By Luke McCrory — Correspondent

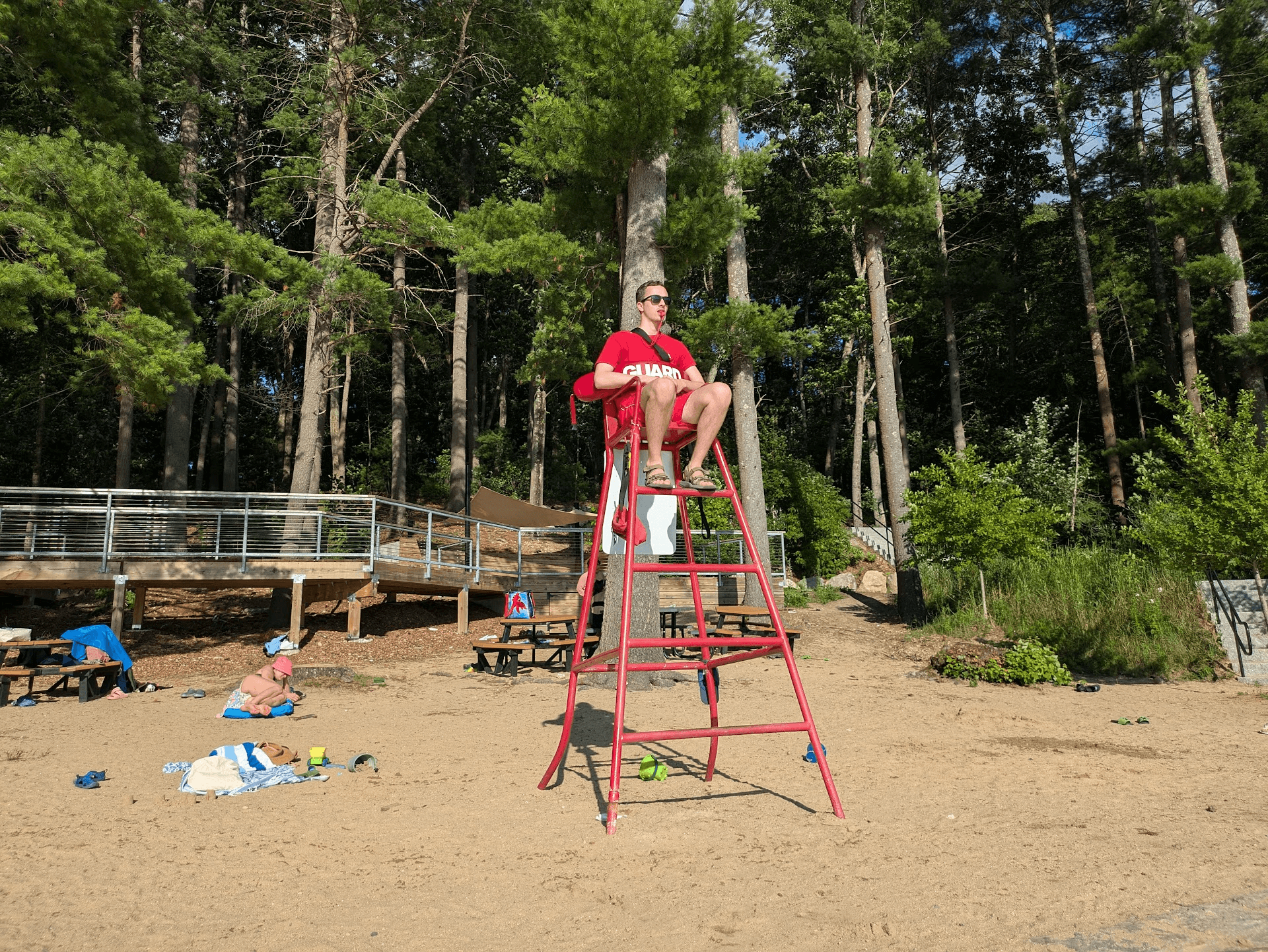

When I’m not writing articles for you to read in The Concord Bridge, I’m a lifeguard with the Town of Concord, which oversees swimming at the Beede Center, White Pond, and Emerson Pool.

Pop culture has long lampooned lifeguards as slackers who spend a lot of time lounging around, staring into the distance, twirling their whistles, or chatting it up with colleagues and beachgoers.

Sure, there’s some of that, but in reality, behind every pool and beach day stand a slew of critical training regimens, certifications, skills, and maintenance tasks that are often invisible to the swimming public.

More than anything, there’s the looming possibility of springing to action to save a life.

I never really considered being a lifeguard until the opportunity presented itself when I worked at a summer camp two years ago. I knew I was quick on my feet and loved being outside and on the water, whether it was a lake, pond, or pool.

Why not give it a shot? How hard could it be?

It was more involved than I expected.

Put to the test(s)

Before taking the stand, every lifeguard must get a two-year certification from the Red Cross that covers physical fitness and swim technique, in-water rescues, first aid, and CPR.

More than 20 hours of online modules and pop quizzes drill candidates on the rigors of being on the stand, equipment they must know how to use, and emergency scenarios that require a lightning-fast reaction time and instant recall of unique action plans.

Want to become a lifeguard? Better hope you pass the written test at the end of the course.

There are different rescue protocols for a responsive victim, one whose face is underwater, and someone with a spinal or head injury. Infants and toddlers get specific types of CPR.

Applying the right skills at the right moment can be the difference between minor and major injury — or even life and death.

All of this knowledge is put to the test in the physical trials that determine if you’re fit for the job.

Swimming ability is paramount, of course. I had to swim 400 yards in under eight minutes, then immediately swim out and retrieve a ten-pound weight from the bottom of the seven-foot-deep lap pool and return it to shore in 90 seconds. Lastly, I had to tread water with only my legs for two minutes (as my arms would be busy during a rescue).

Then, an instructor simulates numerous extrication situations — and they’re timed. Multiple victims. Unconscious victims. Sinking victims.

Mix up the order of the steps? Forget something?

You’re getting back in the pool to do it again — and probably getting yelled at along the way.

Meet the expectations, and you finally take a stand and get paid to protect swimmers’ lives. For the next two years, until recertification, we must have all of this information on file in our heads at a moment’s notice, with the highest of stakes for failure.

Not such a cushy job after all, right?

Besides scanning the Beede pool, we must manage chemical levels in the water and have basic knowledge of the systems in the “staff only” rooms.

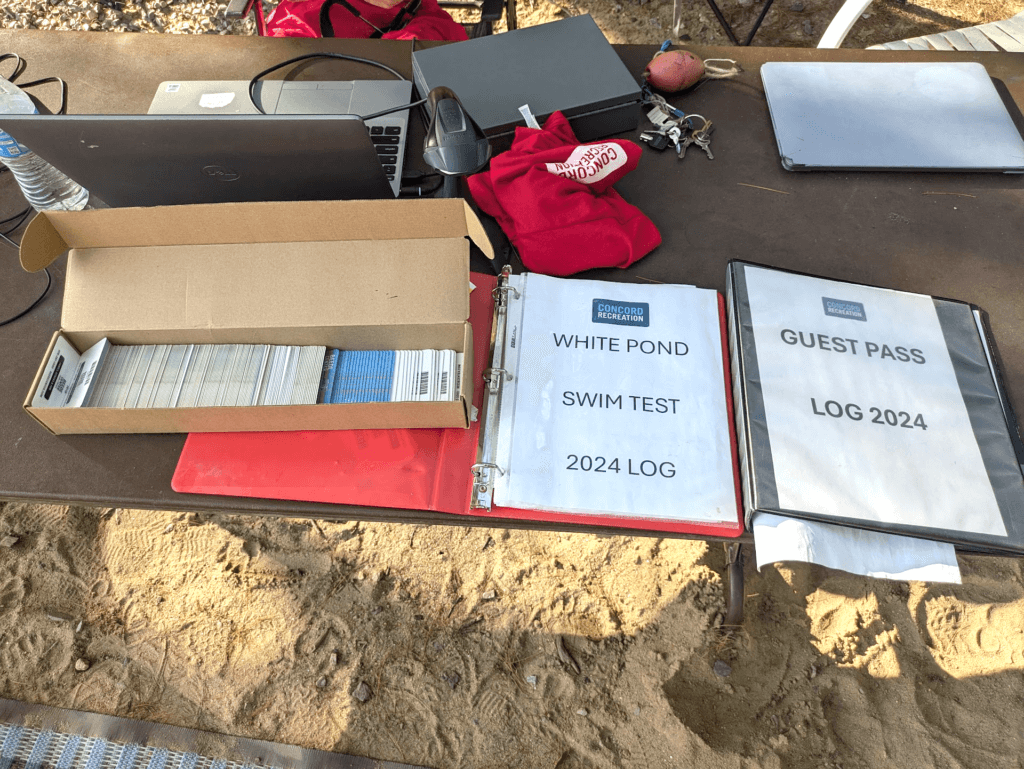

For work at White Pond, there’s an extra “waterfront” certification each lifeguard must hold. It involves the same skills used to guard a regular pool — with the added responsibility of working in deep water and using a rescue paddleboard if needed.

Advice from the stand

On a day-to-day basis, Concord’s good swimmers significantly lessen the risk of an emergency. That helps lifeguards breathe out a bit, and we appreciate that.

Here’s what you should remember to make my job and your swimming experience safer — and avoid a worst-case scenario, like the one we recently saw at Walden Pond:

- Know your skills, and your limits, in the water.

- Always, always, always bring a buoy or other flotation device when swimming in open water, such as at White Pond or Walden. Seriously.

- And please, never swim alone.