By Jack Brox McCarthy

If you’ve read anything online about Japan, you’ve almost certainly run into some discussion surrounding the phenomenon of Japanese mascot characters. If you’re a John Oliver fan, there’s a decent chance you’ve heard his discussion of the otter mascot Chittan, who appeared in a 2019 episode of Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight.” There are animal mascots, monster mascots, anthropomorphic food mascots … You name it, Japan has a mascot for it.

If I were to editorialize, I might say that the Japanese mascot discussion on the American internet sometimes slips dangerously into the realm of “Oh, Japan, isn’t it so quirky!” It’s the same mentality that spawns articles like “Top 10 Strangest Vending Machines In Japan! You Won’t Believe #9!”

If I were to keep editorializing, I would say that this kind of thing falls into the category of tourism-as-spectacle as opposed to tourism-as-understanding. And if I were to editorialize even further, I might say that as the same nation that produced Wally the Green Monster, we don’t really have a fluffy green leg to stand on when it comes to weird mascots.

Anthropomorphic sushi

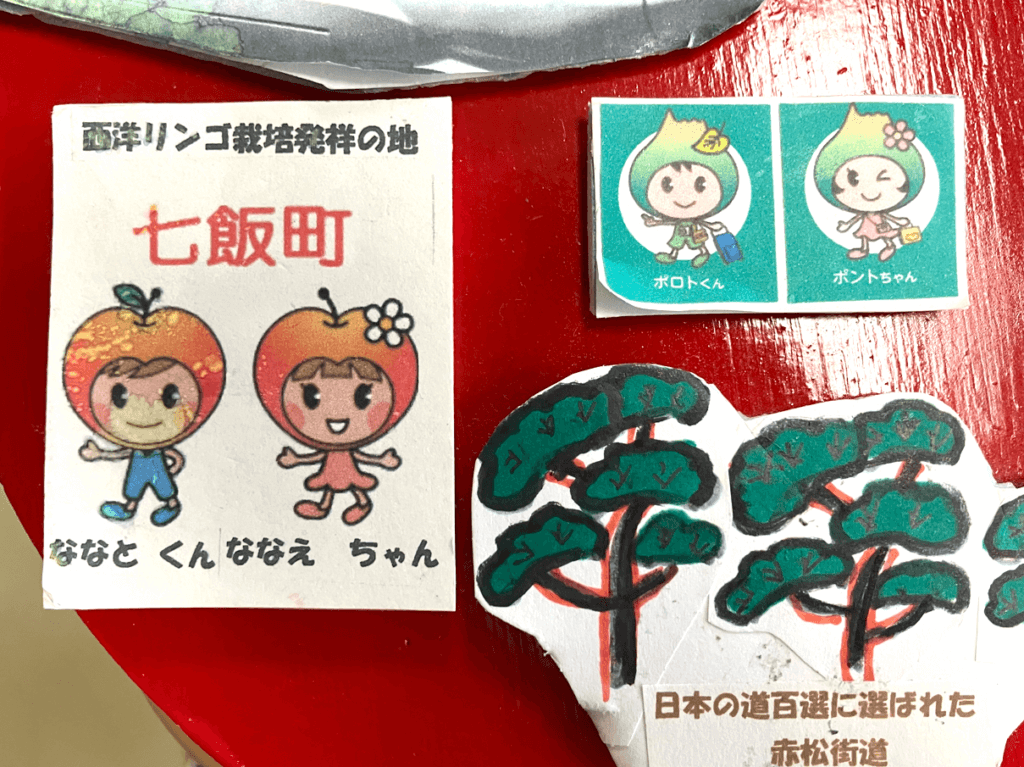

If you’re looking for them, the Donan Valley — the area around Concord’s sister city, Nanae — has plenty of iconic characters.

Next door in Hokuto City, there is the infamous Zushihoky, a wild-eyed piece of anthropomorphic sushi.

Hakodate also sells one of Hokkaido’s unofficial mascots: Melon Kuma! Half-melon, half-bear.

Nanae has Poroto-kun and Ponto-chan. Their names actually come from the Ainu words for the two halves of Lake Onuma. In Nanae, Lake Onuma is our Walden Pond — a body of water that looms large physically and culturally in a small town.

I first came to Nanae with the program as a high school student, and when I returned as an adult, I had only a dim memory of the twin mascots. One day two summers ago, sitting in the car with my boss, I asked her:

“What are those two vegetable mascots again?”

“Vegetables?”

“Yeah, they’re, like, onions or something … ”

She couldn’t help but laugh.

“They’re not onions, Jack. It’s supposed to be Mount Komagatake.” (Mount Komagatake is the volcano that rises behind Lake Onuma.)

Now, I know you’re thinking: “Jack, that’s not so bad.” Just wait.

A ‘silly American’ story

My boss couldn’t stop laughing, and it became a great “silly American” story to have in the quiver.

But one day, recounting the story to an artist friend of mine, I couldn’t help but notice her get progressively more forlorn. Finally, she exclaimed: “No! Not moldy onions!” She wasn’t just an artist — she was the artist who first designed the mascots!

When you’re looking at the mountain, the comparison becomes undeniable. She did her job well; I’m just a little slow.

The names Poroto-kun and Ponto-chan bear more thought. The relationship between Japan and the Ainu is, like the relationship between America and our Indigenous populations, fraught … to say the least. And in Japan, as in Massachusetts, a passing glance can give the impression that Indigenous names are all that remain.

But as it is sometimes said in movements around preserving Native American culture, and among Wampanoag efforts especially, “We still live here.”

In Hokkaido, you can actually see the Ainu language on a map. Hokkaido’s most famous ski resort, Niseko, has an Ainu name. And even just looking at it, you can tell it’s different. Japanese has three alphabets: kanji (reused Chinese characters), hiragana (a phonetic alphabet), and katakana (a second, more simple, phonetic alphabet). As any first-semester Japanese student would be happy to tell you, the visually stark katakana alphabet is used for non-Japanese — foreign — words. Common examples include words like コーヒー and コーラ (coffee and cola, respectively). Many Ainu names are presented in this script.

Reviving Ainu culture

I don’t mean to leave an overly bleak impression. While there is still work to be done, year by year, there is more and more recognition of Ainu culture in Japan. This living presence is essential. And the Ainu language, too, has a living component, more so than other languages. Part of the reason we use katakana is not only for cultural demarcation but also because there is no written alphabet for the Ainu language.

In a truly fascinating cultural preservation project, NINJAL (the National Institute of Japanese Language and Linguistics), has created an online repository for fully glossed Ainu folktales, all of them read aloud and recorded, all with the hope that it will be “useful to the Ainu people who are now in the process of revitalizing their language and culture.” It’s worth a gander if you’re interested.

So much, so fast

It was a long walk from Zushihoky to here. I only hope it felt meaningful.

The mascots in Japan can be goofy just as easily as ours can be in America. Yet when I started asking questions about how they came to be, it took me far, far away from the cartoon characters and into the real history of my adopted Japanese hometown.

We don’t use the names Poroto and Ponto for Lake Onuma anymore; we say Onuma and Konuma. Those Ainu words now live on most strongly with the mascots.

But while I was doing cursory research for this piece, I found out that Lake Onuma was formed by a volcanic eruption 20 years after the Mayflower landed in what would become America. The attempts to preserve and save the Ainu language are touched by an air of desperation — yet so recently it was still strong enough to be naming new natural phenomena that appeared in the world.

How could it be for so much to happen so fast?

Inquiring minds in Nanae want to know

My co-workers sometimes ask me if Concord has a mascot. Obviously, there is the minute man, but if you were to make a Concord mascot in the style of some of the Japanese characters, what would they be like?

Email jackbm.in.japan@gmail.com with any questions or recommendations.