By Erin Tiernan — Erin@theconcordbridge.org

Some Concordians say they’re skeptical a Superfund site in town will ever be safe enough to build homes — despite an exhaustive, decades-long cleanup of the land.

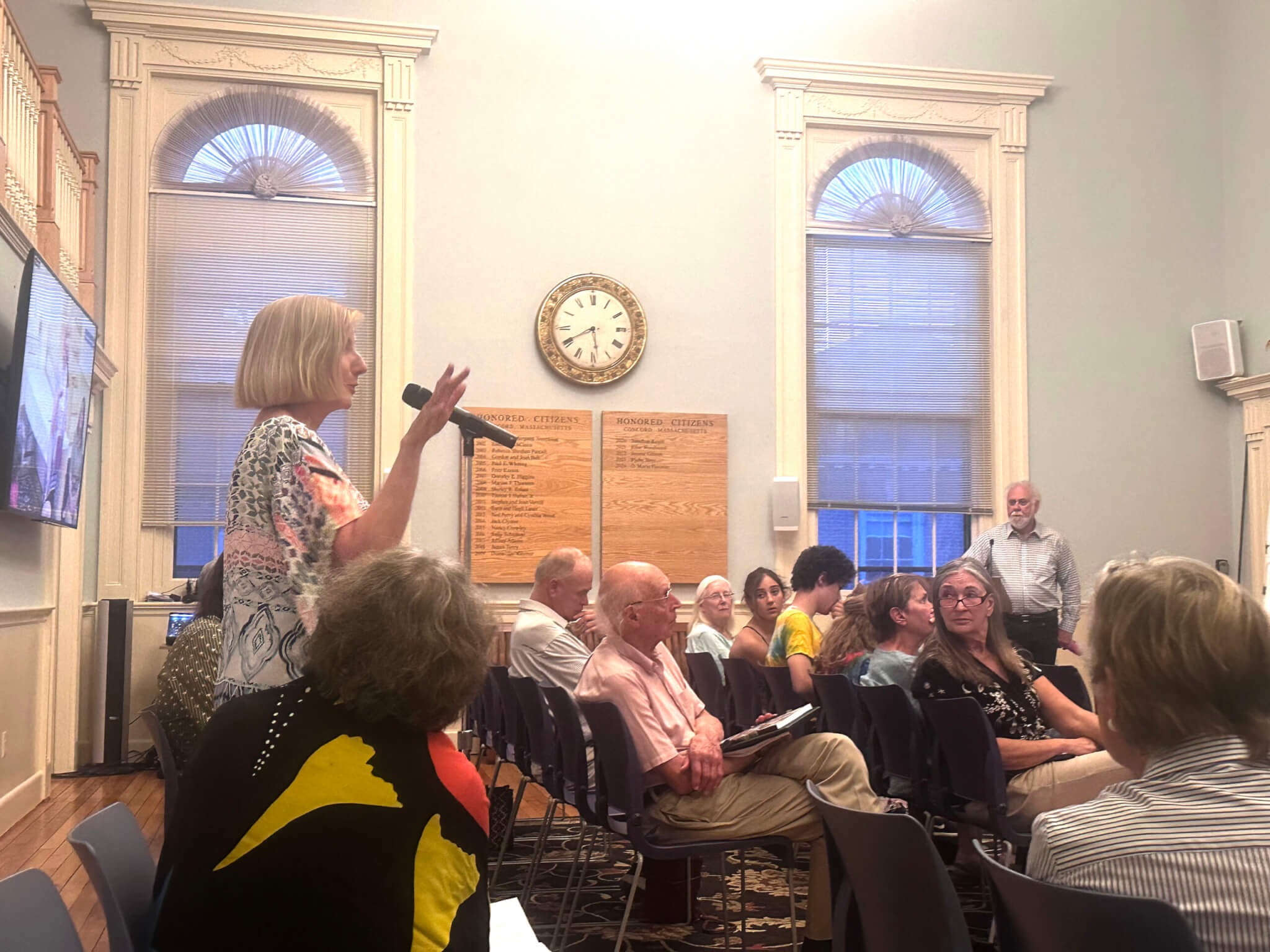

Residents’ desire to see the property put to use came coupled with questions about long-term health risks and potential liability issues for the town at a public hearing on June 4.

“Who would intentionally move into a place where there was a toxic waste site?” asked Michael Amster of Prairie Street.

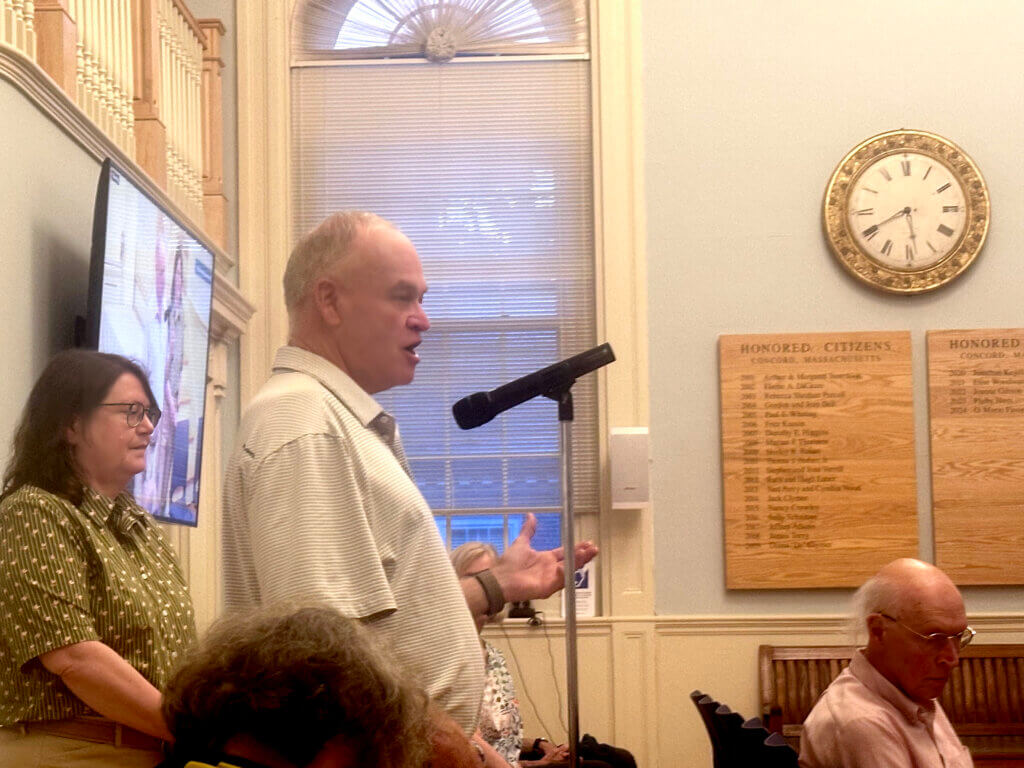

Members of a town task force charged with recommending whether Concord should take ownership of 2229 Main Street said public perception around risk potential will play into the appetite for redeveloping the site and is an important part of their analysis.

Future concerns

Questions like Amster’s hit close to home for Janet Benvenuti of Jonas Brown Circle. Benvenuti, a nuclear chemist, said she grew up in Woburn, where pollution from an industrial site leached into the drinking water and was later linked to a leukemia cluster and other adverse health consequences.

Benvenuti said she’s concerned waste that will be encapsulated at Concord’s Nuclear Metals Inc. site will cause harm down the line. She doesn’t want the town on the hook.

“My concern is for future liability,” Benvenuti said, noting the holding basin on the property that was capped to seal in toxic waste is not entirely impermeable.

“We’re going to have to monitor the water that’s migrating over from that. And I guess the question is, how can we factor that into the costs for the future?” she asked.

Task Force Chair Paul Boehm said the risk is low and is only to deep groundwater — not the town’s drinking water. He noted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is overseeing the cleanup, will monitor the site “in perpetuity.”

Concord would not be held liable for consequences of pollution from historic operations on the site, Boehm said.

Heavy metals and housing

The EPA says the land at 2229 Main is being decontaminated to its highest standard — “residential use” — which allows for almost any type of activity on the site, including housing.

“Part of me is a little skeptical about how well it will be cleaned, how safe it will be,” said Frederick Oleson, who holds a Harvard doctorate in radiation oncology. He said he’s particularly concerned about heavy metals on the site and how exposure could affect young children and people with genetic conditions.

Part of the task force’s job, member David Ropeik said, will be to “build trust” with residents and convince them that the science behind the cleanup is sound.

Decontamination of the 46-acre site has been ongoing to various degrees since 1980, when chemical pollution from depleted uranium, beryllium, 1,4-dioxane, and other hazardous chemicals became evident in the soil and groundwater and the state Department of Environmental Protection ordered a cleanup.

More than 115,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil and sediment have been removed, and topsoil has been replaced to a depth of 10 feet. Following the installation of a permanent groundwater treatment facility, critical groundwater extraction and purification to protect Acton’s water supply from pollutants are ongoing.

Concordian Pam Rockwell, who serves on a separate town committee tasked with oversight of the same property, said the site would have controls in place to diminish future risk following redevelopment. Across the U.S., 452 of the more than 1,300 Superfund sites have been cleaned up and are now considered safe for redevelopment.

“There are certainly plenty of sites that have been cleaned up and used for residential areas that have similar risk to this,” Rockwell said.

The Woburn Industri-Plex property near where Benvenuti grew up is one of them. Restaurants and retailers moved in first and now the land also hosts luxury apartment buildings.

Housing is just one of many redevelopment opportunities that will be possible once the EPA declares its cleanup complete, likely in late 2028 or early 2029.

Weighing possibilities

The town’s 2229 Main Street Advisory Task Force is vetting the likely outcomes of four options as it considers its recommendation on what role, if any, the town should play in the redevelopment.

The town could acquire the land entirely for municipal purposes or to facilitate private development. The other two scenarios envision private ownership granting the town some access and another where the land is purchased solely for private development.

The task force’s report is due to the Select Board on October 31. It is also vetting a potential risk to human health once the land is put back into use, as well as legal liability, cost, and other details of transferring ownership.

There is one private lien on the property and a federal lien that’s expected to grow alongside project costs. The total price tag is projected to hit $300 million. The federal government is covering 98 percent of that cost, with responsible parties covering the rest.

Boehm said there have been “many eyes on the site” throughout the cleanup and it’s in the interest of taxpayers to get the land back into safe use.

“Even though we pushed hard to get this done up to residential standards, I’m a little skeptical that this is going to be safe enough for all potential uses, particularly different age groups, younger children, babies,” Oleson said.

Boehm said all the science and intensive soil sampling so far points to low risk for cancer or other health impacts for all possible uses.

The task force has contracted third-party consultant Roux to evaluate risk potential. Boehm said “that work is just beginning,” but in a preview of their findings last month, scientists said the increased risk of cancer from living on the site was one in 1 million — well within federal “acceptable” risk standards.

“Ultimately, the people — we, us, the government — [have] to pay to clean this up,” Amster said. “Whatever we do here, we need to make sure whoever is overseeing what is going on, or what should be going on, is held accountable.”

Editor’s Note: A version of this story which appeared in the June 14 print edition of The Concord Bridge misattributed comments made by resident Pam Rockwell to a member of the 2229 Main Street Task Force. This version of the story has been updated. The Bridge regrets the error.