In 1971, when hundreds of protesters gathered in Concord, the country was in turmoil. Young people led protests against America’s involvement in Vietnam and the draft and their actions grew increasingly visible. The ranks of demonstrators grew.

Violence, at home and in Southeast Asia, drew attention from the media.

Three years earlier, National Guardsmen shot and killed four students and wounded another nine at Kent State University in Ohio, bringing an anti-war demonstration to a bloody stop.

During the My Lai massacre in 1968, U.S. soldiers slaughtered between 300 to 400 unarmed Vietnamese villagers in four hours and set fire to the buildings. Soldiers raped and mutilated women and girls.

America did not learn of the horror for more than a year and a half. Only one officer was convicted in a court martial which concluded in March 1971. No one was tried for sex crimes.

Vietnam veterans returned home to a country where it seemed no one wanted to know what they went through. They were isolated from their soldier brethren and knew their country had done wrong in the war.

The parades and celebrations held for their fathers returning from World War 2 did not happen for these young men who were injured in body and soul.

For the first time ever, American veterans protested the same war they fought in, said author and Lincoln native Elise Lemire, professor of literature at Purchase College, State University of New York.

While researching her 2021 book, “Battle Green Vietnam,” about the march organized by the Vietnam Veterans Against the War that began in Concord on Memorial Day weekend in 1971, she interviewed more than 100 participants. Thanks to the Lexington Library’s Oral History Project, Lemire had lots of information at her disposal.

VVAW was already known to the country. In April 1971, protesting veterans occupied the National Mall in Washington. They and their supporters attended hearings, demonstrated at Arlington National Cemetery and threw their medals onto the steps of the Capital.

The next month, VVAW organized a march based on Paul Revere’s ride as depicted by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The plan was to reverse the famous ride by marching from the Old North Bridge to Boston, visiting four Revolutionary War battlefields along the way: Concord, The Battle Road, Lexington and Charlestown.

Longfellow took liberties with the truth, Lemire pointed out. Revere never made it to Concord on the eve of the Revolution.

The 1971 protest was meant to show reverence for history while reminding the country of the ideals it once stood for, she said. Also, visiting the historical battlefields was part of a healing process for the veterans.

On the first three-day Memorial Day weekend in the country, the veterans began their journey from Concord.

“Concord embraced them at every turn,” Lemire said. Townspeople fed the men dinner and breakfast, sharing their grief as they walked through the battlefields of an earlier generation.

The veterans’ reception in Lexington was not as welcoming. Refused permission to camp on the green, the group attempted to set up anyway.

Well over 400 veterans and their supporters, including future Senator and U.S. Special Envoy for Climate John Kerry, were arrested and put in the Lexington Public Works building for the night.

The next morning, a Sunday, they were bused to Concord to appear in Middlesex District Court. Court convened on Sunday because Lexington could not accommodate everyone who was arrested, Lemire said.

The men held their arms behind their heads, symbolizing the prisoners of war in Vietnam, she said.

Concord came to the rescue of these 20th-century patriots, paying the $5 fine each was assessed, she learned.

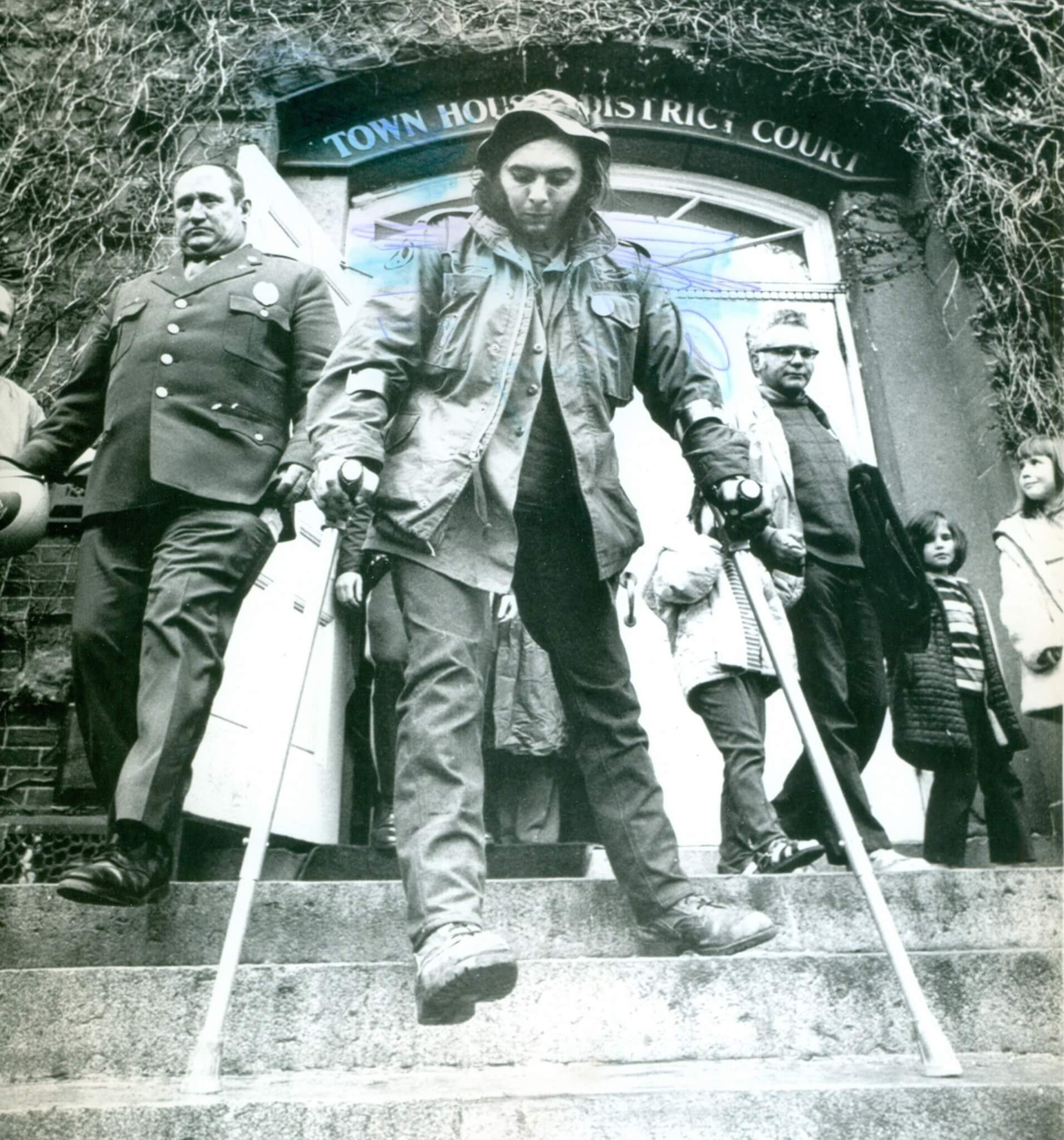

Images distributed by the media were a powerful tool for the movement. Phillip Lavoie, a veteran with two prosthetic legs, was photographed using crutches to descend the front stairs of the court at the Town House.

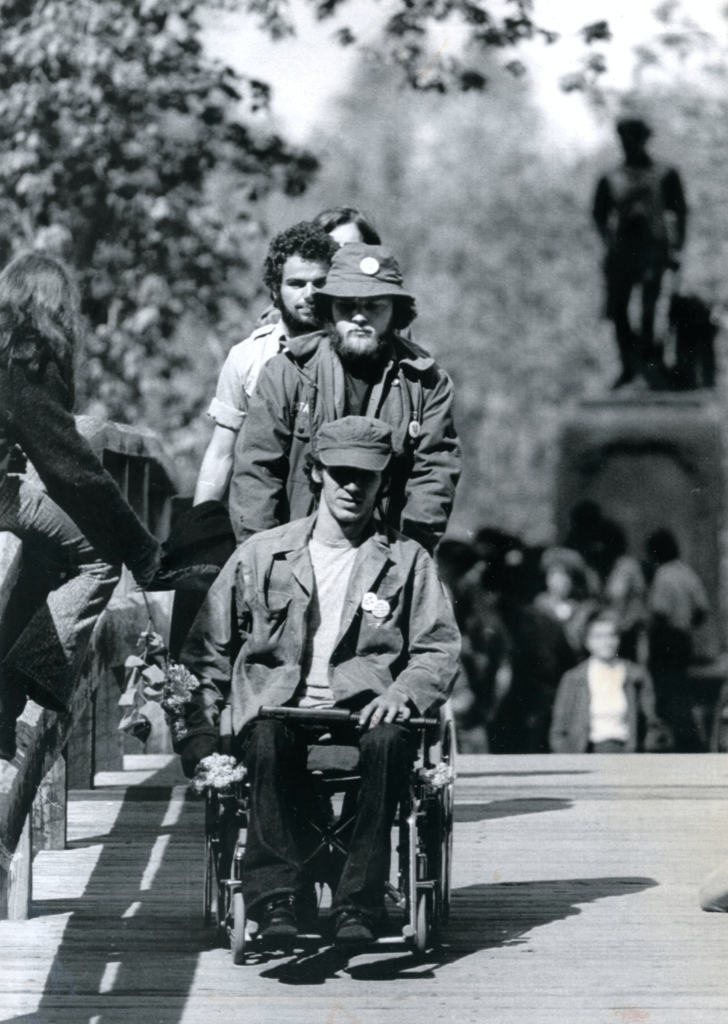

The photograph of another veteran crossing the Old North Bridge in a wheelchair was also featured by many news outlets.

Three other veterans, organizer Bestor Cram, Christopher Gregory and Lenny Rotman, will be part of a panel moderated by Lemire that “will explore the role of memorialized battlefields, the principles of civil disobedience, and the role protest can play in healing moral injuries.”

The country was founded on protest, wrote Joe Palumbo, Concord 250th events chair, in an email.

“We want to show that the celebration is more than just that moment in time, but we are celebrating the 250 years of progress we’ve made as a nation to expand freedom, liberty and equality and that work will continue in the years ahead,” he wrote.

“It’s an opportunity to meet some real heroes and learn about how the town assisted them in their endeavor,” Lemire said.

Sponsored by the Concord 250th Committee, the discussion will be held at the Goodwin Forum at the Concord Free Public Library at 129 Main Street, Sunday, November 5, from 2-4 p.m.

Reservations can be made on the library website concordlibrary.org.