By Laurie O’Neill — Laurie@concordbridge.com

Who or what determines whose faces become a part of history? And why can portraits be so moving or evocative even when a viewer does not know the subject’s name or the reason for the image?

The Concord Museum is inviting visitors to consider these questions with a special showcase of portraiture in its many forms.

Titled “Portrait Mode,” the exhibit opened this month and runs through February 23.

Time-consuming and expensive, portraiture in oils was once largely reserved for the wealthy, but capturing likenesses became significantly more accessible due to technological innovations in the 19th century. These include silhouettes and ambrotypes (photographs on glass).

The Museum is exhibiting more than 40 historical portraits from its collection that represent a range of formats, from tiny photos preserved in lockets to miniature tintype albums, silhouettes, oil paintings, and sculpture.

Though their subjects may have faded into obscurity, they can still speak to us of the times in which they lived.

Lives behind the images

The pieces “offer powerful glimpses of how portraits were used as tools of memory making,” says Museum Executive Director Lisa Krassner. They reflect “the ways people used these technologies to preserve the memories of their loved ones, something that we take for granted today.”

Associate Curator and Director of Exhibitions Reed Gochberg says, “As much as these portraits preserve individual lives, they also point to larger questions of representation and absence — who we remember through portraiture and whose faces remain just outside of the frame.”

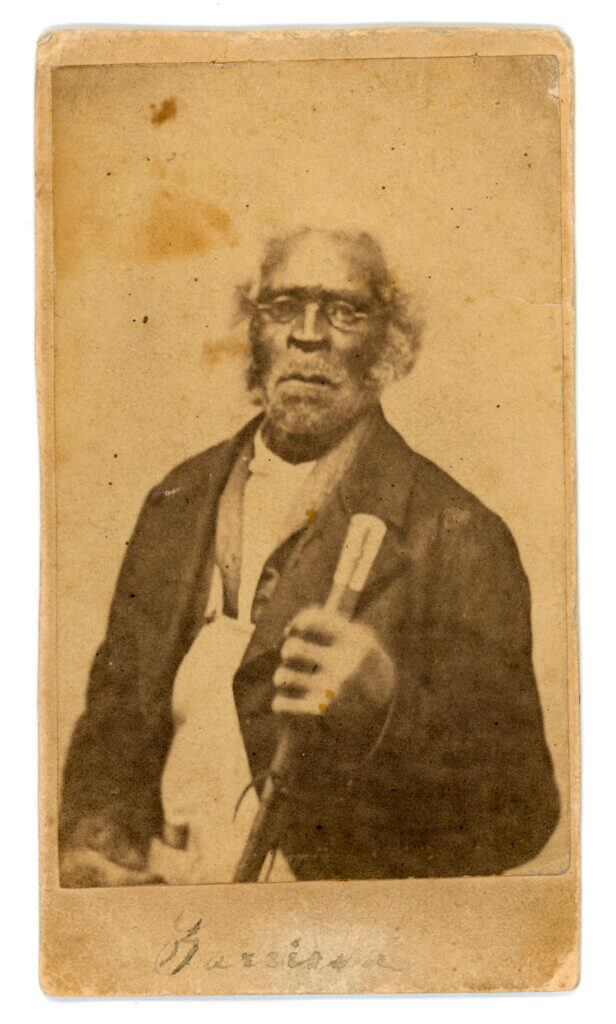

Featured objects include a carte de visite (a small portrait mounted on a card) of Jack Garrison, who escaped slavery and settled in Concord. He raised a family that included Ellen Garrison, an African American educator, abolitionist, and early Civil Rights activist.

There is a posthumous portrait of Union Army Cpl. William Johnson Damon, son of Edward Calvin Damon of the Damon Textile Mill, which produced cloth for Union Army uniforms. William died at 21, and his name appears on the 1867 Civil War memorial in Concord Center.

There is also an image of Alicia Keyes (though it is inscribed “Miss Elisha Keyes”), a celebrated Concord artist who was the daughter of John Shepard Keyes, a lawyer and U.S. marshal for Massachusetts.

“Portrait Mode” brings into focus the ways that information has been lost over time, says Krassner. “Though the identifying information may be missing, these portraits are still powerfully evocative representations of the life behind each image,” she adds.

The Museum, at 53 Cambridge Turnpike, is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and on Monday holidays. For more information, go to concordmuseum.org.