By Dakota Antelman — Correspondent

Just under a year after the Select Board voted to remove a trio of controversial tercentenary markers in Concord, the future of the cast iron signs remains unclear.

As community members pitch ideas, many say the markers should end up in a museum. But the list of possible destinations includes multiple options. And for some, whatever happens next should go far beyond the signs themselves.

“This town has a long way to go,” said Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Commission member Jimi Two Feathers. “So, taking down the signs is only one little piece of it.”

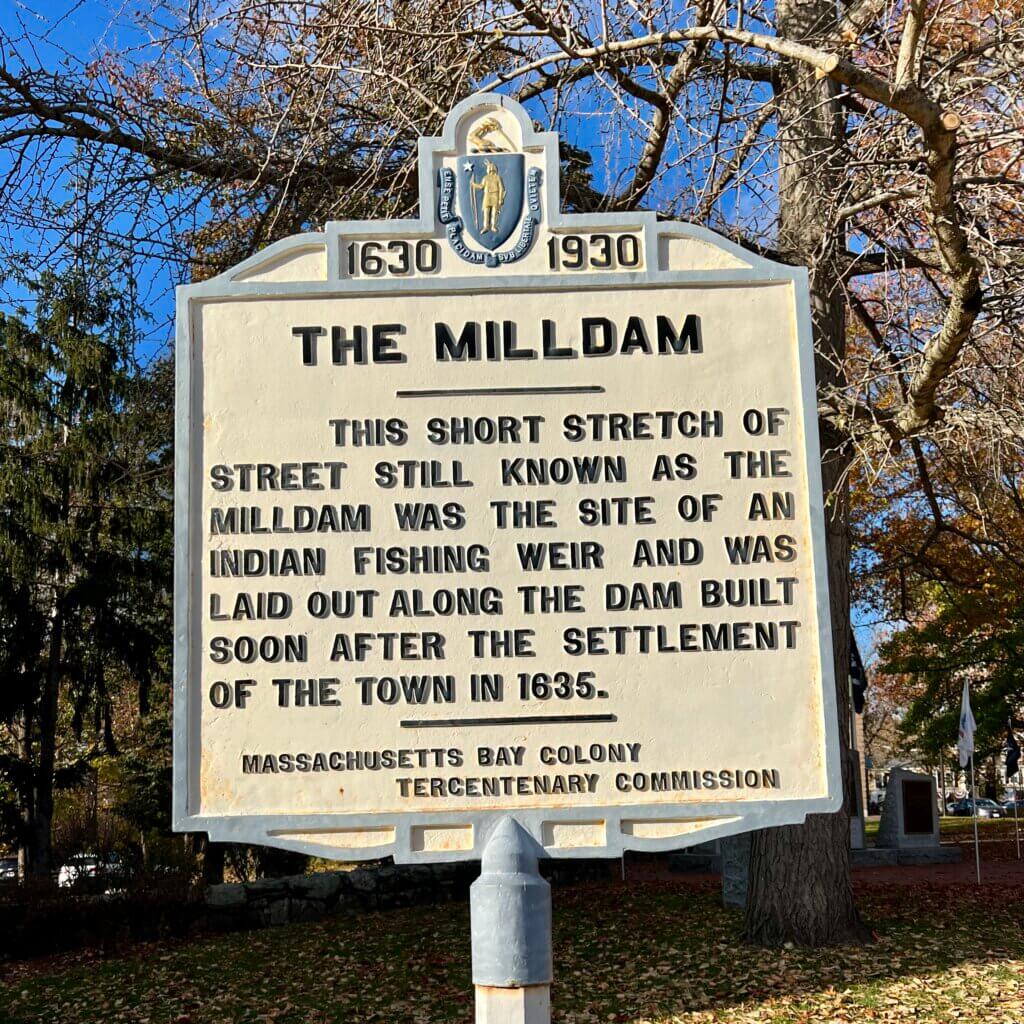

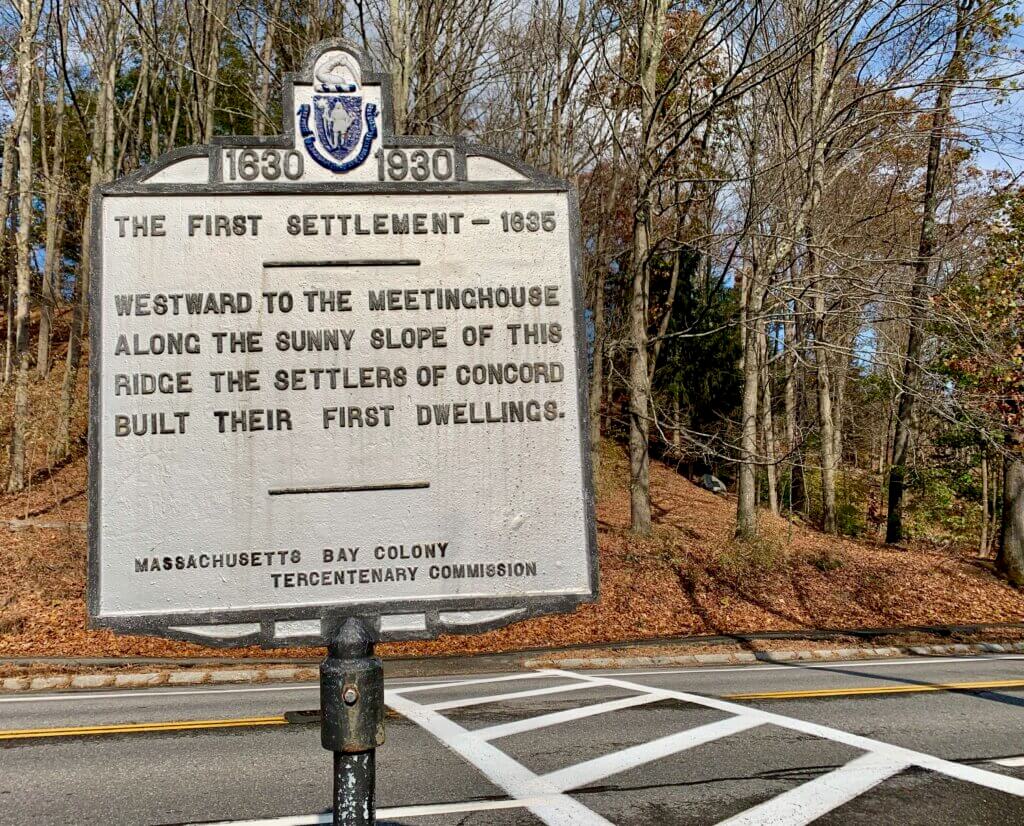

Photo: Celeste Katz Marston/The Concord Bridge

The tercentenary markers date back to 1930 when the state installed 275 informational signs for the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Some markers were forgotten or went missing over the years. Within Concord, three markers still stood when DEI and Historical Commission members argued they were offensive to Indigenous people and historically inaccurate in their portrayal of the relationship between colonists and Indigenous communities.

Removed last January

In November, the Select Board voted to remove the signs “for maintenance.” The markers came down in January and went into storage, according to Select Board clerk Mark Howell.

On the eve of Indigenous Peoples Day, with questions about the signs’ future unanswered, several board and commission members say they want to see the markers displayed at a facility such as the Concord Museum — with context explaining the signs’ history and correcting inaccuracies.

Jim Sherblom, a Concord resident and an author who has studied local indigenous history, mentioned the Town House and the Concord Sign Museum as other candidates.

Katy Morris, the Concord Museum’s director of marketing, communications, and media relations, said the town has not approached the museum about the markers.

“Any decision to accession the markers into the museum collection would be made after careful consideration in partnership with the town, our collections committee, as well as our close partnerships with Indigenous advisors,” she said in a statement.

Context is key

Like Morris, Sign Museum co-founder John Boynton said there has been no conversation with the town about displaying the markers.

“[I]t may be worth exploring, provided we could interpret [the markers] appropriately,” he said.

Town communications manager Donna McIntosh said in January that the chairs of the Historical and DEI Commissions were “invited to begin a conversation to discuss the interpretation and messaging on these sites, as well as a plan for the actual signs.”

A meeting on the topic got canceled due to a schedule conflict and has not been rescheduled, according to DEI Commission co-chair Joe Palumbo.

McIntosh acknowledged the meeting cancellation but said the Historical Commission could still make a recommendation for their future disposition, including relocating the signs to the Concord Museum, the Concord Sign Museum, “or another appropriate institution.”

“Additionally, the commission could explore opportunities for future signage, interpretive information, or educational programs to illuminate the history of these markers and their original locations,” McIntosh said in an email to The Concord Bridge.

McIntosh said the signs remain in secure storage but declined to provide specific details.

‘Overdue in reaching out’

Historical Commission member Nancy Fresella-Lee advocated to remove the signs. Now, she says she’s concerned they will be forgotten or lost.

Fresella-Lee said she thinks town staff is “overdue in reaching out to the Concord Museum about the future of the markers.”

And Howell said he hopes the Historical Commission will work with the DEI Commission to “frame this in a way that allows us to really be deliberate about what to do.”

“We shouldn’t let this completely fall off the table and not get addressed,” Howell said.

Meanwhile, asked about the markers, Tara Mayes, who manages communication for the Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band, told The Bridge that members of the Band are “working with the Historical Commission of Concord to discuss future engagements and ongoing conversations with the Nipmuc people and Concord.”

A chance for ‘teaching lessons’

Two Feathers, who’s of African American, white, and Wampanoag descent, said he hopes to see more education about Indigenous communities in the Concord area.

Others agreed, proposing options ranging from panels on Concord’s Indigenous history to new markers that help visitors learn about actual interactions between colonists and Indigenous people.

Two Feathers said Concord should use “teaching lessons” to confront ugly elements of its past. An exhibition explaining the story behind the tercentenary signs — and their removal — could be one such educational moment.

“I think it would be a really good thing if it was in a museum, as long as the history [is there showing] what it was and why it was taken down,” Two Feathers said of the signs.

“… Every opportunity like this should be [an] opportunity for people who want to look behind the cover a little bit.”