By Ken Anderson — Columnist

The other day I watched a procession of antique cars heading west on Main Street. I saw a couple of hot rods (1932 Ford coupes made into teacup cars with enormous engines and big back tires), a 1950 (or 1949) Ford coupe (it wasn’t a 1951 because it had one bullet in its grill, not two), two T-bird convertibles, and a 1964 Chevy Impala, among others.

Cars were a vital part of our lives when we were growing up. When I was 9 or 10, Ford came out with the Thunderbird. At the Ford dealership on Walden Street we got T-shirts and plastic model kits based on the Thunderbird.

I wasn’t that impressed. We were a Chevy family, and we scarcely knew any Chrysler families.

(Besides, didn’t “Ford” stand for “Fix On Road Daily?”)

In high school we became more in tune with cars. We dreamed of cars so we could go parking… and racing.

Of 409s and Mustangs

I had a friend whose family had a 1963 Chevy 409 that could burn a long stretch of rubber. He rotated the tires regularly. His car was a good match with another friend who drove his family’s 1962 Pontiac LeMans with a 326 cubic inch engine and a standard transmission on the floor.

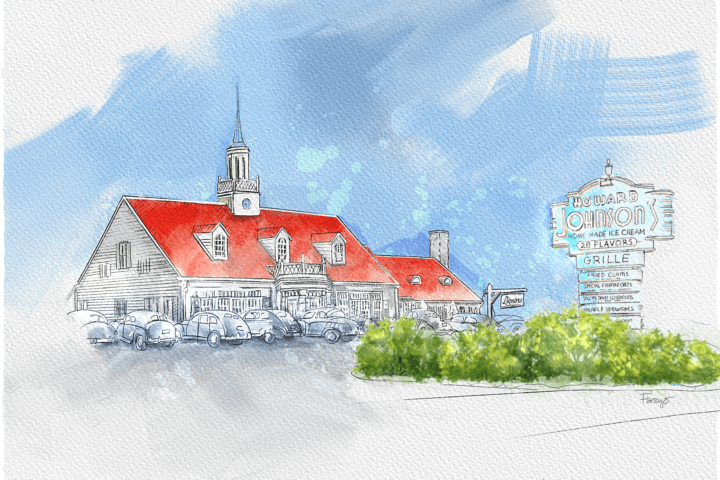

Some readers may remember car hop places, most likely from movies placed in Southern California. But there was one in the vacant lot across from the Alewife T station when we were in high school. If you were looking for a drag race, you would circle the lot until a car gave a signal. Both cars would exit and go to the traffic light westbound on Route 2. There was a straightaway, at least a quarter mile, and the cars would race when the light changed.

My 409 friend’s father also had an early Ford Mustang. One day, we went to a speed shop (selling not drugs, but things to make your car go faster), where he bought a dual carburetor, a full race camshaft, and exhaust system cutouts. We got to work in their garage: The hood was up, the grill was off, and the front and top of the engine were removed. His mother walked through the garage and asked him if his father knew what he was doing. My friend assured her that he wouldn’t mind. I am sure the car went faster, and I know that it sounded great when the cutouts were open.

Our family was given a 1946 or 1947 Ford station wagon, a woodie, albeit with some rotted wood. My friend of the 326 Pontiac lived next door to two brothers who were gearheads and hung at Crosby’s station, working on cars. We put our heads together and decided that the woodie needed a floor-shifting transmission rather than the sedate column shift. All we needed was a transmission case and the appropriate gears to put into it. I forget where we got the case, a ’39 transmission, but there were two junkyards in Westford where we could get the transmission innards. Ford transmissions were basically the same for many years, both in Fords and Mercurys.

Who needs second gear?

We encountered some logistical problems. The floor “boards” were one piece of metal that ran from the driver’s door to the passenger’s door. We removed it and cut a hole for the transmission. Second gear bumped into the space heater, so we had to take it out. It was late summer, and wasn’t a woodie a beach car anyway?

We put the car together and took it out for a test drive. It locked in third gear. We made it home without burning out the clutch. For a while we drove it without the floor board but with socket wrenches so we could remove the cover, kick it out of third gear, adjust the gear levers, and put the top back on.

All was fine until one morning, with my brother and Harold Goranson with me, about 50 feet out of our driveway, the differential disintegrated. Differentials were not easily found, so that was that.

A Mercury in retrograde

The other car I had in high school was a 1955 Mercury convertible with a Hurst conversion kit (to shift gears on the floor, not the column), lake pipes, a front end seriously out of alignment, and little oil in the transmission. The transmission soon froze up but (see above) transmissions were easily found. For some reason, I had to replace the transmission one or two other times and developed a procedure for changing transmissions — which came in handy later.

By “later,” I mean freshman year in college when speech class was required. We had to give a number of different speeches. Luckily, one speech was a demonstration speech. I brought out a chalkboard and went through the procedure. Happily, I got one of my best grades in college… but probably didn’t convince any classmates to switch their majors from pre-med to auto-engine repair.