, the town worked with the Great Meadows Public Health Collaborative “and got some of our initial Narcan supply and trainings.” Town employees had a chance to learn about the anti-overdose treatment, and Concord distributed about 30 boxes — 60 doses — of Narcan.

As of late January, an additional 18 boxes, or 36 doses, had been picked up from Keyes Road, said Carter, adding that if local businesses are interested in training or being Narcan pick-up locations, she hopes to hear from them.

Narcan is “safe, easy to administer, [and] has no potential for abuse, which makes it such a helpful tool,” said Carter, who recommends having doses on hand to “any person who is using an opioid, or [anyone] in the community who wants to be prepared if a loved one or anyone near them suffers from an overdose.”

Help — without fear

Despite efforts to speak more openly and acceptingly about drug abuse as well as mental health issues, “there is a lot of stigma,” Carter said.

For that reason, she said, it’s critical to consider people who may be at risk of overdose — or who care for someone at risk — but feel that stigma. Importantly, at Keyes Road, “anyone can come in” to pick up a box of Narcan nasal spray on the second floor “and doesn’t necessarily have to interact with [anyone],” she said.

Emily Black, a clinical coordinator and outreach clinician who works with the Concord, Carlisle and Maynard Police, said it’s crucial for people to understand that if they call for emergency help in an overdose situation, they’re generally not at risk of facing charges over the drugs involved.

“There’s no criminal attachment to it. There’s no stigma to it. If people need Narcan, we will supply that,” she said.

Agreed Goldman, who says the police have carried naloxone for about the last eight years: “We’re there to get you the help … For O.D.s, we don’t go investigate. We treat that as a medical; we don’t treat that as something that we look at towards trying to charge someone with a crime … That changed in the law several years ago.”

Of the five opioid-specific cases Concord logged in 2022, Black believes Narcan was administered in all of them — including, in one case, by the person who called in the overdose. Two involved Concord residents; the other three were visitors or just passing through.

The person who died in 2023 was not from Concord and was an “at-risk” individual known to police, Goldman said, adding that it was not entirely clear whether the overdose was accidental or intentional. The Concord Bridge has made a records request for the police report associated with the death.

Keeping Narcan within reach

Commonwealth law requires retail pharmacies to stock naloxone.

But as a January Boston Globe survey of more than 60 Massachusetts pharmacies found, that’s not often the case: Many drugstores either don’t stock it, have it but keep it locked up or tucked away, or wrongly say a prescription is necessary for the over-the-counter treatment.

Carter said for those who are new to it, “the Concord Health Division invites and encourages — but does not require — those who are seeking Narcan to meet with me for support, [to] review what resources are available to that person or their loved ones,” or just ask questions.

Additionally, Carter said, there’s always information available at mass.gov/narcan. And at 141 Keyes, next to the Narcan packs, there are wallet cards with basic instructions “for recognizing and reversing an overdose using naloxone.”

Goldman said he’d like to think there’s been some progress made on addressing the opioid epidemic.

“Back [in] 2016, 2017, even going into ’18, [this] was a big problem across the country. And there were a lot of fentanyl overdoses that were taking place, heroin overdoses back then. And there was a lot of awareness and a lot of things put out, and obviously Narcan was implemented and given to the police officers. [So] I’d like to think we’ve come a long way since then,” he said.

But Concord’s progress on one issue can leave many others to grapple with: “These calls have been decreasing while other mental health-related calls have been skyrocketing,” Black said.

“I would say we lost many more lives to suicide last year than we did to O.D.”

FAST FACTS:

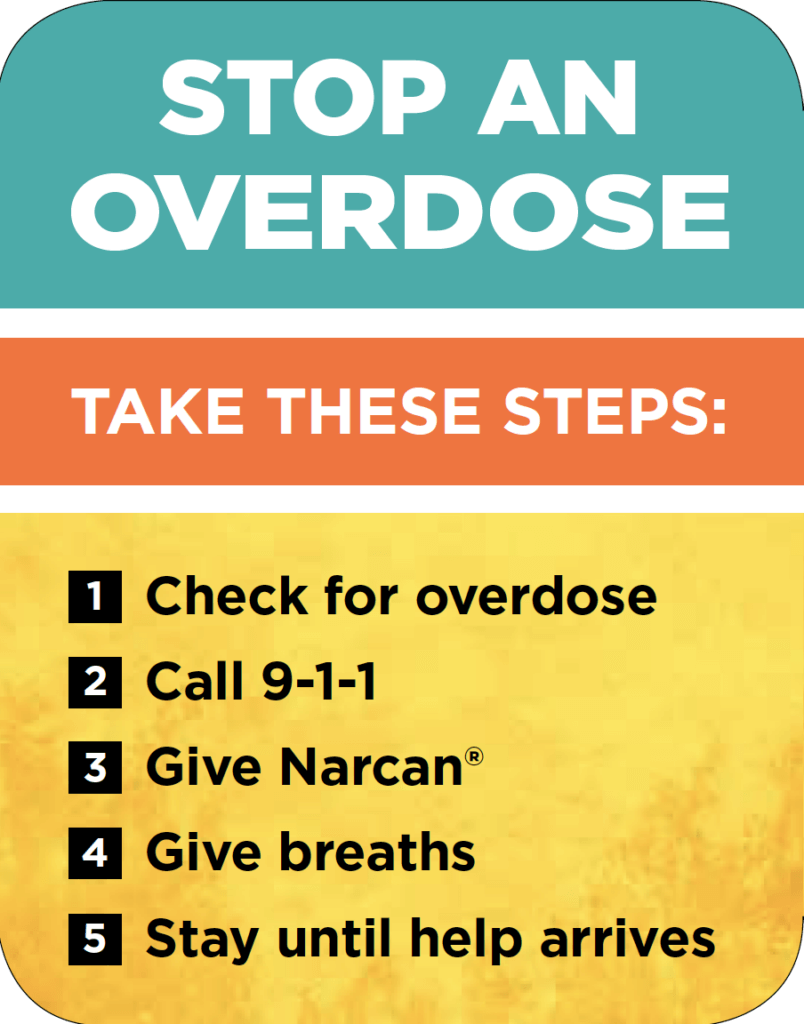

Here’s what the Massachusetts Department of Health and Social Services says you should do if you need to administer naloxone to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose:

- Check for signs of an overdose by speaking to the person and vigorously rubbing their chest. If they don’t respond, it may be an overdose.

- Call 911 and report if the person isn’t breathing or might have overdosed.

- Place the tip of the Narcan spray into the nostril of the person who overdosed. Push the pump to release the dose.

- If you can, assist the person by giving rescue breaths (ideally with a bag-valve mask, but if not, mouth-to-mouth).

- If the person doesn’t appear to be responding to the Narcan, give another dose every three minutes, switching nostrils with each dose.

- Once the person breathes well on their own, place them in the “recovery position” by rolling them onto one side with their opposite hand supporting their head and bending their knee to keep them from rolling onto their stomach.

- Keep going with Narcan and/or breathing assistance until help arrives — unless you must leave for your own safety.