By Christine M. Quirk — Christine@theconcordbridge.org

Osamagbe Osagie speaks fondly of her time facilitating a Wednesday night reading group at MCI-Concord. She and a group of men read poems and texts and discussed them, and the men were encouraged to share their own writing with others.

“It was a wonderful sense of community,” she said. “We found materials that were accessible for all reading levels but had depth. … The conversations were so rich.”

Osagie’s group ended abruptly during the pandemic, and she had been looking forward to resuming it. But the Department of Corrections was slow to reintroduce volunteers, and now that won’t happen at all, at least not at the Concord facility, where the inmates are on their way out.

“I miss it deeply,” she said.

One-on-one work

Osagie is one of dozens of volunteers who, through Concord Prison Outreach, provide behind-the-wall mentorship and support to the incarcerated. The organization has expanded to provide services in nine other facilities in central and eastern Massachusetts, but it was founded in Concord in 1968.

“It really started when there was more of a partnership with the town and the prison,” Board President Liz Rust said.

In the early years, she said, the institution was a visible part of the community. The superintendent marched in town parades, and the correctional officers lived on Commonwealth Avenue.

Though the demographics of the prison changed after World War II, the commitment of the volunteers did not. CPO was entirely volunteer-run until seven years ago when it hired its first director.

“What’s unique is the core of volunteers,” Rust said. “They do all the programming in the facilities.”

Ellen Quackenbush worked with inmates through the Tufts University Prison Initiative and mentored a student working on a liberal arts degree. He was researching agriculture in South America.

“I’d talk to him about what he was going to write and help him with research he didn’t have access to,” Quackenbush said. “I’ve done a lot of social justice work, but I think that these types of programs, working one on one, is especially rewarding.”

The idea of going into a prison may be daunting for some, but Quackenbush said it’s easy to adjust.

“You go through a metal detector and iron gates, but then you get used to it, and you think, ‘Oh, it’s just like TSA at Logan,’” she said.

Rust said both inmates and volunteers only use first names and offer no identifying information. Relationships outside of the wall are prohibited, but that doesn’t mean there can’t be a meaningful connection.

“Sometimes it’s clear you’ve made an impact in someone’s life,” Rust said. “It’s a very stark situation in prison, and if you’re motivated to help someone in that situation, it’s a very deep experience.”

Quackenbush said her mentee didn’t stay in the program long, but she still thinks of him.

“I think the connections that are formed are real,” she said. “I’m sorry that kid didn’t stay in the program, because I liked him.”

‘You have to listen to someone’s story’

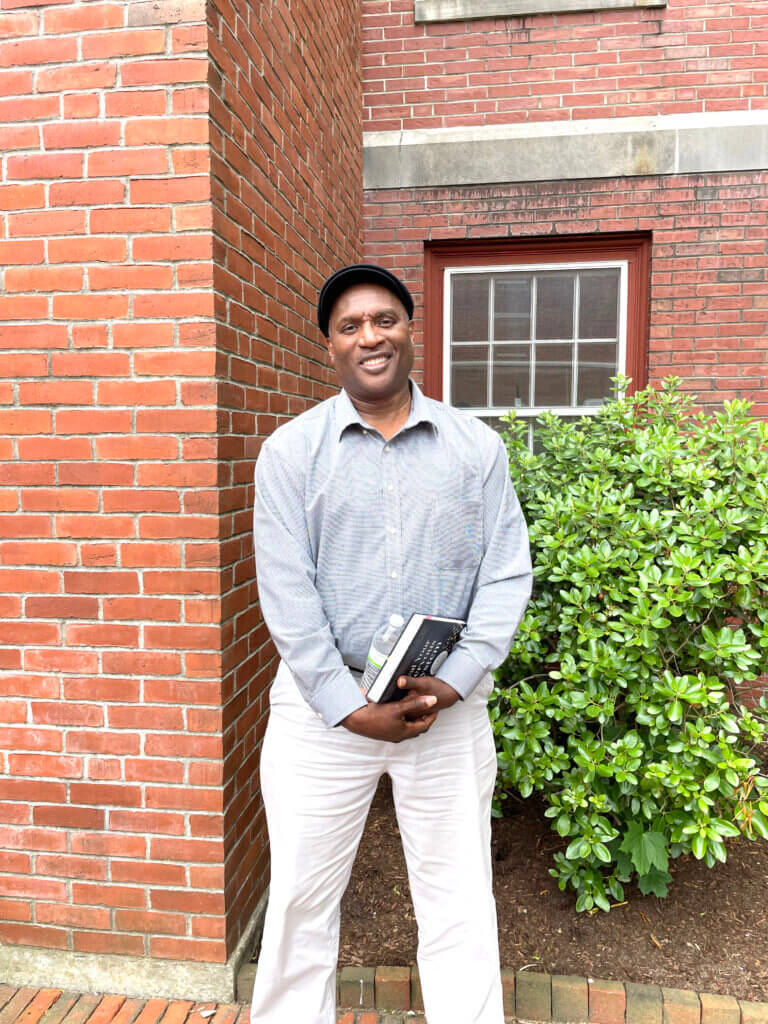

Sam Williams, CPO’s current director, has been doing reentry work for 28 years, and many of the men have stuck with him. He spoke of Tommy, who was incarcerated as a young man, released, and ultimately came back to prison on a murder charge. He is 83 years old and, all told, has spent 60 years behind bars.

Then there’s Stevie, who was surrendered into foster care by his father. He spent half of his 30-year sentence in solitary confinement and as a result, he’s sensitive to loud noises, including the prison intercom and the television.

Stevie is weeks away from being released, and recently, his long-term girlfriend told him she had met someone else.

“I know that what he’s experiencing is the present, but it’s also a deeply core triggering pain that goes back to what caused him to be in foster care,” Williams said. “The little boy in Stevie is now the man who is being walked away from.”

These stories are not unique, Williams said; there are many root causes of criminal behavior, including abuse, addiction, and mental illness. When people suffer as children, both Rust and Williams said, the cycle continues as they grow into adults.

This is one important aspect of the volunteer work, Rust said: To help people both inside and outside the walls understand the humanity of the inmates.

“You go in and do this work, and these people, they’re just people,” she said.

Quackenbush agreed.

“You have to listen to someone’s story,” Quackenbush said. “The data is great, but the stories are what change people’s minds.”

Though Concord is closing, the work goes on.

“Some volunteers who live in Concord might not want to go to Gardner or Shirley,” Williams said. “If there’s an impact, it’s that. How are we going to get folks to stay excited, if they are going in, and if not, how will we attract new excitement in these local areas?”

Quackenbush plans to volunteer at MCI-Framingham, and Osagie hopes to find another facility.

“I cannot go to MCI-Concord anymore, so I have to find another space to do this work,” Osagie said.

“I don’t know what that will look like and what that would be, but I do hope I can do that somewhere.”

Said Rust, “Our goal and our commitment is to keep it running for another 50 years… This work doesn’t go away.”