By Erin Tiernan — Erin@concordbridge.org

The fate of a residential tax exemption intended to make Concord more affordable is in the hands of the Select Board, which will vote next month whether to quash the measure or keep it in place for a second year

The policy that shifts the tax burden from lower-value, owner-occupied houses onto higher-value homes and rental properties is one of a “limited number” of tools available to officials trying to make the tax structure fairer, Select Board chair Mary Hartman told The Concord Bridge.

“The RTE advances our goals of diversity and inclusivity by enabling residents to age in their homes, by allowing people with different levels of wealth to move in or continue to live in our town, and promoting more heterogeneity in our housing stock,” Hartman said at a Monday night forum soliciting feedback ahead of next month’s vote.

Catching a break

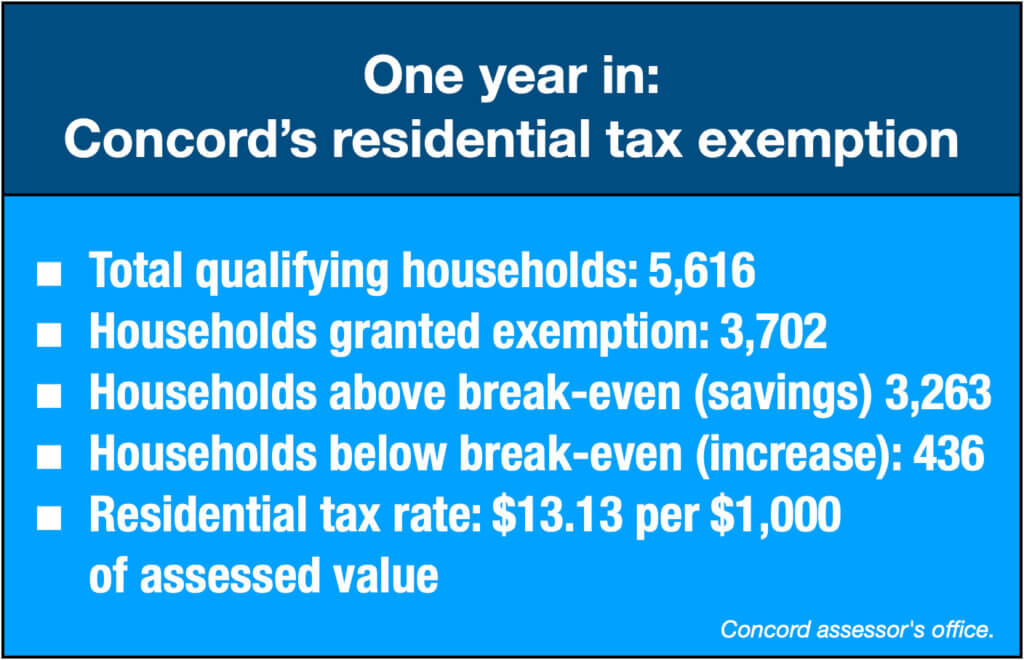

In its first year, 3,702 households took advantage of the tax credit, which exempts 10 percent of the median value of a Concord home — about $143,000 — from the property values of qualifying homes before calculating tax bills.

“Many parcels saw a tax increase, because the tax rate increased,” town assessor Meredith Stone said. “Whether you were above or below the break-even point would determine if you would benefit or not from the residential exemption.”

Of the households who received the exemption, 88 percent were valued below the break-even point of $2.1 million and saw a tax break. The cut for some households was effectively subsidized by commercial and rental properties and the other 12 percent of high-value homes, whose owners paid more.

Supporters like Richard Loynd, whose family has lived on Crest Street for 90 years, say it’s a progressive measure that helps some fixed-income seniors and lower-income families stay in Concord despite rising tax bills compounded by skyrocketing home values.

“I know people in West Concord who fear they’re going to have to go to a blood bank to pay their next tax bill,” said Loynd.

Critics, however, point out that the policy can actually hurt seniors with high-value homes while handing out breaks to residents who may not need it.

Needs review

Concordians continued to split their support for the tax plan, but neighbors on both sides found common ground in their desire for more analyses of its impact.

“There is zero data to show that the RTE has made Concord more affordable,” said Mark Martines of Alford Circle, who opposes the policy.

Speaking in favor, Pamela Dritt of Concord Greene urged town officials to “please do the analysis” but told her neighbors, “there is not going to be anything that’s considered fair by everyone.”

“We want diversity, and that means we have to help people who don’t have the economic means to live here,” Dritt said.

Joseph Laurin of Southfield Road talked about a “common theme” of wanting to help neighbors “who cannot afford ever-increasing taxes.”

“We need something that’s more refined that actually takes into account someone’s ability to pay, not just based on the value of their home.”

‘Economic divisiveness’

Susan Bates of Concord Greene urged town officials to acknowledge the “elephant in the room,” which she used as a metaphor for town debt and paying for voter-approved capital projects like the new middle school. That debt will hit the tax rolls in 2026 with a price tag of more than $100 million.

Elizabeth More of Blueberry Lane said she’s “morally opposed” to the policy even though her family benefitted from the exemption.

“It feels like we are robbing Peter to pay Paul,” she said. “It doesn’t target those in need, and it causes another form of economic divisiveness between neighbors.”

Mark Hill of Westford Road challenged town officials to attract business to Concord to raise revenues through a commercial tax base.

“The burden here is being decided by a finite pool; let’s not do that to ourselves,” Hill said.

Concord relies heavily on residential property owners, who make up 93 percent of the town’s tax base, to cover town costs.