By Christine M. Quirk — Christine@concordbridge.org

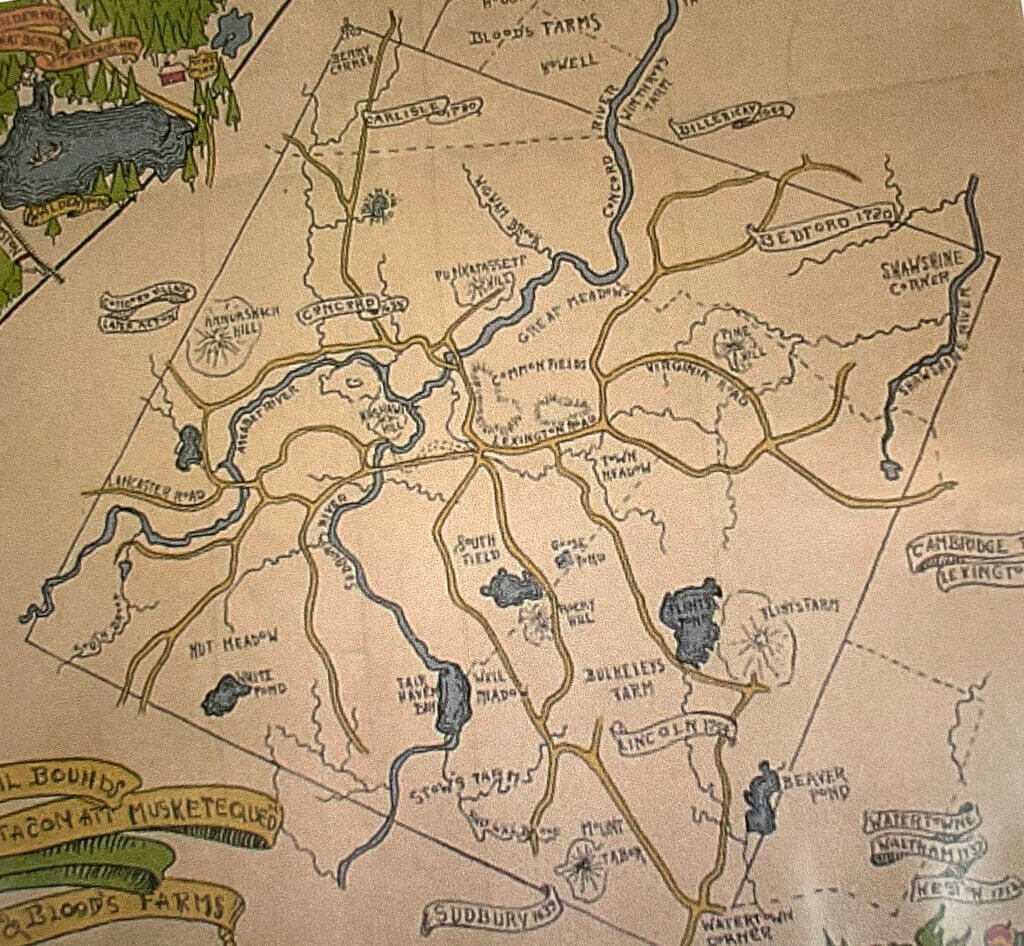

Concord is known for the “shot heard round the world,” but the town was born more than a century before, on September 12, 1635, when the Massachusetts General Court granted permission to build a settlement there and 12 families began a community.

Concord Visitors Center tour guide Jeff Driscoll helped celebrate the 389th anniversary with a 90-minute guided tour around the center, spanning prehistoric times through the 19th century.

Driscoll talked about King Philip’s War, the French and Indian War, and, of course, the American Revolution, but most of his stories detailed the lives of those who lived here.

Diane Fulman, who said she has lived in Concord for “many years,” took notes as Driscoll talked. “It’s a good thumbnail sketch of what Concord is all about,” she said.

Musketaquid

The area was first called Musketaquid, which means “land along the grassy river,” when it was settled by Indigenous people. They cleared the land and grew “three sisters crops” — corn, beans, and squash.

“The myth was that the idea for settling down and growing things would come from a crow, and the crow would come back every year to get its fair share,” Driscoll said.

Colonist Simon Willard was drawn to the area due to the cleared land and ample water. The new settlement was named Concord (“peaceful agreement”). Written history says that within two years, the English had formalized their ownership of the 6-square-mile town by trading tools and textiles beneath Jethro’s Tree near what is now Wright Tavern.

However, in recent years, it has been argued this was more a takeover than a transaction. In 2023, signs marking that spot and two others were ordered removed by the Select Board amid what critics pointed to as offensive language and historical inaccuracies.

The English also brought illnesses from which the Native people had no defense.

“Historians estimate that 90 percent of Indigenous people in Massachusetts died from disease,” Driscoll said.

Building the Center

Early settlers dammed up Mill Brook to form the Millpond; the water flows under the sidewalks and is visible from 37 Main Street’s back window.

The pond was drained in the early 1820s as Concord was preparing for the 50th anniversary of the Revolution in 1825 and taking steps to beautify the area.

“They got rid of some of the noisy, smelly businesses that had developed as a result of the dam,” Driscoll said.

Those businesses, such as a grist mill and a blacksmithery, were moved to West Concord. Town leaders then “put in some less obtrusive, less smelly businesses … like shoemakers” downtown.

The footprint of that renovation remains today.

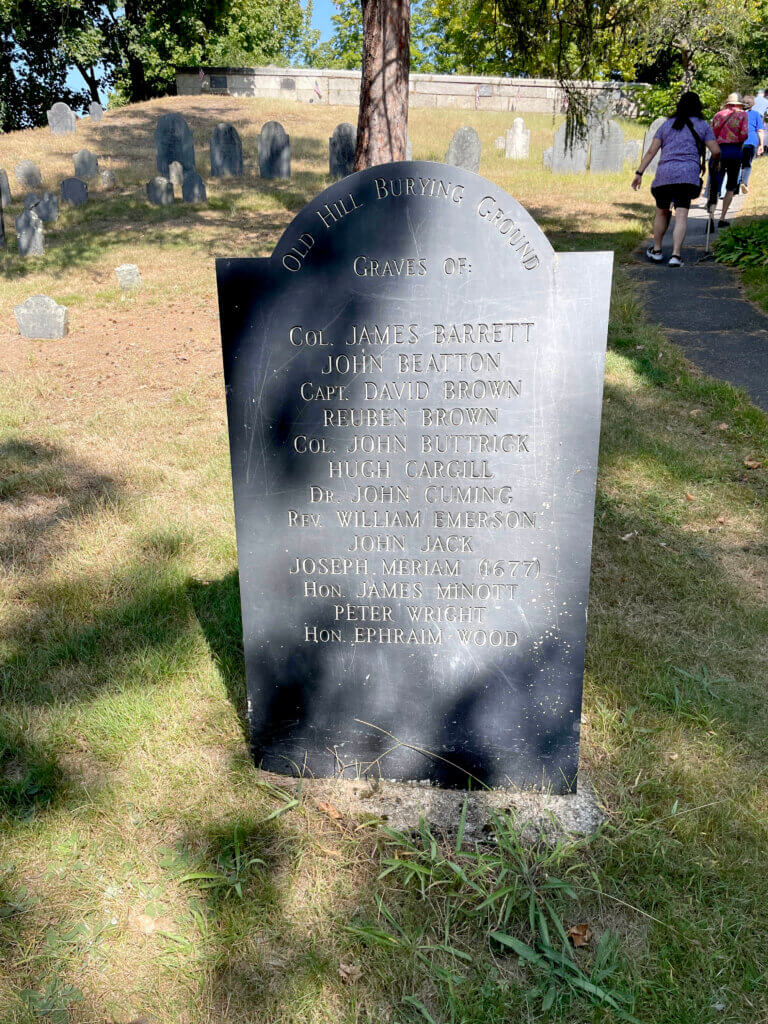

Old Hill Burying Ground

The walk stopped at Old Hill Burying Ground, which may have been constructed, Driscoll said, out of superstition. At that time, it was across the brook from South Burying Ground.

“In the 1600s and 1700s, there was a myth that it was considered bad luck if you were carrying a body over water,” he said.

The burying ground is the final resting place of 500 Concordians, but Driscoll drew attention to John Jack’s 1773 marker.

Jack, an enslaved man, bought his freedom for 125 pounds, about $25,000 today. His 20-line epitaph was written by Daniel Bliss, a loyalist who left Concord in 1774 because his life was threatened.

It begins: “God wills us free; man wills us slaves. / I will as God wills; God’s will be done.”

Photo: Christine M. Quirk/The Concord Bridge

Abolitionists

In 1837, Concord women, including Mary Merritt Brooks, Lidian Emerson, and Susan Garrison — Ellen Garrison’s mother — formed The Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society.

“The men came along later,” Driscoll said.

Those men included Henry David Thoreau, who, in July 1846, made a trip into town from Walden Pond. He was stopped by local jailer Sam Staples because he hadn’t paid his poll tax.

“He said he was not going to pay a tax to a government that allowed slavery,” Driscoll said.

Thoreau’s subsequent night in jail inspired his essay “Civil Disobedience.”

“Concord was a hotbed for the abolitionist movement,” according to Driscoll. Noted visiting speakers included William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, and Frederick Douglass.

Honoring the war dead

Driscoll said 49 Concord men died in the Civil War, but one soldier is missing from the memorial in Monument Square.

George Washington Dugan joined the 54th Massachusetts, the Black regiment immortalized in the movie “Glory.” Though he was killed on July 18, 1863, he was listed as missing in action on the monument dedicated in 1867.

Dugan, whose classification was amended to killed in action, was honored in 2023 with a monument and the full honors of a military funeral.

French, of course, designed the Minute Man statue at the North Bridge and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. His “Mourning Victory” figure is the center of the Melvin Memorial, which was installed in 1908 at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.