After an unusually heated debate, the Select Board voted to cover up three nearly 100-year-old historical markers, deeming them offensive to Indigenous people.

In 1930, the Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentenary Commission distributed 275 cast-iron markers around the Commonwealth to mark the 300th anniversary of the colony’s founding.

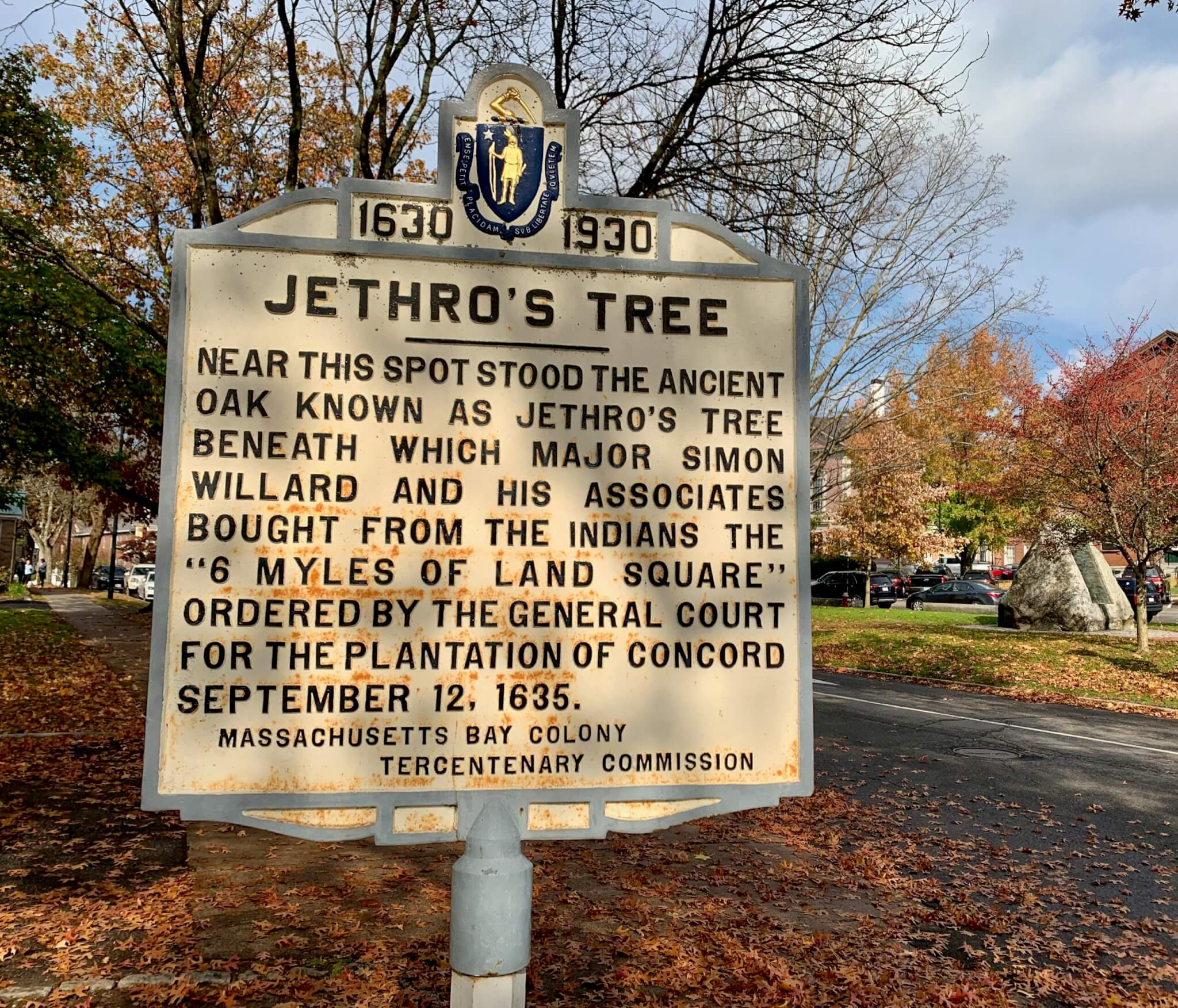

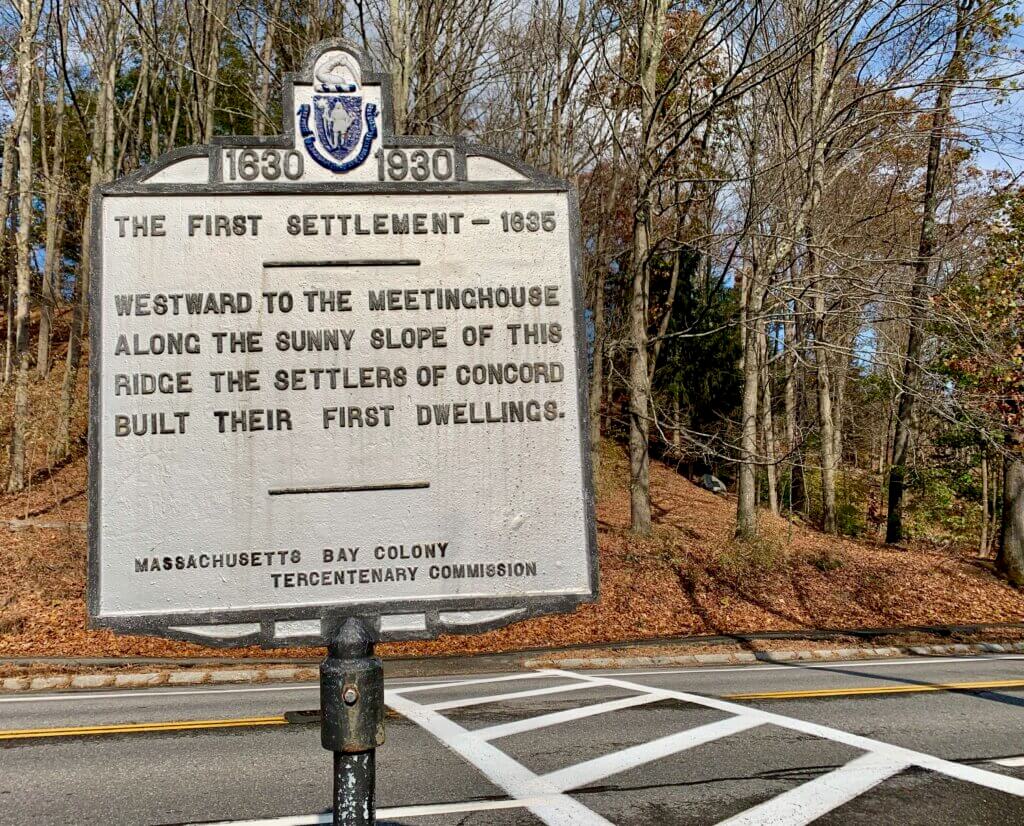

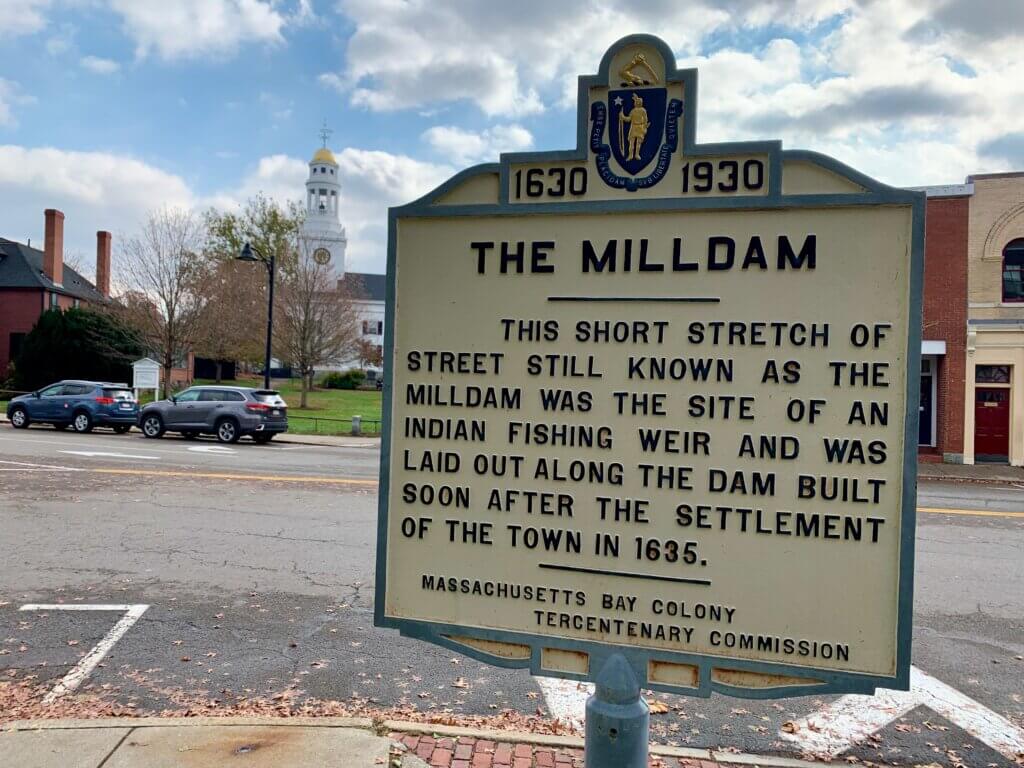

Three remain in Concord, and members of the town’s Historical and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committees argued that those markers — “Jethro’s Tree” and “The Milldam,” both in Monument Square, and a “First Settlement” sign near Orchard House — are historically inaccurate and objectionable.

The wording of three historical markers placed 100 years ago contains historical inaccuracies and objectionable wording, the Select Board was told. Photo by Jennifer Lord Paluzzi

“There’s Indigenous scholars who’ve told us these things need to come down,” DEI Commission Co-Chair Joe Palumbo told the Select Board, adding that the town had received at least one recent complaint from a visitor.

“I guarantee you, if we had a sign in town today across the street that said, ‘Enslavement taught many people good skills that they used later in life,’ [we’d] be taking that down by tomorrow morning,” Palumbo said.

Added DEI Co-Chair Andrea Foncerrada, “I think it is very brave [to say] our community today might not need what we needed a hundred years ago. Today, we can acknowledge we might be wrong, we might be offending somebody, and we can talk about it.”

Nancy Fresella-Lee of the Historical Commission, who’s been researching the markers since January, said they fail to acknowledge Indigenous people lived on the land now called Concord for thousands of years before English immigrants arrived and also feature the Massachusetts seal, which has been decried as racist and is undergoing a redesign.

“We already know [the signs] are problematic. They are historical. Some people like them because they’re historical objects — but they’re not works of art,” Fresella-Lee told the Board. “Their intention is to convey educational information, [but] they’re no longer educational. In fact, they’re offensive.”

Mark Howell, Select Board liaison to the DEI Commission, said there’s “good reason to believe [the markers] represent an ongoing harm to — and certainly an offense to — people visiting our community. And I believe that we should be taking some action to at [least] triage that issue immediately.”

He moved to cover the three signs “as soon as possible.” After consultation with the Historical and DEI Commissions, he said, options might include removing the markers, replacing them with “more accurate, relevant content” or working them into an “appropriate” educational exhibit.

But “by letting the status quo exist, we are passively accepting these narratives. And frankly, they’re almost slurs in some of the language that’s on these signs,” Howell said. “We really do need to move with some haste to mitigate that.”

Board Chair Henry Dane objected that he’d “been advised by historians that we should not take any action before we consult Native American consultants” on the subject. He raised the possibility that the Board could “designate a committee [to] advise us on the technical and linguistic and social issues.”

Voting on the markers Monday “was not on the agenda. People who had other points of view about this issue [didn’t] have the opportunity to come and speak about it,” Dane argued.

“Those signs have been there for a hundred years,” he said, “and whatever harm has been done, it’s not going to be materially changed by having us make an informed decision about what to do.”

In fact, the signage issue was on the original agenda made public for Monday’s meeting. Dane confirmed he had asked that it be removed for more study.

Palumbo told Dane that the issue had been on the table for a long time, there was no reason for further delay, and said “one of our jobs is to push you. It’s our job as the DEI commission to [talk] about these things… We’re happy to work with you on it — but it was taken off the agenda and it wasn’t put on another agenda. So we’re sort of lost.”

Board members Howell, Terri Ackerman and Mary Hartman voted in favor of covering the signs. Dane dissented, “not because I’m necessarily opposed to this, but I think we are not being deliberate and we’re not considering the larger issues involved here.” Select Board member Linda Escobedo was not present.

The 1930 signs were intentionally designed with text big and clear enough to be read from passing cars. Nearly 100 years later, as the Gloucester Daily Times has reported, many have vanished from their original spots. Some were tracked to municipal storage or historical societies. At least one was reportedly spotted at a junkyard.

Concord’s Monument Square signs were restored about a decade ago. The town originally had four signs, according to Fresella-Lee: The marker labeled “Musketaquid-Concord,” posted on the Lincoln border, disappeared long ago.

After the meeting, Howell said he hoped the cloaking the markers would spark a meaningful conversation about the town’s history. Separately, Dane said he wished the board had considered the matter more thoroughly before acting, rather than giving in to “pressure.”

For his part, Palumbo said he and his colleagues “were heartened to see three Select Board members show leadership [to] move this forward and take concrete steps to make Concord more welcoming to all people.”